Tricks Before Treats: How Victorian Mayhem Gave Us Our Modern Halloween

Posted October 1, 2023

Written by Merry Gordon, Heritage Square Volunteer

For a printable version of this article, please click here.

Did you know…

When you ring your neighbor’s doorbell on October 31st, don’t forget to tip your hat to your forebears: it turns out we owe a debt of gratitude to those early tricksters for our Halloween treats! On All Hallows’ Eve – later Halloween – the veil between the living and the dead was supposed to be especially thin and celebrants disguised themselves as the same ghosts and goblins they feared. The pagan celebration may have borrowed from the Christmas tradition of belsnickeling, in which participants performed small tricks in exchange for refreshments, but by the Victorian era, Halloween took on a life of its own.[1]

Halloween tricks and treats was a part of Phoenix from its early years. The burgeoning metropolis boasted its fair share of Halloween parties among the well-heeled. Early town luminaries enjoyed the “trick” of dressing up as historical figures at costume parties – the Marquis de Lafayette and the Queen of Sheba, to name a few.[2] A lavish 1898 soirée hosted by Mrs. J.M. Swetnam beckoned guests with lines from Macbeth and boasted an indoor tent with skull and illuminated pumpkin, “the effect being very weird.” The terrifying treat of a ghost story contest ensued, for which a paper doll representing a devil was awarded as first prize. Fortunes were read by a mysterious figure in a fancy red robe called a “domino” – later revealed to be Mrs. Nora Kibbey, the wife of Associate Justice J.H. Kibbey of the Arizona Territorial Supreme Court.[3]

But aside from a smattering of social events, Halloween in early Phoenix was far more trick than treat, with children running amok in an orgy of mayhem and property destruction. In 1895, a band of youngsters was spotted overturning the bridges over the irrigation ditches with a rope and a hay hook. They were halfway through upending another when the cry “Cheese it! Here come the cops!” sent the boys scrambling. That same night, another group rigged a wire in front of a door and threw stones at the house until a hapless man charged out, effectively clotheslining himself to the hoots and hollers of the boys. The evening patrollers hauled in a handful of the boys and spooked them by clapping them in jail before releasing them with a stern reprimand.[4]

Not to be outdone, the young ladies of Phoenix went on the rampage that year too. A group of girls – who may or may not have been clad in bloomers – took over buggy wheels, removed front gates, and strung wires across nails at Sam Sneed’s doorstep to trip him.[5]

By 1898, the property destruction had grown worse. The town looked “as if it had been buffeted by a Kansas cyclone,” with signs and gates misplaced, crosswalks cut down and drains and gutters torn out. On 5th Avenue, a horse had been stolen.

Halloween chaos reached a fever pitch in the early 20th century. Childish hoodlums all across the nation pushed social limits as their pranks became more anarchical than adorable. This pandemonium ended in fatality at least twice in our young state, with one teenage prankster gunned down by a Douglas couple in 1913 and a young Tombstone hooligan shot to death in the act of stealing a wagon a year later.[6],[7]

Something had to be done. Children were already demanding money and candy as they tore their way through American towns. A rebranding effort all across the nation, beginning in the mid-1900s and assisted by clever food marketers, resulted in the more civilized door-to-door candy drive Halloween is better known for today. The fancy costume parties of old were brought outdoors and ritualized: “Since there were children already out demanding sweets or money, why not turn it into a constructive tradition?” asks Smithsonian Magazine writer Lesley Bannatyne. “Teach them how to politely ask for sweets from neighbors, and urge adults to have treats at the ready.”[8] Civility – and commercialization – won out.

Something had to be done. Children were already demanding money and candy as they tore their way through American towns. A rebranding effort all across the nation, beginning in the mid-1900s and assisted by clever food marketers, resulted in the more civilized door-to-door candy drive Halloween is better known for today. The fancy costume parties of old were brought outdoors and ritualized: “Since there were children already out demanding sweets or money, why not turn it into a constructive tradition?” asks Smithsonian Magazine writer Lesley Bannatyne. “Teach them how to politely ask for sweets from neighbors, and urge adults to have treats at the ready.”[8] Civility – and commercialization – won out.

