“When a baby over 10 pounds can be sent by parcel post for 15 cents, it looks as though the time (has) arrived for the stork to seek another job.”– Arizona Republican, February 2, 1913

Precious Parcels

Posted December 1, 2023

Written by Heather Roberts, Research Historian

For a printable version of this article, please click here.

Did you know…

It’s that time of year when post office workers and delivery drivers are kept busy with packages for holiday gift giving. And that handcrafted present Great Aunt Ida sent you might seem like the strangest thing ever shipped via the US Postal Service, but we can beat that with something that was a trend just over a century ago – mailing kids.

It’s that time of year when post office workers and delivery drivers are kept busy with packages for holiday gift giving. And that handcrafted present Great Aunt Ida sent you might seem like the strangest thing ever shipped via the US Postal Service, but we can beat that with something that was a trend just over a century ago – mailing kids.

You read that right! We’re not talking about baby goats here, but actual human children. We’ve discussed people having things shipped from mail-order catalogs at the turn of the 20th century – and most of those items would have had to been picked up at the train station by the people who ordered them – but now we’re talking about a gap in the US Postal Service (USPS) Parcel Post rules that parents exploited by sending their young children and babies to relatives living miles away through the mail on a wagon for local delivery (and sometimes, though rarely, in an automobile) or via the mail car on a train.

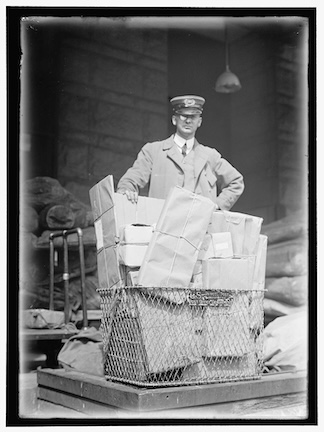

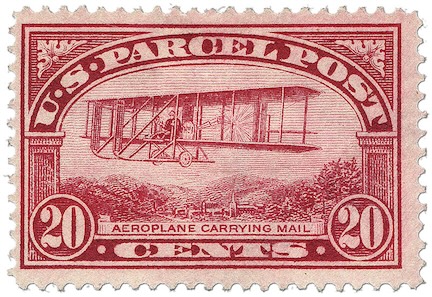

Until 1913, the USPS could only ship packages that were four pounds or less, with private companies handling larger packages. Private shipping was complicated and rates were expensive, leading to people calling for a cheaper and easier alternative. The postal service, who had only begun free home delivery to rural addresses nationwide in 1902 (urban areas were given that privilege beginning in 1863), asked to expand their operations and in August of 1912, Congress approved creation of the Parcel Post – USPS shipment of packages up to 11 lbs. (later changed to 20 lbs. and then 70 lbs.). At the end of the year, newspapers nationwide (like The Arvada Enterprise) published an official Parcel Post Map and rates of postage, along with an explanation of the new service that would begin on January 1, 1913.

It was an immediate success. The USPS reported that over three million packages were sent in the first six months of Parcel Post delivery. Two of the packages sent just after midnight on New Year’s Day were to President Taft (58 engraved and enameled silver spoons, one for each US state and territory) and President-elect Wilson (eleven pounds of apples from his club at Princeton). According to the Weekly Journal Miner newspaper, some of the earliest parcels sent in Prescott, AZ contained laundry, shoes, household goods, mutton chops, fresh fish, motorcycle and automobile parts, a baby carriage, a violin, a 10 lb. sack of peanuts, 2 lbs. of butter, and a large shipment of very fresh skunk hides (phew!).  Local stores also promoted delivery of their goods throughout Arizona, including Goldberg Bros, Hanny’s, The New York Store, and Elvey & Hulett druggists. In 1917, a town in Utah shipped all the construction materials for their new bank using Parcel Post, including 15,000 bricks mailed by the Salt Lake Pressed Brick Company in 1,500 separate packages. (Note: It was due to these specific shipments that the USPS changed the rules to mandate no more than 200 lbs. of goods be shipped per person, per day. The Postmaster General said in his orders, “It is not the intent of the U.S. postal service that buildings be shipped through the mail.” Maybe Sears used a separate shipping service for their catalog homes!)

