Making Headlines

For a printable version of this article, please click here.

Did you know…

Did you know…

America has a long history of the importance of newspapers and journalism. Codified in our Constitution in the First Amendment, freedom of the press was important to our nation’s founders. But even though some newspapers predate our nation’s independence, like Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette, it would take another 51 years until a newspaper was owned and operated by a person of color.

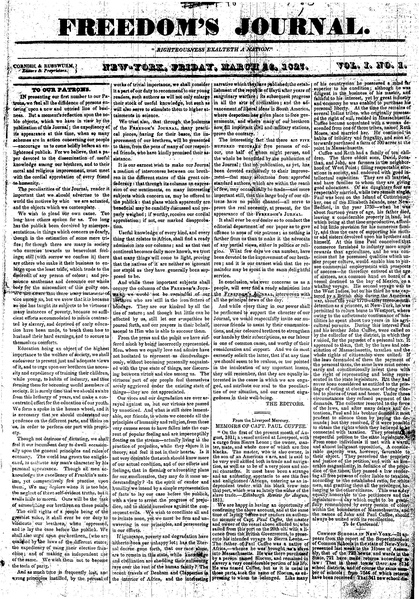

“We wish to plead our own cause. Too long have others spoken for us…” With those words, the first Black-owned and operated newspaper was printed on March 16, 1827. Freedom’s Journal, as it was named, was established by Samuel Cornish, an abolitionist, preacher, and a New Yorker by birth, and John B. Russwurm, born to an enslaved Jamaican woman, he was the first person of color to receive a degree from an American college. In their paper, Cornish and Russworm confronted slavery, lynching, and other oppressive practices. But they also strived to create a sense of fellowship amongst the Black community with their paper, giving voice to the opinions and everyday lives of Black people, including listing their births, marriages, and deaths, which couldn’t be found in white-owned and operated newspapers.

Freedom’s Journal closed after 2 years of publication, but it inspired the establishment of over 40 Black-owned and operated newspapers in the northern US by 1860 (there was no Black press in the southern US until during and after the Civil War). The great orator and abolitionist Frederick Douglass was the owner of two such papers – The North Star (1847-1851), whose title referred to the actual North Star, Polaris, that helped guide people escaping slavery to safety in the North; and Frederick Douglass’ Paper (1851-1860). He also owned a third paper after the war, called the New National Era (1870-1874), that promoted Reconstruction and denounced racism and violence towards African Americans, which was increasing due to the rise of the Ku Klux Klan.

-

Ida B. Wells – Pioneering Journalist

Warning: This part of the article talks about racist violence and lynching.

“The facts have been so distorted that people in the north and elsewhere don’t realize the extent of lynchings in the south.”

Ida B. Wells was born into slavery in Holly Springs, MS, in 1862, and fought against discrimination and injustice for most of her life. As a young women living in Tennessee, she was asked to move to a segregated railroad car, and was forcibly removed when she refused to do so. She sued the railroad company successfully at the local level, but the suit was overturned by the Tennessee Supreme Court. As a teacher, Wells was fired by the school board when she spoke out about racism and the poor conditions of Black schools in Memphis. Turning to journalism, she owned and edited The Memphis Free Press & Headlight, fearlessly investigating and reporting on the brutal lynchings of Black men in the South. A local mob then burned down the paper’s offices and drove Wells and her family out of Tennessee with death threats. Undaunted, she wrote for several newspapers in the North, including The New York Age, and Chicago newspapers The Conservator and the Daily Inter-Ocean, and was an editor for The Chicago Bee. Outside of journalism, Wells toured Europe, speaking to international audiences about the evils of lynchings in the US, and brought her anti-lynching campaign to the White House in 1898. She fought for suffrage for women, and for civil rights for African Americans, helping found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Ida B. Wells died on March 25, 1931.

