“And the best of all ways

To lengthen our days

Is to steal a few hours from the night…”

– Thomas Moore, “The Young May Moon”

It’s About Time

For a printable version of this article, please click here.

Did you know…

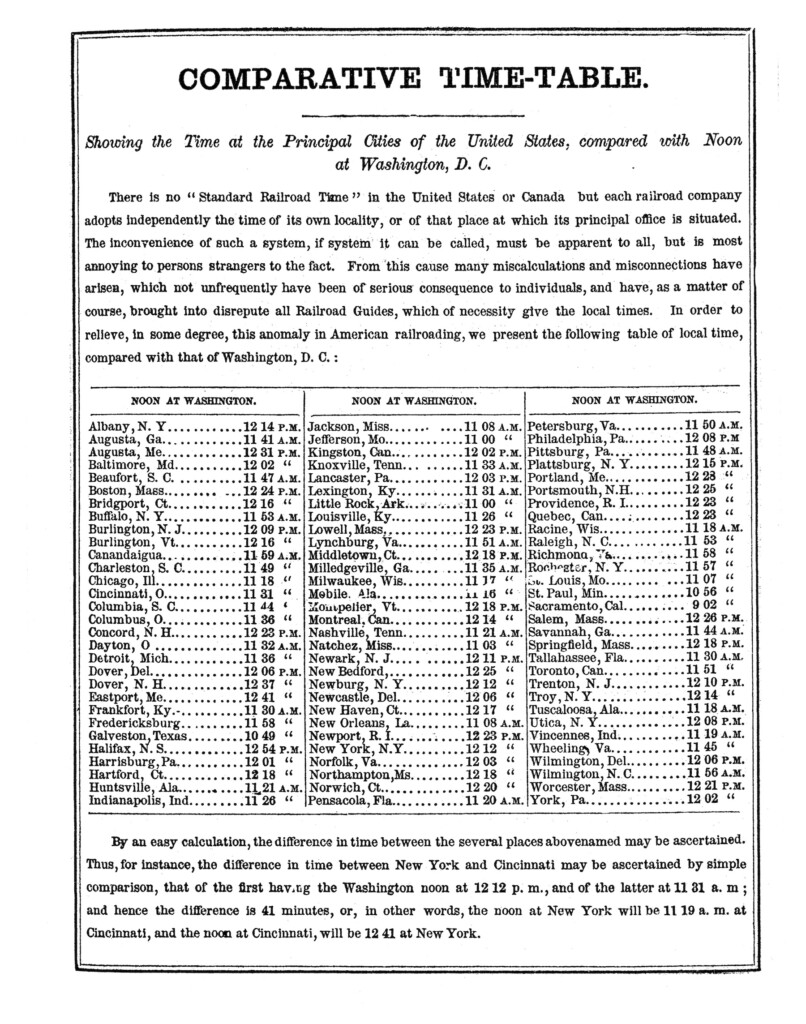

Table from the 1868 Travelers’ Official Railroad Guide of the US and Canada, showing the difference in recorded times for each locale.

It’s the beginning of November, which means that while most of the country will be “falling back” with their clocks this upcoming Sunday, we in Arizona can continue ignoring Daylight Saving Time as usual, our sleep schedule safely undisturbed. But why doesn’t Arizona observe the bi-annual changing of the clocks that is Daylight Saving Time – going forward one hour in the spring and falling back one hour in the autumn – and why do we even have the time change anyway? Well, like a lot of things we talk about here, it all starts with the railroad.