Local stores also promoted delivery of their goods throughout Arizona, including Goldberg Bros, Hanny’s, The New York Store, and Elvey & Hulett druggists. In 1917, a town in Utah shipped all the construction materials for their new bank using Parcel Post, including 15,000 bricks mailed by the Salt Lake Pressed Brick Company in 1,500 separate packages. (Note: It was due to these specific shipments that the USPS changed the rules to mandate no more than 200 lbs. of goods be shipped per person, per day. The Postmaster General said in his orders, “It is not the intent of the U.S. postal service that buildings be shipped through the mail.” Maybe Sears used a separate shipping service for their catalog homes!)

But brick buildings and skunk hides weren’t the only odd things people were sending through the mail. On January 17, 1913, the Arizona Republican newspaper mentioned a letter received by the Postmaster General that posed this question: “May I ask you what specific relations to use in wrapping so it (the baby) would…be allowed shipment by parcel post.” Two days later, the paper reported, “The status of babies with respect to the parcel post is yet to be determined. Babies are not included either in the list of articles or commodities which may be transmitted or in the list of barred articles.” But before the Postmaster General could decide one way or the other about transporting children, a mailman in Ohio made the decision for him:

“V. O. Lyttle, a rural mail carrier was the first to accept and deliver under the parcel post a live baby. It was the infant of Mr. and Mrs. Jesse Beagle, of near Glen Este. The ‘package’ was well wrapped and ready for ‘mailing’ when the carrier got it today. Lyttle delivered the parcel safely to the address shown on a card attached, the home of its grandmother, Mrs. Louis Beagle, who lives about one mile from its home. Postage of fifteen cents was collected and the ‘parcel’ was insured for fifty dollars.” – Arizona Republican, January 26, 1913

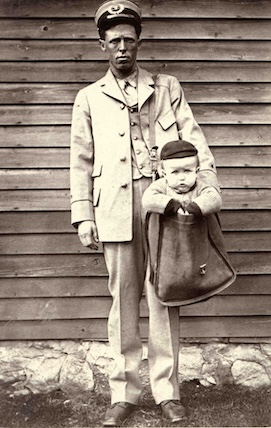

A staged photo of a baby in a letter carrier’s mailbag, Smithsonian Institution.

The Beagles’ baby wasn’t the only one shipped off to a relative’s house via Parcel Post, despite a rule being set in early 1914 against mailing babies. Between 1913 and 1920, we found 31 instances of children being shipped through the postal service, and there are likely more we missed or that weren’t mentioned in the newspapers. Here are a few of the more notable stories:

-

-

- Mail carrier Edgar F. Phillips of Ulmers, SC was delivering two infants and a wooden leg along his route when they were attacked by a wild cat. He was able to fend off the feline with the wooden leg, and delivered everything and everyone safely to their destination. (The Bamberg Herald, February 13, 1913)

- A 4 lb. baby was shipped to Dr. Moore of Greenville, KY from a Mrs. Bernard of New Orleans, LA. The doctor had recently been working at Tulane University in New Orleans, and the newspaper speculated that the doctor’s abilities had impressed the baby’s parents, so they sent the baby to him in Kentucky for treatment. (The Record, March 20, 1913)

- Eight-year-old Julia Kohan was sent to her father in New Lexington, OH by New York immigration officials after she traveled over 7,000 miles on her own from Bavaria (Germany) to the US. (The Mountain Democrat & Placerville Times, December 5, 1913)

- Bachelor Austin Bassett of New York, CA received a baby in the mail via parcel post from Seattle, WA. The newspaper reported that, “he is ignorant of the mother of the child, and is advertising her to put a stamp on herself and follow the baby.” (The Snowflake Herald, July 9, 1915)

- Six-year-old Audray Lenore Christy arrived in Phoenix via parcel post from Los Angeles, having enjoyed the trip but disliking “those ugly tags (i.e. – the postage stamps) on (her) dress and sweater”. (The Coconino Sun, October 31, 1919)

-

-

In the Spotlight

Mailing kids via Parcel Post was so ingrained in popular culture that several playful photos were staged of mail carriers with babies, like those we’ve shared here. There was also at least one play about it, and even a film made by Thomas Edison’s motion picture company! We found an ad for, “The Edison comedy hit, ‘By Parcel Post: How to Ship the Baby’” at the Royal Theatre in the Bisbee Daily Review (January 31, 1915). Unfortunately, we can’t find the film itself anywhere – but if we do find it, you know we’ll share it here.