Ida B. Wells was born into slavery in Holly Springs, MS, in 1862, and fought against discrimination and injustice for most of her life. As a young women living in Tennessee, she was asked to move to a segregated railroad car, and was forcibly removed when she refused to do so. She sued the railroad company successfully at the local level, but the suit was overturned by the Tennessee Supreme Court. As a teacher, Wells was fired by the school board when she spoke out about racism and the poor conditions of Black schools in Memphis. Turning to journalism, she owned and edited The Memphis Free Press & Headlight, fearlessly investigating and reporting on the brutal lynchings of Black men in the South. A local mob then burned down the paper’s offices and drove Wells and her family out of Tennessee with death threats. Undaunted, she wrote for several newspapers in the North, including The New York Age, and Chicago newspapers The Conservator and the Daily Inter-Ocean, and was an editor for The Chicago Bee. Outside of journalism, Wells toured Europe, speaking to international audiences about the evils of lynchings in the US, and brought her anti-lynching campaign to the White House in 1898. She fought for suffrage for women, and for civil rights for African Americans, helping found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Ida B. Wells died on March 25, 1931.In 2020, Wells was awarded a Pulitzer Prize, “For her outstanding and courageous reporting on the horrific and vicious violence against African Americans during the era of lynching.”

In 2022, Congress finally passed anti-lynching legislation with the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act, which re-defined hate crimes as any conspired offense that is motivated by bias, resulting in the death or severe bodily injury of the victim. It’s named after Emmett Till, a 14-year-old Black boy who was kidnapped, tortured, and murdered for the alleged “crime” of talking to a white woman.

Learn more about the amazing and courageous life of Ida B. Wells. Learn more about the tragically short and meaningful life of Emmett Till.

The end of the Civil War eventually saw emancipation of those who had been enslaved, and the failure of post-war Reconstruction began what is known as the Great Migration. During this time, over 6 million Black Americans moved from the Jim Crow South to the North, Midwest, and West, fleeing poverty, violence, and oppression. In these new places, they found what Cornish and Russworm decided decades earlier – that for the voices of the Black community to be heard in local newspapers, they had to print them themselves.

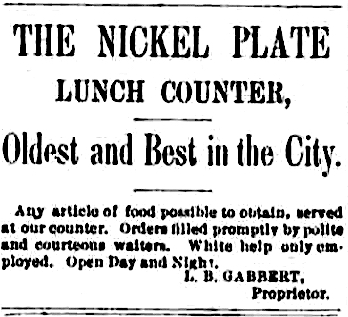

An ad from the January 2, 1892 issue of the Arizona Republican.

Late 19th century newspapers covered local, national, and world news and events, but also included a lot of local tidbits and gossip. We know Flora Murray and Roland Rosson attended a Golden Leaf Croquet Social Club outing because it was mentioned in the June 28, 1879 issue of The Phoenix Herald. We know that the Goldberg family owned a piano, and we know how much they paid for it – $650 – because the purchase was reported in the Arizona Republican on September 24, 1893. Papers at the time reported on society events, locals vacationing elsewhere and visits from friends and family. They also included ads from local businesses. However, the majority of white-owned newspapers didn’t mention the social or business lives of African Americans in their communities, and usually if they mentioned Black people or race at all, it was negatively.

Newspapers like The Philadelphia Tribune (1884-present), The Afro-American (1892-present, Baltimore), and The Chicago Defender (1905-present) and more were started by the Black community so their voices and their stories could be shared and heard. They covered national and world news along with local topics like Black home ownership, society, education, religion, businesses, and jobs, but also talked frankly about racial atrocities in the South. White newspaper distributors refused to carry The Chicago Defender in the South, so it had to be smuggled in via Pullman railroad porters, passing hand to hand or read in the safety of Black businesses. These newspapers were a substantial part of the Great Migration boom, giving Black people from the South information about economic opportunities elsewhere, along with hope for better lives.

