After (my) first mouthful the tears started to come. I could not say a word and I believed I had hell-fire in my mouth.- Father Ignaz Pfefferkorn, 1794

Spicing it Up

Did you know…

We’ve all heard the metaphor, “As American as apple pie.” But apples and pie came to the Americas from Europe, not the other way around. What it should say is, “As American as chiles and chocolate!” After all, no one outside of the Americas was able to enjoy either of those tasty treats until they were exported from the New World into the Old. Today we’re here to talk about the former of the two – chiles.

Whether you prefer your chiles on the bell pepper end of the Scoville hotness scale (they rank at zero), or you’re crazy enough to brave a ghost pepper on the opposite end (coming in at 1,000,000+!), or even if your tastes rank somewhere in the middle (FYI – jalapeños come in at 2,500-8,000 units), humans have used chiles to spice up their food for thousands of years.

Wild Chiltepins, Arizona’s original chile pepper.

Remnants of chiles dating back 9,000 years have been found at archaeological excavations in Mexico, where the Mayans and Aztecs both consumed chiles, as did the Incas further south. When the Spanish came to the Americas, they found that chiles were a big part of the culture of the indigenous populations. In what is now Arizona, the ancient Sonoran peoples had a tradition of using chiles – both wild chiltepin (the only pepper native to AZ), as well as chiles likely traded for with peoples further south.

As Europeans moved into the Sonoran Desert, they found many unfamiliar foods on the menu, including beans, corn, squash, agave, and chiles. The newcomers may or may not have appreciated any of the rest of these, but they seem to have had a love/hate relationship with the chiles. A Jesuit missionary named Father Ignaz Pfefferkorn (b.1726-d.1798) wrote a two volume work about his life in the Sonoran Desert, including the foods eaten here at that time. A native German, he had this to say about chiles:

“The Spanish pepper, which is called chile in America, is abundantly grown in Sonora…Americans make of the Spanish pepper a sauce, which one could call the universal sauce because it must serve on and for everything…The same sauce serves for boiled fish and baked eggs but is only poured on them after they have been cooked. No dish is more agreeable to an American, but to a foreigner it is intolerable, especially at first, because of the monotonous hotness of the peppers.”

Father Pfefferkorn wasn’t the only European visitor to try and dislike chiles. An article from the Arizona Sentinel on December 14, 1872 reported upon eating chiles at the local Christmas-time festival, “When it comes to red peppers, seasoned with but very little, if any, meat, we ‘ain’t on it’.” So much for chiles!

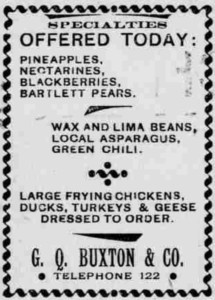

So how did hatred of chiles turn to love for the newcomers? The good Father reported that after having been burned multiple times by the spicy food, he eventually came to tolerate and even appreciate chiles. This must have been the case for many. By the early 1890s (if not before), stores like G. Q. Buxton & Co. and Ewell’s Grocery Co. sold green chiles and red chili sauce, restaurants like the Chop House sold enchiladas and other spicy Mexican food staples, and the April 22, 1891 AZ Republican touted a Mexican food booth at the Catholic Festival that served enchiladas, tamales, tortillas, and chile con carne. Yum!

So how did hatred of chiles turn to love for the newcomers? The good Father reported that after having been burned multiple times by the spicy food, he eventually came to tolerate and even appreciate chiles. This must have been the case for many. By the early 1890s (if not before), stores like G. Q. Buxton & Co. and Ewell’s Grocery Co. sold green chiles and red chili sauce, restaurants like the Chop House sold enchiladas and other spicy Mexican food staples, and the April 22, 1891 AZ Republican touted a Mexican food booth at the Catholic Festival that served enchiladas, tamales, tortillas, and chile con carne. Yum!

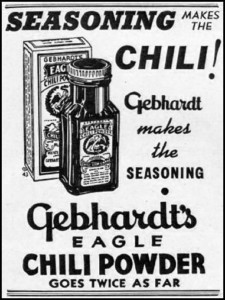

We happen to know that someone on Block 14 (now Heritage Square) liked to spice up their food, as a Gebhardt Eagle chili powder bottle was found here during restoration. (see it in the main picture above – it’s the bottle that is shown lying down). Interestingly enough, the Gebardt Chili Powder Co. was established in New Braunfels, TX in 1896 by William Gebhardt, another German immigrant who lived in the Southwest. He imported ancho chile peppers from San Luis Potosí, Mexico, dried them and ground them into a powder he first called, “Tampico Dust.” In 1908 he wrote a cookbook, called Mexican Cooking, to give people more recipes that used his chile powder. Note – the cookbook has recipes for anything he thought would taste good with a spicy kick, from spaghetti to potato salad, neither of which are traditional Mexican food. But it also includes recipes for chile rellenos, enchiladas, and other Mexican food staples.

More recently, an Arizona farmer had a lasting impact on chiles here in the US. Ed Curry of the Curry Seed & Chile Company (Pearce, AZ) developed a pepper in 1980 known as Arizona 20, which is now the standard of red and green chile peppers in the United States. Genetically, 80%-90% of all chiles grown in the US can be traced back to his farm (even in Hatch, NM!). He was also added to the Guinness Book of World Records in 2009 for growing the heaviest pepper in the world at 0.063 lbs. Not bad for this original American food!

More recently, an Arizona farmer had a lasting impact on chiles here in the US. Ed Curry of the Curry Seed & Chile Company (Pearce, AZ) developed a pepper in 1980 known as Arizona 20, which is now the standard of red and green chile peppers in the United States. Genetically, 80%-90% of all chiles grown in the US can be traced back to his farm (even in Hatch, NM!). He was also added to the Guinness Book of World Records in 2009 for growing the heaviest pepper in the world at 0.063 lbs. Not bad for this original American food!

To learn more about Father Pfeffercorn and Sonoran foodways, listen to this great podcast by Laura Carlson on The Feast: Meals that Made History. They also have many more excellent episodes, including one recorded right here at the Square!

Learn more about the Gebhardt Chili Powder Co. here, and about Ed Curry’s tasty Arizona chiles here.

Information for this article was found at the links listed above, as well as from the following sources: “Chiles: A Gift from a Fiery God,” by Paul W. Bosland, Agronomy and Horticulture Department, New Mexico State University, 1999; Sonora: A Description of the Province, Vol. 1, by Father Ignaz Pfefferkorn, 1794.