Arizona at War – World War I

Posted July 1, 2023

Written by Heather Roberts, Research Historian

For a printable version of this article, please click here.

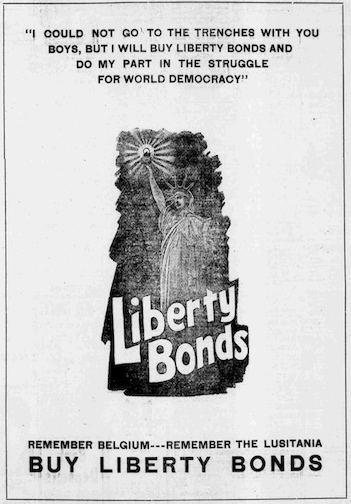

“The standard of respectability in America today is to own a home, own Liberty Bonds and have a war garden.” – Phoenix Tribune, August 24,1918

Did you know…

World War I may have started as a fight between neighboring nations Serbia and Austria-Hungary, but by its end over 30 countries across the globe were involved, along with tens of millions of soldiers. Though the fighting began in 1914, the United States stayed mostly neutral until early 1917, when a combination of an increase in German submarine attacks and the discovery of the Zimmerman Telegram – an encrypted message from Germany to Mexico, encouraging it to join the war on their side – made neutrality seem all but impossible.

America declared war in April 1917, and Congress quickly passed the Selective Service Act on May 18th, allowing the government to mobilize an army through conscription. On June 5th, all men between the ages of 21 and 31 were required to register for potential service (the draft age to would later be expanded to men between 18 and 45 years of age). The first draft numbers were randomly picked later that month, and the names of those chosen were published in local newspapers in July – among those listed in the July 17, 1917 Arizona Republican were Hazel (Goldberg) Melczer’s husband, Joseph, and Jesse Jean (Higley) Lane’s future husband, Eben. Both of Jesse Jean’s brothers were already in the military by that time – Thomas with the Marines, and James in officer training in Presidio, CA. Approximately 10,500 soldiers from Arizona would go on to serve during World War I. This included Native Americans as the first “code talkers”, though they weren’t yet recognized as American citizens; and African Americans, who were allowed in the draft over the protest of many southern politicians, and who served in segregated battalions doing jobs that were mostly menial and labor oriented (only the 92nd and 93rd Divisions saw combat in France). The October 18, 1917 Arizona Republican listed the 14 local African American men who had recently been drafted (the Phoenix Tribune, first Black owned and operated newspaper in Phoenix wasn’t established until the next year).

America declared war in April 1917, and Congress quickly passed the Selective Service Act on May 18th, allowing the government to mobilize an army through conscription. On June 5th, all men between the ages of 21 and 31 were required to register for potential service (the draft age to would later be expanded to men between 18 and 45 years of age). The first draft numbers were randomly picked later that month, and the names of those chosen were published in local newspapers in July – among those listed in the July 17, 1917 Arizona Republican were Hazel (Goldberg) Melczer’s husband, Joseph, and Jesse Jean (Higley) Lane’s future husband, Eben. Both of Jesse Jean’s brothers were already in the military by that time – Thomas with the Marines, and James in officer training in Presidio, CA. Approximately 10,500 soldiers from Arizona would go on to serve during World War I. This included Native Americans as the first “code talkers”, though they weren’t yet recognized as American citizens; and African Americans, who were allowed in the draft over the protest of many southern politicians, and who served in segregated battalions doing jobs that were mostly menial and labor oriented (only the 92nd and 93rd Divisions saw combat in France). The October 18, 1917 Arizona Republican listed the 14 local African American men who had recently been drafted (the Phoenix Tribune, first Black owned and operated newspaper in Phoenix wasn’t established until the next year).

With their sons and husbands leaving to fight, at home, America was preparing for war. Along with building an adequate fighting force, one of the top priorities the US government had was figuring out how to pay for the war. Taxes raised about a third of the money needed, but the majority of the war was financed with loans backed by government issued Liberty Bonds. An estimated 20 million Americans bought Liberty Bonds and, spending generally $50 to $100 per bond, raised over $17 billion for the war effort through four bond buying “campaigns”. (In case you’re wondering, $50 in 1917 is worth about $1100 today, and $17 billion in 1917 is worth over $400 billion today) Liberty Bond campaigns were promoted by everyone from local Girl and Boy Scout troops to famous celebrities like Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford. Names of people who bought bonds along with municipal bond totals were proudly touted in local newspapers. In Phoenix you’d find names on the list from Heritage Square families, including the Goldbergs, the Silvas, the Gammels, and the Haustgens. Ed Haustgen – brother to Anna and Marguerite Haustgen of Heritage Square – also sold a Heifer calf at auction to support the Red Cross in 1918, raising $85 ($2019 today).