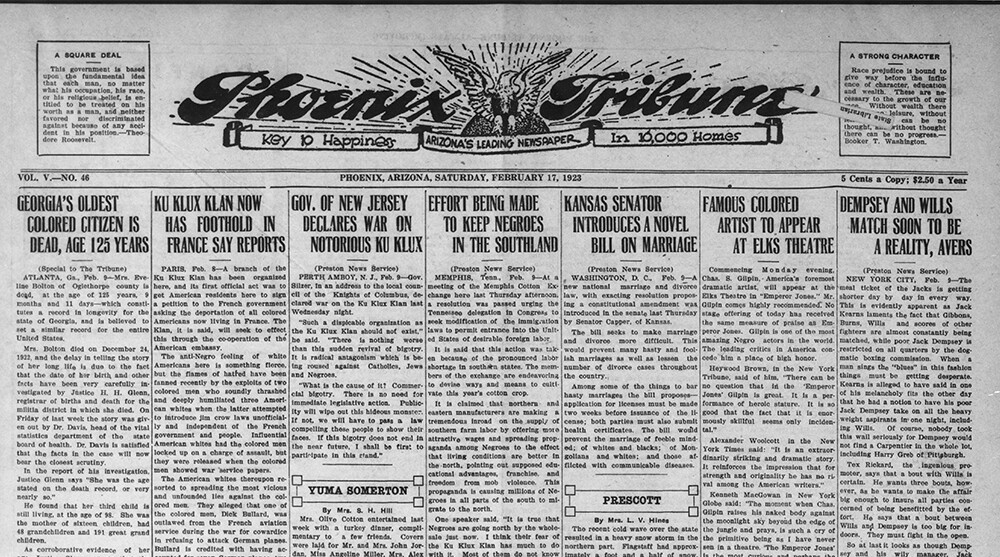

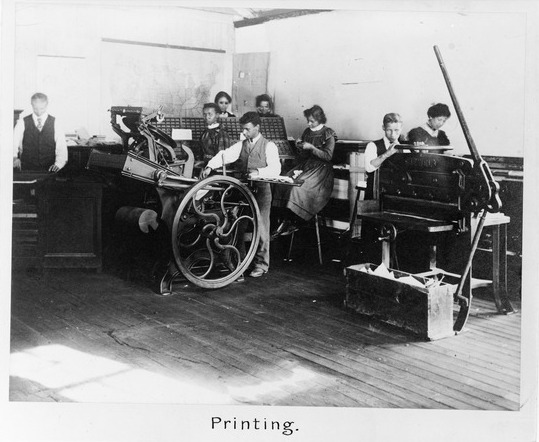

Arizona’s first Black owned and operated newspaper, the Phoenix Tribune was established in 1918 by Arthur Randolph Smith almost a century after Freedom’s Journal was published. And there was a need for it. The census shows that the African American population in Arizona had major growth at that time – quadrupling from 2,009 to 8,005 over the decade between 1910 to 1920. They were living in an Arizona that segregated schools in 1909 and outlawed interracial marriages in 1864. While not codified in the state constitution, segregation of Arizona communities and businesses was a terrible reality. The Phoenix Tribune published a supplement, called the Arizona American, that prompted readers to, “Spend your money where you are welcome!” Interestingly, the Tribune, with Smith as its editor and Helen Harper Vance as its assistant editor, was supported by the Arizona Republican (now the Arizona Republic), allowing Smith to publish the Tribune on their own printing press for a small fee, occasionally advertising for the Tribune in their own paper, and saying Smith’s work was “Miraculously clever, his paper neat and clean and we are glad to see it is well patronized by advertisers.” Arthur Smith would remain the paper’s editor until it closed in 1931.

A portrait of Ayra Hackett, circa 1929

There have been several other Black-owned and operated newspapers in Arizona since the Phoenix Tribune was established, including the Phoenix Sunday State (Phoenix, 1920s), The Western Dispatch (Phoenix, 1920s), The Arizona Times (Tucson, 1926-34), The Phoenix Index (Phoenix, 1937-1943), Arizona’s Negro Journal (Tucson, 1942-43), the Arizona Sun (1942-63), The Arizona Register (Tucson, 1946+), the Arizona Tribune (1958-73), the Arizona Black Dispatch (1976-77), the Phoenix Press Weekly (1970s+), the Arizona Now Newspaper (1974+), and the Arizona Informant (1971-present). There are a few, however, that we’d like to mention separately:

-

- The Arizona Gleam (Phoenix, 1929-3?) – Established in Phoenix by Ayra Hackett, this paper is unique in that it was the only newspaper in all of Arizona that was both owned and operated by a Black woman. Most of the staff of the newspaper were also women. An Arizona trailblazer, Ayra Hackett was married to a man who was another state pioneer – Dr. Winston Hackett, who was the first African American doctor in Arizona. The Arizona Gleam covered world, national, and local news, including updates about local schools, churches, youth activities, and a professional directory. It also spoke out against racism and promoted Black businesses and home ownership. Ayra Hackett was the newspaper’s editor until her sudden death in 1932 from pneumonia. She was 35. The paper continued without her into the late 1930s.