Railroad Time

Daylight Saving Time wouldn’t exist without standardized time zones, which wouldn’t exist without the railroad. Locally, time had long been kept according to the position of the sun at midday, and shared by clocks in town squares and/or bells from church steeples. This meant that time could be customized to specific locales, but also meant that timekeeping could vary from one town to the next, or even one part of town to the next. When trains came on the scene, that meant their schedules were all over the clock, literally, with potentially hundreds of individual local times across the US

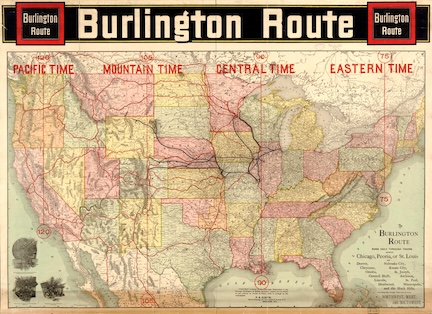

1892 map with the railroad time zones marked, via the Library of Congress.

Beyond a passenger missing their train because their pocket watch was off from the station time, trains being on different times from each other could have deadly consequences. Railroad companies shared tens of thousands of miles of track – much of it single lines for both inbound and outbound train traffic. That led to terrible accidents like the Great Train Wreck of 1856 (Philadelphia, PA) and the Great Revere Train Wreck of 1871 (Revere, MA), where trains collided because of unexpected traffic, causing multiple fatalities. To combat this problem, lights and signals were added to trains, but didn’t always work. In 1870, a Connecticut school teacher named Charles Dowd met with railroad companies to suggest a move toward four main time zones for the United States, with the boundaries defined at the 75th, 90th, 105th, and 120th meridians. Unfortunately, the almost 500 (!!) railroad companies declined to work with each other to solve the problem at that time. It wasn’t until 1883 that they were persuaded to try using time zones to make their trains safer and more reliable, ushering in what was called “Railroad Time” on November 18, 1883. Though many people adopted the new time because it was more convenient than keeping track of local and railroad times, the US government wouldn’t establish time zones by law for another 35 years.

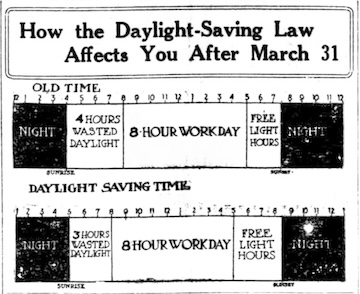

Clip from The Washington Herald newspaper, March 16, 1918.

Daylight Saving Time – a seasonal time change that doesn’t save daylight as much as it allows for better use of daylight – wasn’t adopted until the early 20th century. However, it had been discussed as early as 1784 by Benjamin Franklin in a tongue-in-cheek essay published in the Journal de Paris, where he suggested that getting up at daybreak and going to bed earlier would save Parisians from having to buy so many candles. The broader concept of a seasonal time adjustment was first officially proposed in New Zealand by entomologist George Hudson the year Rosson House was built (1895), and English builder and Member of Parliament, William Willet, proposed a similar change in his 1907 pamphlet, The Waste of Daylight. But it wasn’t until times of war and emergency that anyone decided it was necessary, beginning with World War I.