-

Women and the National Service School

In 1916, the National Service School was created to train women to serve their country if the US became involved in World War I. From the National Archives, here’s a video they found of some of that training:

The American Red Cross were involved in the war from the start when they launched their “Mercy Ship” to help war wounded soon after hostilities began. They also staffed, stocked, and supported hospitals along the front lines, caring for all casualties. But when the US joined the war, their efforts focused primarily on care for American and Allied troops. Back home, the Red Cross accepted donations of money and materials to support their efforts, and built a corps of 8 million volunteers and 31 million member donors by the end of the war. The volunteers included 12,000 women who joined the Red Cross Women’s Motor Corps, driving ambulances at home (though 300 would do so abroad), and over 22,000 women who were recruited and professionally trained as nurses. The nurses would go on to work for the US Army and Navy, for British and French units, and for the Red Cross itself (though African American nurses were not allowed to serve overseas). Almost half would work at or near the front lines, with 330 casualties.  Most Red Cross volunteers, however, worked from the safety of their homes and communities, knitting socks and sweaters, rolling bandages, making surgical dressings, and putting together care packages for the troops. Many national and local women’s groups would meet specifically to do volunteer work for the Red Cross, including the Phoenix Coterie Club, the Colored Chapter of the Red Cross (Somerton, AZ), the Young Women’s Christian Association, and the Arizona Federation of Colored Women. Carrie Goldberg was mentioned at the end of the war in a list of Red Cross volunteers. The YMCA and Salvation Army were similarly involved, mobilizing community support for the war effort.

Most Red Cross volunteers, however, worked from the safety of their homes and communities, knitting socks and sweaters, rolling bandages, making surgical dressings, and putting together care packages for the troops. Many national and local women’s groups would meet specifically to do volunteer work for the Red Cross, including the Phoenix Coterie Club, the Colored Chapter of the Red Cross (Somerton, AZ), the Young Women’s Christian Association, and the Arizona Federation of Colored Women. Carrie Goldberg was mentioned at the end of the war in a list of Red Cross volunteers. The YMCA and Salvation Army were similarly involved, mobilizing community support for the war effort.

If sewing and nursing weren’t someone’s strong points, there was always other war work available. Labor shortages meant that women and people of color were hired for jobs that had previously been held by white men. Across the nation, women worked as ticket takers, railroad conductors and laborers, bank clerks, elevator operators, and “farmerettes” (women who worked in the Women’s Land Army and other organizations to help with the agricultural labor shortage). They also worked in factories, machine shops, steel mills, and munitions plants, making pieces that were critical to the war effort. White women were hired by the Navy to work in the US as clerks and secretaries, and 233 “Hello Girls” (white, bilingual telephone operators) were recruited to join the Signal Corps in France. They did amazing communications work, sometimes in combat areas, and didn’t receive official government recognition of their service, including military benefits, until 1977.

-

No Wife Left Behind

Hazel Carter, c1917, US National Archives

Not all women were satisfied with letting their sons or husbands leave to train for or fight in the war without them. Most would follow their loved ones to the places they were stationed before being sent overseas. When James Higley was stationed at Camp Lewis in Washington state, his mother and sister spent time there as well. And when Hazel (Goldberg) Melczer’s husband, Joseph, was stationed at Fort Riley, Kansas, she took their children and followed him there. But one Arizona woman went a step further. Hazel Carter of Douglas, AZ, decided to follow her husband, John, overseas. She cropped her hair, stole a military uniform, and was able to sneak aboard both the troop train and the transport ship her husband was on before being discovered. When news spread of her attempt, her grandfather, a Civil War veteran, was quoted as saying, “I knew she would do it…That girl sure has grit. I wish she could stay and fight the Germans. You ought to have seen her in uniform. She made a better looking soldier than John, I do believe. She can handle a rifle better than most men. They sure should have let her stay.” Upon her return, her story about her adventure was picked up by newspapers across the nation. Read about it in her own words – The Girl Who Was a Soldier Boy by Hazel Carter from the Moscow, Idaho Daily Star-Mirror.

