“Let me suggest that every one who creates or cultivates a garden helps, and greatly, to solve the problem of the feeding of the nations.”- Woodrow Wilson, 1917

Victory Gardens

For a printable version of this article, please click here.

Did you know…

From interviews with former Rosson House residents Jesse Jean (Higley) Lane and Georgie (Gammel) Valliere, we know just a little bit about what the land around Rosson House looked like when their families lived here. Jesse Jean talked about rose gardens and fruit trees, and Georgia about an enormous grapefruit tree on the south side of the House. The few pictures we have of the House from when the families lived there show palms or palm trees, along with citrus and other deciduous trees, and a vine growing along the south side of the front porch. However, what we don’t know is if any of the families who lived at Rosson House kept a vegetable garden. None of the interviews, period maps, or restoration notes mention household gardens, but if we had to guess, we’d say the Gammel family, who lived at Rosson House from 1914-1948, were very likely to have had not just a vegetable garden, but a Victory Garden.

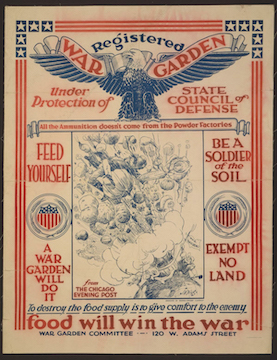

The first Victory Gardens were started during World War I, and were at that time called War Gardens or Liberty Gardens. Almost three years into the war, critical food shortages were hitting Europe hard. In March 1917, just weeks before the US entered the war themselves, the National War Garden Commission was independently organized by Charles Lathrop Pack. It encouraged Americans to plant their own gardens so food from commercial farms could be sent to our allies in Europe, and later to our own troops there. It increased the amount of food available and reduced need to ship produce, opening up railroad lines and ships to transport war materials instead. The US Food Administration was established on August 10, 1917 to coordinate the wartime food inventory, along with the conservation, transportation, and distribution of food. The US School Garden Army (USSGA) and the Women’s Land Army (WLA) were also established in 1917, giving everyone the chance to contribute to the war effort on the Home Front. Posters, signs along highways , ads in newspapers, seed catalogs, and even a special “Win the War in the Kitchen” cookbook were part of a larger campaign to get the word out – gardening wasn’t just practical, it was patriotic. Along with many other newspapers, ads in The Phoenix Tribune promoted War Gardens and war bonds together as ways to support the war effort. A reported 3.5 million Liberty Gardens were planted in 1917, with a total of 5.2 million by the end of the war in 1918. With these efforts, the US became the world’s largest seed supplier and was able to double food exports to Europe within a year.

The first Victory Gardens were started during World War I, and were at that time called War Gardens or Liberty Gardens. Almost three years into the war, critical food shortages were hitting Europe hard. In March 1917, just weeks before the US entered the war themselves, the National War Garden Commission was independently organized by Charles Lathrop Pack. It encouraged Americans to plant their own gardens so food from commercial farms could be sent to our allies in Europe, and later to our own troops there. It increased the amount of food available and reduced need to ship produce, opening up railroad lines and ships to transport war materials instead. The US Food Administration was established on August 10, 1917 to coordinate the wartime food inventory, along with the conservation, transportation, and distribution of food. The US School Garden Army (USSGA) and the Women’s Land Army (WLA) were also established in 1917, giving everyone the chance to contribute to the war effort on the Home Front. Posters, signs along highways , ads in newspapers, seed catalogs, and even a special “Win the War in the Kitchen” cookbook were part of a larger campaign to get the word out – gardening wasn’t just practical, it was patriotic. Along with many other newspapers, ads in The Phoenix Tribune promoted War Gardens and war bonds together as ways to support the war effort. A reported 3.5 million Liberty Gardens were planted in 1917, with a total of 5.2 million by the end of the war in 1918. With these efforts, the US became the world’s largest seed supplier and was able to double food exports to Europe within a year.