War Time

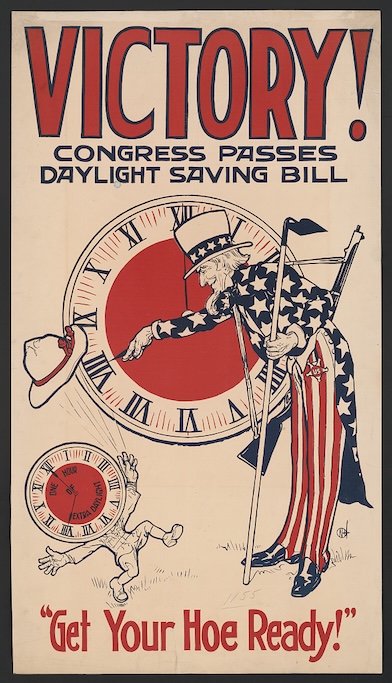

In an effort to save coal by reducing use of artificial lights, Germany became the first country to officially adopt a seasonal time change on May 1, 1916, shortly followed by Austria-Hungary, England, and several other European countries. The United States was finally successful in passing their Daylight Saving legislation on March 19, 1918, with the time change going into effect on April 1st (no joke!). The law – the Standard Time or Calder Act – also formalized the US time zones. The Chamber of Commerce and sports and recreation industries were instrumental in getting the law passed, seeing it as a way not only to save energy but also a way to boost the economy, but the movie and agricultural industries were opposed to the change. After the war ended, a law was passed to repeal Daylight Saving Time, which Congress voted for over President Wilson’s veto – twice. But when the US entered the second world war, it didn’t take long for Congress to reestablish a national, year-round Daylight Saving Time, again arguing that it would save precious energy resources. They authorized the War Time Act in January 1942, again over protest from the agricultural community, and the law was repealed in September 1945, shortly after the end of the war.

-

What time is it?!

Daylight Saving Time in the US during World War II was pretty straightforward, bumping the time one hour ahead for each time zone. But in war torn Europe, things were not that simple. England – who has just one time zone – had already followed what’s called British Summer Time at the outbreak of World War II, and decided not to “fall back” in the autumn of 1940 as they usually would, staying with the seasonal time change through the following year. But instead of turning their clocks back at that time, they put them forward again, making their time two hours ahead of their standard, creating Double Summer Time. This not only saved energy, but gave people extra time at the end of their work day to make it home before blackout restrictions began. The countries who were occupied by the Nazis during the war were forced to be on the same time as Germany, who observed a double time change as well, and would change back when they were liberated by the Allies. In 1945, Soviet-occupied Berlin was required to be on the same time zone as Moscow, a two-hour difference, as were other Soviet-occupied areas of Europe. So, for Europe, the time really depended on who was in charge more than where your location was during the war.

Daylight Saving Time in the US during World War II was pretty straightforward, bumping the time one hour ahead for each time zone. But in war torn Europe, things were not that simple. England – who has just one time zone – had already followed what’s called British Summer Time at the outbreak of World War II, and decided not to “fall back” in the autumn of 1940 as they usually would, staying with the seasonal time change through the following year. But instead of turning their clocks back at that time, they put them forward again, making their time two hours ahead of their standard, creating Double Summer Time. This not only saved energy, but gave people extra time at the end of their work day to make it home before blackout restrictions began. The countries who were occupied by the Nazis during the war were forced to be on the same time as Germany, who observed a double time change as well, and would change back when they were liberated by the Allies. In 1945, Soviet-occupied Berlin was required to be on the same time zone as Moscow, a two-hour difference, as were other Soviet-occupied areas of Europe. So, for Europe, the time really depended on who was in charge more than where your location was during the war.

After World War II, there was no federal law mandating or regulating Daylight Saving Time, and so everyone winged it. Generally, urban areas preferred the change while rural areas did not – for example, Denver, CO adopted DST while the rest of the state kept to standard time. Sometimes this didn’t lead to just one time change, though, but many. A reported trip from Steubenville, OH, to Moundsville, WV, passed through seven different time changes within 35 miles. Iowa communities in 1964 had twenty-three separate set of dates when the seasonal time change stopped and started. The 1966 Congressional Quarterly Almanac reported:

After World War II, there was no federal law mandating or regulating Daylight Saving Time, and so everyone winged it. Generally, urban areas preferred the change while rural areas did not – for example, Denver, CO adopted DST while the rest of the state kept to standard time. Sometimes this didn’t lead to just one time change, though, but many. A reported trip from Steubenville, OH, to Moundsville, WV, passed through seven different time changes within 35 miles. Iowa communities in 1964 had twenty-three separate set of dates when the seasonal time change stopped and started. The 1966 Congressional Quarterly Almanac reported:

The Committee for Time Uniformity reported in 1965 that only 12 states, most of them in the South, remained entirely on standard time; 18 states observed statewide DST, 15 of these from the end of April to the end of October; 18 others adopted some form of DST “by local option for periods varying from three to six months”; and portions of two states, North Dakota and Texas, observed “daylight in reverse”–an hour behind standard time.