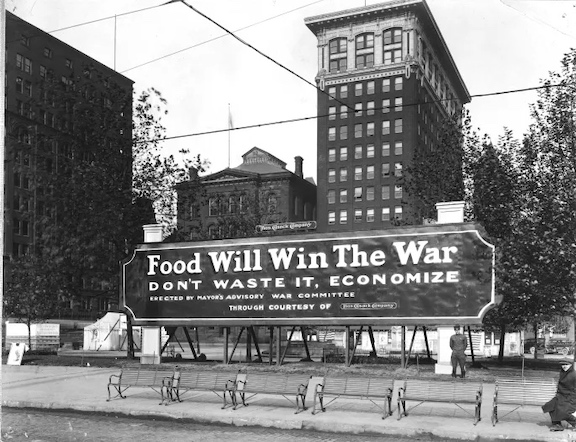

On top of war work, the war affected everyday civilian life, too. Food shortages were prevalent as America attempted to feed its own people at home and abroad, and the armies and citizens of its allies as well. The US government instituted voluntary rationing of food, relying on people to self-sacrifice for the good of the country. They called for “Meatless Mondays”, “Wheatless Wednesdays”, and “Porkless Thursdays and Saturdays”, and asked people to find substitutes for high demand foods, promoting use of non-wheat flours, potatoes, and sweeteners like corn syrup instead of sugar. They also asked people to eat locally sourced food and to start their own War Gardens to conserve resources. The US Fuel Administration implemented mandatory war rationing, with “Lightless Nights” on Thursdays and Sundays in 1917, and in 1918 introduced “Heatless and Workless Mondays”, “Gasless Sundays”, and even something new called Daylight Saving Time. “Lightless Nights” required all electrical signs to be turned off on those days and most other electrical lighting to be reduced or turned off as well. The first “Heatless and Workless” day on January 21, 1918 was reported as “wonderful” by fuel administrators. However, the report didn’t include how the public felt being “heatless” in January, though Arizona may have been able to manage it better than the rest of the country! “Gasless Sundays”, established later that year, required all car dealers, auto shops, and tire shops to be closed Sundays each week, along with all but one gas pump and mechanic’s garage (to be left open for emergencies). The August 4, 1918 edition of the Arizona Republican listed the Washington Street Garage at 806 W. Washington (about a mile west of Rosson House) as the emergency station for that day. The government also put price controls on food and fuel, so that high demand didn’t cause prices to skyrocket.

On top of war work, the war affected everyday civilian life, too. Food shortages were prevalent as America attempted to feed its own people at home and abroad, and the armies and citizens of its allies as well. The US government instituted voluntary rationing of food, relying on people to self-sacrifice for the good of the country. They called for “Meatless Mondays”, “Wheatless Wednesdays”, and “Porkless Thursdays and Saturdays”, and asked people to find substitutes for high demand foods, promoting use of non-wheat flours, potatoes, and sweeteners like corn syrup instead of sugar. They also asked people to eat locally sourced food and to start their own War Gardens to conserve resources. The US Fuel Administration implemented mandatory war rationing, with “Lightless Nights” on Thursdays and Sundays in 1917, and in 1918 introduced “Heatless and Workless Mondays”, “Gasless Sundays”, and even something new called Daylight Saving Time. “Lightless Nights” required all electrical signs to be turned off on those days and most other electrical lighting to be reduced or turned off as well. The first “Heatless and Workless” day on January 21, 1918 was reported as “wonderful” by fuel administrators. However, the report didn’t include how the public felt being “heatless” in January, though Arizona may have been able to manage it better than the rest of the country! “Gasless Sundays”, established later that year, required all car dealers, auto shops, and tire shops to be closed Sundays each week, along with all but one gas pump and mechanic’s garage (to be left open for emergencies). The August 4, 1918 edition of the Arizona Republican listed the Washington Street Garage at 806 W. Washington (about a mile west of Rosson House) as the emergency station for that day. The government also put price controls on food and fuel, so that high demand didn’t cause prices to skyrocket.

Almost a year into the war, the news from the front seemed as usual as the armies tried to fight through the stalemate of horrific trench warfare. But in Kansas, an outbreak of influenza among soldiers stationed at Fort Riley changed everything. It hospitalized 500 soldiers within one week in March 1918, and by fall the virus had spread around the world by soldiers’ widespread travel and close living quarters. As we’re far more familiar with than we’d like to be, in the fall of 1918, everyday life on the homefront was characterized by people getting sick, being quarantined, and sometimes dying within days; and businesses, schools, and churches closing for the safety of the community. On both sides of the conflict, influenza not only affected civilians’ ability to support the war, but the soldiers’ ability to fight it as well. It may have influenced the decision of Austria-Hungary and her allies to seek the armistice that ended the conflict. On November 11, 1918 at 11am, the shooting stopped and the war ended.

