Victorian Laundry

For a printable version of this article, please click here.

Did you know…

Without your fancy, front loading, high-efficiency, smart washer and dryer, specialized detergents and other laundry supplies, and wrinkle-free fabrics, just how long would it take for you to do laundry in the late 19th century?

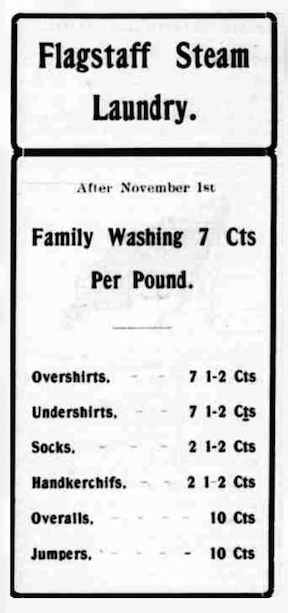

Well, if you were lucky enough to afford hiring someone else do your laundry for you, either by sending it out or by having someone in your home dedicated to doing household laundry, then you wouldn’t have to worry about how long it took to do laundry at all. We don’t know who amongst the families who lived at Heritage Square sent out their laundry or what it cost, but we do know that there were eight laundry businesses mentioned in the 1895 Phoenix City Directory, and eighteen in 1898. (Side note: Five of the laundries in 1895 were operated by Chinese men, and six of the laundries in 1898. Learn more about how racism and laws like the Chinese Exclusion Act affected Chinese immigrants and pushed them towards working in “undesirable” jobs like running laundries by reading this article.)

Well, if you were lucky enough to afford hiring someone else do your laundry for you, either by sending it out or by having someone in your home dedicated to doing household laundry, then you wouldn’t have to worry about how long it took to do laundry at all. We don’t know who amongst the families who lived at Heritage Square sent out their laundry or what it cost, but we do know that there were eight laundry businesses mentioned in the 1895 Phoenix City Directory, and eighteen in 1898. (Side note: Five of the laundries in 1895 were operated by Chinese men, and six of the laundries in 1898. Learn more about how racism and laws like the Chinese Exclusion Act affected Chinese immigrants and pushed them towards working in “undesirable” jobs like running laundries by reading this article.)

If you had to do it yourself, doing laundry in the late 19th century was a complicated, hot, sweaty, backbreakingly heavy, week-long (every week with no holidays) processes that included boiling clothing and linens over a hot stove/fire and pressing them with an iron that could only be heated on a hot stove – sure sounds like fun on a Phoenix summer day! According to The American Pure Food Cook Book and Household Economist (c1899), they suggest starting laundry on Monday (or Tuesday, if you have other chores to be done first), having a plan to:

1) Prep the clothing/linens, including assembling, sorting, mending, and treating stains.

2) Soap and soak clothing/linens (for a couple hours or overnight), making sure to soak whites in warm water.

3) Rinse out dyed clothes, silk underwear, and flannels, and wash in cold water (never use soak water for washing). Wash handkerchiefs by themselves, particularly if they’ve been used by someone with a cold (yuck!). Scrub stained clothing/linens with a tub and washboard, taking care not to damage the cloth, and not to strain your back by stooping too much. Wring out clothes/linen before boiling.

4) All white clothes/linen should be boiled for 15-20 minutes in soft water with enough soap to create a slight lather, keeping them submerged with a clean paddle or stick. Sick room linens should be boiled for a half an hour.

5) Rinse everything in clean tub half-filled with warm water. If needed, a second rinse in cold water is permissible.

5) Rinse everything in clean tub half-filled with warm water. If needed, a second rinse in cold water is permissible.

6) Put bluing agent in clean tub with hot water and work around until the water is a sky-blue color. Immerse white clothing/linens individually, removing and wringing each time, and stirring the tub well so that the bluing doesn’t settle to the bottom. If a garment isn’t blue enough, immerse again. If it’s too blue, rinse in clean water. Hang all clothing/linen on a line to dry, unless it needs to be lightly (thin) starched first.

7) Make thin starch by combining starch (powder), lard, and cold water, and adding it to boiling water, adding enough bluing to counter the natural yellowing of the starch. Allow to cool. Make thick starch by combining starch (powder), cold water, and paraffin wax shavings, and adding it to boiling water, adding enough bluing to counter the natural yellowing of the starch. Allow to cool. Some clothing/linens should be completely immersed in the starch, and with others it should be carefully applied to the part of the garment that needs stiffened. Starched clothing/linens should be hand wrung and not run through the wringer.