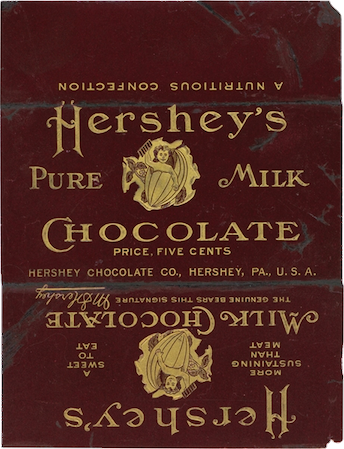

Some of the candies in our modern Halloween buckets go back to these early days of trickery. Such commercially available sweet treats would have gladdened the heart of any early Phoenix mischief-maker. Jujubes were around by the mid-1870s.[9] The pill-shaped licorice delights known as Good & Plenty go back as early as 1893, produced by Philadelphia’s Quaker City Chocolate & Confectionery Company.[10] Tootsie Rolls, named for the manufacturer’s daughter and offered for a mere penny, were first manufactured in 1896.[11] Finally, the iconic Hershey’s Milk Chocolate Bar was first sold in 1900.[12]

Phoenix did have a handful of confectioners by the 1890s, but candy was usually more associated with Christmas. Besides, wary Victorians were loathe to overdo it on the sweets – one Arizona newspaper warned about the terrors of “candy heart,” a tragic condition that tended to strike young women with a predilection for the candy shop: “First, she becomes listless and languid; her complexion becomes sallow; her eyes lose their luster; she years for the unattainable; her days are passed in a strange atmosphere of deep-blue haziness. In time, the tissues of her heart change to the fiber of jujube paste!” warns a tongue-in-cheek piece that ran in the 1893 St. Johns Herald.[13]

Candy heart couldn’t have scared early Arizona residents too much – over a hundred years later, Halloween is a ten billion dollar industry that sees 600 million pounds of candy change hands annually. Trick or treat indeed!

Picture Captions:

Halloween Banner Photo: Photo by Charles Parker via Pexels.

Halloween Costume Party: A 1902 photograph of a costume party similar to the one held in Phoenix in 1898. Photo By National Library of Ireland on The Commons via Wikimedia Commons.

Chocolate Bar Wrapper: An early Hershey’s bar wrapper—the candy was first commercially available in about 1900. Photo by Hershey Company via Wikimedia Commons.

Endnotes:

[1] Martin, Emily. “The History of Trick-or-Treating, and How it Became a Halloween Tradition.” National Geographic, 23 Oct. 2022, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/the-history-of-trick-or-treating-and-how-it-became-a-halloween-tradition

[2] “Halloween Social.” Arizona Republican. (Phoenix, Ariz.) 02 Nov. 1893. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84020558/1893-11-02/ed-1/seq-5/

[3] “Society.” Arizona Republican. (Phoenix, Ariz.) 06 Nov. 1898. Newspapers.com. https://www.newspapers.com/image/119161736/

[4] “Youthful Pranks.” Arizona Republican. (Phoenix, Ariz.) 02 Nov. 1895. Newspapers.com. https://www.newspapers.com/image/119081013

[5] “News in a Nutshell.” Arizona Republican. (Phoenix, Ariz.) 02 Nov. 1895. Newspapers.com. https://www.newspapers.com/image/168475315/

[6] “Halloween Prank is Fatal to Douglas Boy—Is Shot by a Woman.” Bisbee Daily Review. (Bisbee, Ariz.), 01 Nov. 1913. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84024827/1913-11-01/ed-1/seq-1/

[7] “Enters Guilty Plea.” Arizona Republican. (Phoenix, Ariz.) 21 Feb. 1914. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84020558/1914-02-21/ed-1/seq-14/

[8] Bannatyne, Lesley. “When Halloween Was All Tricks and No Treats.” Smithsonian Magazine, 27 Oct. 2017, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/when-halloween-was-all-tricks-no-treats-180966996/

[9] Woellert, Dann. Cincinnati Candy: A Sweet History. Arcadia Publishing, 2017.

[10] Smith, Andrew. Food and Drink in American History. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2013.

[11] Chu, Anita. Field Guide to Candy: How to Identify and Make Virtually Every Candy Imaginable. Quirk Books, 2014.

[12] D’Antonio, Michael. Hershey: Milton S. Hershey’s Extraordinary Life of Wealth, Empire, and Utopian Dreams. Simon & Schuster, 2007.

[13] “Candy Heart.” The St Johns Herald. (St. Johns, Ariz.) 23 March 1893. Newspapers.com. https://www.newspapers.com/image/42326098/

Archive

-

2024

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-