Mailing kids via Parcel Post was so ingrained in popular culture that several playful photos were staged of mail carriers with babies, like those we’ve shared here. There was also at least one play about it, and even a film made by Thomas Edison’s motion picture company! We found an ad for, “The Edison comedy hit, ‘By Parcel Post: How to Ship the Baby’” at the Royal Theatre in the Bisbee Daily Review (January 31, 1915). Unfortunately, we can’t find the film itself anywhere – but if we do find it, you know we’ll share it here.The play tells the story of a hapless postman and the baby he was supposed to deliver, called “Barred from the Mails”. There’s a short summary of it in The Daily Missoulian (May 26, 1913). It’s a cute story, and worth a read.

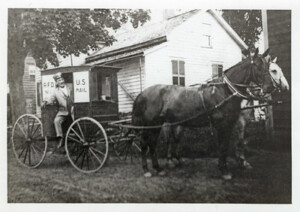

Why did the parents do it, though? Shipping a child sounds so dangerous! First, it’s important to remember that these were different times. People were more trusting overall, and children (particularly those from poorer families) were expected to be more self-reliant than we would expect them to be today. But many of these trips were relatively local, and mail carriers were well-known and trusted throughout the community. For a family who didn’t have access to reliable transportation, even for a trip of a few miles, handing their child off to someone who did would be a quick and easy solution to getting the kid to grandma’s. Even postal employees themselves used this shipping method – Robert Miller was sent by his mother, the Postmistress of Gackle, ND, 82 miles to Lisbon, ND to visit relatives; the Olympia, WA Assistant Postmaster and his wife sent their toddler to a relative 60 miles away after she (the mom) fell ill; and 5-year-old May Pierstorff was shipped 70 miles from Grangeville, ID to Lewiston, ID via a route on which her uncle was a mail clerk.

A mail carrier on his Rural Free Delivery route, circa 1900, Smithsonian.

Cost was a big factor for longer trips, as train fare was simply more expensive. For example, for the girl who was sent from Los Angeles to Phoenix, a round trip train ticket would have cost around $25, and her one-way transportation via parcel post, though not listed in the newspaper articles about her trip, likely cost between 50 cents and a dollar. Cost of shipping a child depended on the discretion of the postal employee, though – in one story, a 6-year-old girl was shipped over 700 miles from Pensacola, Florida to Christiansburg, VA at the cost of 15 cents. (We haven’t yet found record of what train fare would cost for that route, but think it could have been anything between $15 and $35.) For the postage costs mentioned in newspapers – and we found 13 cases in which costs were listed – the cheapest postage was free (for a 10-month-old baby who traveled 8 miles from Elmhurst, CA to Hayward, CA), and the most expensive was 78 cents (for a 13-year-old who traveled 96 miles from Cincinnati, OH to Versailles, OH).

In June 1920, the Post Office Department officially ruled that children could no longer be allowed to be shipped via Parcel Post, as they could not, “be classified as harmless live animals that do not require food or water.” In the years that followed, the only mention of babies and Parcel Post was in regards to baby chicks being sent through the service in spring (El Paso Herald, June 29, 1920, amongst others), mothers being allowed to weigh their babies on the Parcel Post scales to track their development (Carrizozo Outlook, September 2, 1921, amongst others), and a story of two baby ostriches being shipped across the US from Florida to Washington state (Evening Star, July 22, 1922).