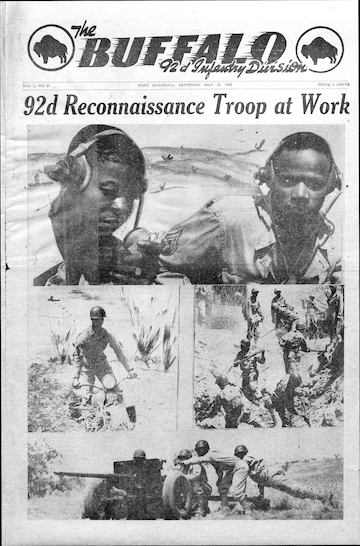

The Bullet (25th Infantry Regiment, 1928-1940s), the 93rd Blue Helmet (93rd Infantry Division, 1942-43), The Buffalo (92nd Infantry Division, 1943-45), The Apache Sentinel and it’s Postscripts (92nd Infantry Division, and the 32nd and 33rd companies of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps, 1943-45) – Each of these newspapers were published at Ft. Huachuca for segregated soldiers and members of the WAAC (later the Women’s Army Corps, or WAC) stationed there before and during World War II. Outside of talk about the war (when there was one), the papers talked about training, competitive sports (including info about the fort’s baseball team), soldiers’ activities, the fort’s military band, movie screenings, and special visits to the fort’s USO Club, including Lena Horne, the Nicholas Brothers, and Langston Hughes. The Buffalo was even published in northern Italy when the 92nd was stationed there in 1945.

The Bullet (25th Infantry Regiment, 1928-1940s), the 93rd Blue Helmet (93rd Infantry Division, 1942-43), The Buffalo (92nd Infantry Division, 1943-45), The Apache Sentinel and it’s Postscripts (92nd Infantry Division, and the 32nd and 33rd companies of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps, 1943-45) – Each of these newspapers were published at Ft. Huachuca for segregated soldiers and members of the WAAC (later the Women’s Army Corps, or WAC) stationed there before and during World War II. Outside of talk about the war (when there was one), the papers talked about training, competitive sports (including info about the fort’s baseball team), soldiers’ activities, the fort’s military band, movie screenings, and special visits to the fort’s USO Club, including Lena Horne, the Nicholas Brothers, and Langston Hughes. The Buffalo was even published in northern Italy when the 92nd was stationed there in 1945.

You can find issues from most of these in-state papers online through the Arizona Memory Project digital newspaper database. Nationally, the Library of Congress Chronicling America digital archive has 238 African American newspapers (including some of the Arizona ones) available online. You can read every issue of Freedom’s Journal on the Wisconsin Historical Society website. Take an online tour of Phoenix’s African American Heritage, courtesy of the City of Phoenix Historic Preservation Office. Learn more about the Great Migration on our website, courtesy of Emancipation Arts, LLC.

Information for this article was found online at the above listed online newspaper databases; the Library of Congress Frederick Douglass Newspapers Collection, and Honoring African American Contributions: The Newspapers; PBS – Freedom’s Journal, The Black Press, the Afro-American Newspaper; the National Humanities Center – The Black Press; the Organization of American Historians – The Jim Crow-era Black Press; the Virginia Center for Digital History – History of African American Newspapers; ABC15 – Meet Ayra Hackett; the Equal Justice Initiative – Reconstruction in America; the Census – Arizona Population Demographics (1860-1990); the National Museum of African American History & Culture – The Chicago Defender; the National Women’s History Museum – Ida B. Wells; the National Park Service – Ida B. Wells.

Archive

-

2024

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-