To avoid this incredibly confusing, patchwork quilt of different times all over the country, Congress passed the Uniform Time Act, requiring that states either opt in or out of Daylight Saving Time entirely, though not allowing them to take up DST year-round. Two states decided to adopt standard time permanently – Hawaii in 1967, and Arizona the following year (except for the Navajo Nation, which continues to observe DST). The 1970s Oil Crisis led to Congress passing the Emergency Daylight Saving Energy Conservation Act of 1973, and the entire nation once again observed Daylight Saving Time for most of 1974 before backlash caused the law to be repealed. Arizona received an exemption from that emergency time change, arguing, as it had in 1968, that the amount of sun we get in Arizona during the summer is plenty! Daylight Saving Time has been altered twice since then, in 1986 and 2005, officially changing the dates the time change starts and stops. Currently, Daylight Saving Time starts the second Sunday in March and ends on the first Sunday in November.

The fight over whether to have Daylight Saving Time or not continues. In 2008, the Department of Energy reported energy consumption decreased during DST by 0.02%, but reported that DST energy consumption also seems to vary widely depending on where people live. Health issues are also at the core of the Daylight Saving Time question, as risks of heart attacks and car accidents are increased after seasonal time changes. Many states have at least looked into the possibility of either ending the time change permanently (like Hawaii and Arizona did), or of observing DST permanently (which is currently not allowed under the Uniform Time Act). Nineteen states have passed legislation to adopt a permanent Daylight Saving Time once federal law allows them to do so, including Alabama, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Minnesota, Mississippi, Montana, Ohio, Oregon, South Carolina, Tennessee, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. In 2022, the US Senate passed the Sunshine Protection Act – a bill to make Daylight Saving Time permanent for most US states and territories. It was introduced in the House in early 2023, but nothing has progressed so far.

Information for this article was found online from Library of Congress – The Day of Two Noons and In Custodia Legis: Spring Forward, Fall Back…; JSTOR Daily – How America Got its Time Zones; Union Pacific – Surprising Railroad Inventions: US Time Zones; Bureau of Transportation Statistics – History of Time Zones and Daylight Savings Time; The History Teacher (JSTOR) – The Times They Are A-Changing: The Influence of Railroad Technology on the Adoption of Standard Time Zones in 1883; ThoughtCo – The History and Use of Time Zones; The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia – Train Derailments and Collisions; NPR – A Time-Change Timeline; Seize the Daylight: A History of Clock Chaos; Madison Historical Society – Charles Ferdinand Dowd (1825-1904); The Franklin Institute – Did Ben Franklin Invent Daylight Saving Time? ; TEARA (The Encyclopedia of New Zealand) – George Vernon Hudson; Royal Museums Greenwich – Why do the Clocks Change?; National Museums Scotland – The Waste of Daylight; US National Archives: The Text Message – Daylight Saving Time Begins, 1916; Time Magazine – The Real Reason Why Daylight Savings Time is a Thing and When Daylight Saving Time was Year-Round; Atlas Obscura – The Extreme Daylight Savings Time of World War II; The Conversation – 100 Years Later, the Madness of Daylight Saving Time Endures; Smithsonian Magazine – What Happened the Last Time the U.S. Tried to Make Daylight Saving Time Permanent?; Pima County Public Library – Daylight Saving Time: Tucson & Arizona; Congressional Research Service – Daylight Saving Time (DST) Report (PDF); Congressional Quarterly Almanac (1966) – Uniform Observance of Daylight Saving Time; Sleep Foundation – Latest updates: Daylight saving time in 2023; Johns Hopkins (Bloomberg School of Public Health) – 7 Things to Know About Daylight Saving Time.

Archive

-

2024

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-