Almost a year into the war, the news from the front seemed as usual as the armies tried to fight through the stalemate of horrific trench warfare. But in Kansas, an outbreak of influenza among soldiers stationed at Fort Riley changed everything. It hospitalized 500 soldiers within one week in March 1918, and by fall the virus had spread around the world by soldiers’ widespread travel and close living quarters. As we’re far more familiar with than we’d like to be, in the fall of 1918, everyday life on the homefront was characterized by people getting sick, being quarantined, and sometimes dying within days; and businesses, schools, and churches closing for the safety of the community. On both sides of the conflict, influenza not only affected civilians’ ability to support the war, but the soldiers’ ability to fight it as well. It may have influenced the decision of Austria-Hungary and her allies to seek the armistice that ended the conflict. On November 11, 1918 at 11am, the shooting stopped and the war ended.

Though the “War to End All Wars” was over, the changes it created were long lasting. Waves of influenza were still affecting people through 1920, killing an estimated 50 million people worldwide (compared to the 16 million soldiers and civilians killed in the war). War recovery and reparations burdened many countries for decades economically. In America, women who had tasted freedom with war work redoubled their efforts for national suffrage, and were successful in August 1920. African American soldiers who had discovered in Europe a new world outside of American racism and segregation worked with the NAACP (est. 1908) and other organizations to protest racial inequities and Jim Crow laws. They and their families would continue a mass exodus out of the American south to other parts of the country, looking for jobs, opportunities, and safer communities in what is now known as the Great Migration. Native American soldiers who served in the military during World War I were granted citizenship in 1919, and as a whole American indigenous peoples were finally recognized as American citizens in 1924. In Arizona, the war had boosted our economy, with cotton, copper, and cattle (beef) in high demand. But after the war, prices for those commodities plummeted, suffered further during the Great Depression, and didn’t fully recover until the next world war.

Unfortunately, the end of the Great War came a month and a half too late for the Higley family, who lost their son and brother, James, on September 28, 1918. You can learn more about him in our prior blog article, Remembrance.

Explore gardening during World War I and other key times in American history from our Victory Gardens blog article. Learn more about how the 1918 influenza epidemic affected schools and businesses in Arizona and the US from our School’s Out blog article.

Learn about the Red Summer – racial violence that followed the end of the war, primarily targeted against Black World War I veterans, from the National Archives records. Not everything in Arizona was smooth sailing during the war, either – learn about the 1917 Bisbee Deportation, courtesy of the University of Arizona libraries special collections. From the centennial of the World War I armistice, read Family stories of loved ones’ WWI service shared by Arizona Daily Star readers. Learn about Arizona’s car from the Merci Train, an expression of gratitude from France to the American people after World War I, from the Arizona Capitol Museum online exhibit.

Information for this article was found online at the Library of Congress Chronicling America digital newspaper archive (Arizona Republican and Phoenix Tribune newspapers, April 1917 through December 1918); the Library of Congress digital collections – The American Expeditionary Forces; the Library of Congress exhibitions – World War I and Postwar Society; the Library of Congress blog – World War I: The Women’s Land Army; The United States World War I Centennial Commission – The Homefront; the American Battle Monuments Commission – Hometown Boys from Arizona: Information and Statistics about WWI Service Members; the National WWI Museum and Memorial – How World War I Changed America, and their WWI A-Z exhibit online; the National Park Service – Women in World War I; PBS – American Nurses in World War I; The National Archives Museum – Honoring Native American Soldiers World War I Service; the National Archives – World War I Draft Registration Cards, The Women of World War I in Photographs, and The Zimmerman Telegram; National Women’s History Museum – Women of the Red Cross Motor Corps in WWI; and Women’s Land Army of World War I; the US Army – Hello Girls of World War I; the Imperial War Museums – 5 Things You Need To Know About The First World War; the Federal Reserve History – Liberty Bonds; the American Social History Project – Black Workers During World War I; the University of Washington – Where Women Worked during World War I; Atlas Obscura – The Meatless, Wheatless Meals of World War I America; Smithsonian Magazine – Women On the Frontlines of WWI Came to Operate Telephones; Central Connecticut State University library – Women in the Factories; National Museum of the American Indian – Why We Serve; Kansas Historical Society – Flu Pandemic of 1918; the Red Cross – World War I and the American Red Cross (PDF); Genealogy Bank: The WWI Soldier Girl: Hazel Blauser Carter.

Archive

-

2024

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-