8) Dry clothing as often as possible on a line outside, as sunshine freshens and purifies them, using a clean clothesline and clothespins.

9) On a clean table with clean, tepid water, lay out each article of clothing or linen, and uniformly sprinkle with water using your fingers or a clean whisk broom. After dampening all over, roll firmly and pack in a basket for a few hours or overnight. In hot weather (attention Phoenix!), if all the clothes cannot be ironed the next day, shake them out and dry them, “for the damp clothes may mildew and the starched clothes sour.”

Rosson House pleating or crimping iron, used to press ruffles or pleats in clothing.

10) To iron you’ll need an ironing board or table tightly covered with a clean blanket, a clean ironing sheet, beeswax, an iron stand, clean irons, a bowl of clear water, a clean, soft cloth, brown paper, an old piece of cloth, and a large piece of paper or cloth to protect clothes/linens that may touch the floor. Keep irons clean and moisture-free or they will rust. Test the heat of an iron by bringing it within three or four inches of your cheek (!!) – if it is too hot to stay there for a few seconds, it’s too hot for your clothing/linens. Shake or stretch the cloth into shape and iron until the cloth is dry. Sprinkle or dampen articles like sheets, handkerchiefs, table clothes, towels, napkins, corset covers, cuffs, collars, shirts, skirts, night shirts/dresses, and drawers with starch before ironing or using a pleating iron when creating ruffles. Fold depending on the shape of the article.

11) Always air out your garments/linens after they’re ironed by hanging them on clothes-bars before they’re put away, to avoid having a musty odor.

12) Back to square one with mending anything that wasn’t fixed before washing, including darning socks, repairing rips, mending sagging hems, replacing lost beads and buttons, etc!

Washing laundry usually relied heavily on soap made of lye – also called caustic soda or potassium hydroxide – or even just lye itself. Lye is an alkaline solution made through a process of filtering water through hardwood ashes, and is helpful with removing grease and loosening dirt from linens. **Warning – Lye is a harsh chemical that can burn skin, eyes, and other tissues, so you do not want to play around with it without proper protection!**) But not all clothing was washed. Finer clothes, particularly those with bright dyes and with heavy embroidery and beading were only cleaned if they were stained, and even then most of the time the stain was treated instead of the entire garment itself. Undergarments like chemises, undershirts, and underwear/drawers were made to absorb sweat and dirt, protecting outer clothing from becoming soiled through wear while those articles could be boiled and scrubbed like other linens.

Laundry day, c1900, Forks Timber Museum, Washington

Women who could afford to do so would have a washer woman to help with the laundry, but would more likely have had a daughter or two who pitched in with laundry and other chores. If she was lucky, she had a box or cold press mangle to iron linens and some clothing, cutting ironing time dramatically. Mechanical clothes washers like our Happy Home Steam Washer helped agitate laundry to get it clean, but it still had to be placed on a hot stove and the handle cranked. Though the Happy Home was made around 1915, as early 15 years earlier separate electric motors could be added to hand, crank, or treadle operated mechanical washers – like our 1900 Washer Company washer (with its Coffield Washer Co. motor), on the Rosson House back porch. The first electric washer was invented in 1908 by Alva Fischer, and the first fully automatic Bendix washing machine in 1937. African American inventor George T. Sampson invented a process to dry clothes using rods suspended over a specially designed stove in 1892, and the first electric, tumble-dry clothes dryer was invented in 1937 by J. Ross Moore. These labor-saving devices allowed women to have more free time and move towards participating in the workforce. How much time was saved? In 1900, a woman could spend an average of 58 hours a week on housework, including cooking, doing laundry, and cleaning. By 1975, this number dropped to 18 hours. In 1940, over 40% of American households had a clothes washer; by 2016, over 85% did. Clothes dryers were a little slower to be adopted – in 1955 only 10% of US households had one, and by 2009 almost 80% had a clothes dryer.

Information for this article was found in the Heritage Square archives; The American Pure Food Cook Book and Household Economist by David Chidlow (c1899); Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management (c1869); the 1895 and 1898 Phoenix City Directories; Library of Congress Chronicling America digital archive; the Homestead National Historical Park website (their info about the cold press mangle is really good); the Living History Museum; the Museum of History & Industry digital collection; Atlas Obscura; ThoughtCo; Penn Today; Bloomberg; Evolution of Home Appliances; and Statista.

Archive

-

2024

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-