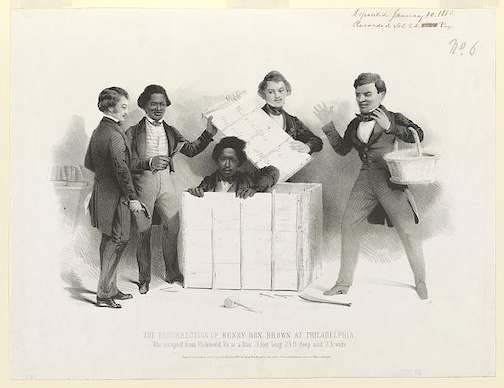

Though these stories of parents mailing their kids are a fascinating glimpse into a different time, the most compelling story of someone being shipped via mail is that of Henry “Box” Brown. Separated from his parents and siblings and then later his wife and children by the horrors of slavery, Henry got the idea to ship himself in a crate to freedom. With the help of a local storekeeper, on March 29, 1849, he was secured in a wooden crate that was 3 feet long, 2.5 feet high, and 2 feet wide. Cramped in the box, he traveled from Richmond, VA to Philadelphia, PA via wagon, train car, and steamboat, crossing 350 miles over the next 27 hours.Though they gave instructions that the box needed to be kept upright, it was stacked incorrectly twice, and for one stretch Henry was forced to remain upside down almost an hour and a half. He’s quoted as saying, “I felt my eyes swelling as if they would burst from their sockets; and the veins on my temples were dreadfully distended with pressure of blood upon my head.” When his box was opened in Philadelphia, he was alive, though weak. After he recovered, Henry traveled to Anti-Slavery meetings throughout the Northeast.

But though he was free, Henry wasn’t safe in an America that, less than a year after his dangerous trip, declared it was illegal to help people escape slavery (Fugitive Slave Act, 1850). He traveled under an assumed name and took asylum overseas in England, giving talks about his escape. Henry remarried and later came back to the US after the Civil War, but information about him online doesn’t reveal whether he ever saw any of his previously enslaved family again. You can see a contemporary monument honoring Henry “Box” Brown, located in Richmond, VA, and can also read Henry Brown’s autobiographical story of his escape – Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown by Henry Box Brown (1851).

But though he was free, Henry wasn’t safe in an America that, less than a year after his dangerous trip, declared it was illegal to help people escape slavery (Fugitive Slave Act, 1850). He traveled under an assumed name and took asylum overseas in England, giving talks about his escape. Henry remarried and later came back to the US after the Civil War, but information about him online doesn’t reveal whether he ever saw any of his previously enslaved family again. You can see a contemporary monument honoring Henry “Box” Brown, located in Richmond, VA, and can also read Henry Brown’s autobiographical story of his escape – Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown by Henry Box Brown (1851).

One of the cruelest parts of slavery was the forcible separation of families. For decades after the Civil War, families tried to find one another with the help of organizations like the Freedman’s Bureau, but also simply by using newspaper ads, hoping someone would see them. You can search over 3,500 of these ads, spanning eight decades from 275 newspapers, from the digital project Last Seen: Finding Family After Slavery.

Learn more about mail-order catalogs, along with the various parts of Rosson House ordered via catalog by reading our blog articles – Mail-Order Hardware & Houses; Fancy Floors (parquet wood flooring); So Metal (pressed metal ceilings); A Glass Act (windows); Mail-Order Catalogues (a general history).

At the top of the page – Picture of a child in a box, edited. Original by Cottonbro studio via Pexels.

Lithograph at the bottom of the article – The “resurrection” of Henry “Box” Brown, circa 1850, Library of Congress.

Much of the information for this blog article was found online through the Library of Congress Chronicling America digital newspaper database, and also from Smithsonian National Postal Museum – The First Packages; Very Special Deliveries, Object Spotlight: Parcel Post Map, Precious Packages: America’s Parcel Post Service, The Oddest Parcels, Parcel Post Stamps; Smithsonian Libraries – Parcel Post: Delivery of Dreams; USPS – The Bank of Vernal: The “Parcel Post Bank” (PDF); Postal History: Rural Free Delivery; Universal Service and the Postal Monopoly: A Brief History; the Newspapers.com blog, Fishwrap – Special Delivery: Children Sent Through Parcel Post; ThoughtCo – When it was Legal to Mail a Baby; Mental Floss – Six Bizarre Items Mailed Through the US Postal System; Virginia Museum of History & Culture – The Resurrection of Henry “Box” Brown; New Bedford Whaling National Historic Park – Henry ‘Box’ Brown; and Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown by Henry Box Brown (1851).

Archive

-

2024

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-