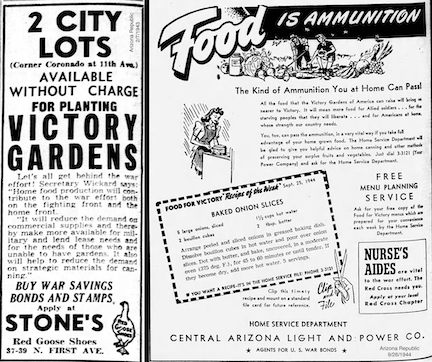

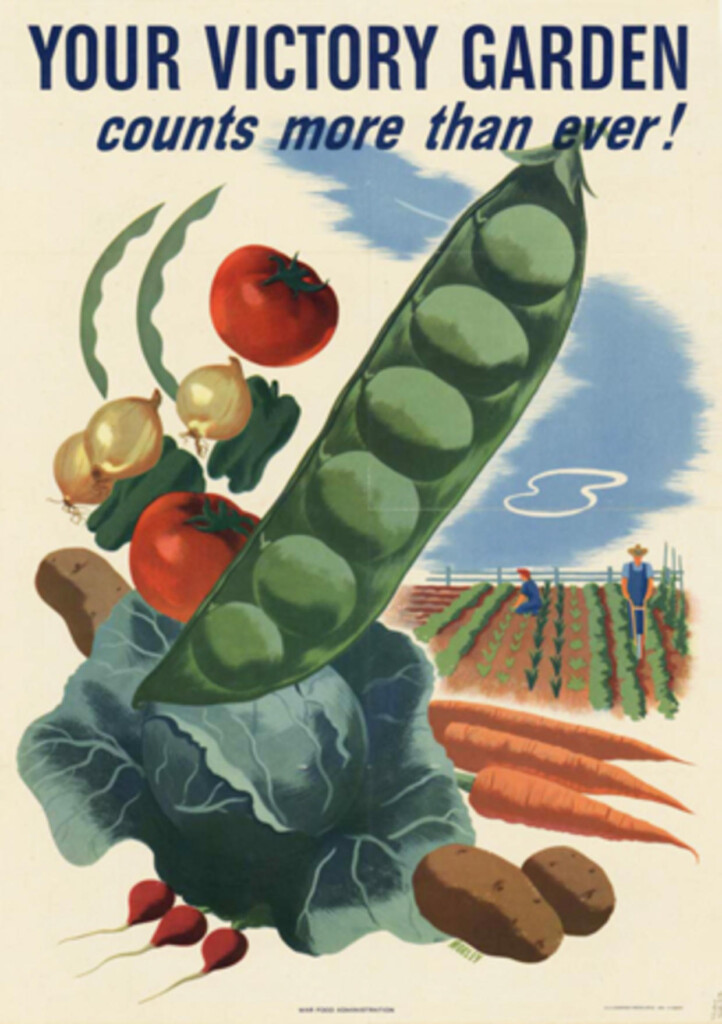

Under the Lend – Lease agreement, the United States was already providing Great Britain with food and materials prior to entering the war on December 8, 1941, the day after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. In January 1942, the Office of Civilian Defense announced that it would initiate a Victory Garden program, similar to those started during World War I. But Secretary of Agriculture, Claude Wickard, had a caveat – he believed that food production needed to increase, but that the World War I Liberty Gardens had been unnecessary and that all seeds, fertilizers, etc. should be saved for farming professionals. By 1943, however, he changed his mind, saying, “Victory gardens offer those on the home front a chance to get in the battle of food.” Why the change of heart? The US had been at war for over a year, with no end in sight. More food was being rationed, and some cities and states had started their own successful Victory Garden programs in lieu of federal support. Ads promoting Victory Gardens started popping up in Arizona newspapers in 1942, regardless of what the Secretary of Agriculture thought. Businesses that had nothing to do with gardening, farming, food, or land encouraged people to start Victory Gardens – giving out booklets on how to start a garden as well as cookbooks and menu plans that featured home grown produce, and advertising vacant lots of land available for cultivation. The classified section of the newspaper listing houses for sale or lease included Victory Gardens in their descriptions. Eleanor Roosevelt started her own Victory Garden at the White House in 1943, growing beans, carrots, tomatoes, and cabbages. Even Hollywood got in on the act (see below), making short films to play between features that promoted planting Victory Gardens. By 1944, an estimated 18-20 million US families had Victory Gardens, providing 8 million tons of produce that year (approximately 40% of all US production).

Under the Lend – Lease agreement, the United States was already providing Great Britain with food and materials prior to entering the war on December 8, 1941, the day after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. In January 1942, the Office of Civilian Defense announced that it would initiate a Victory Garden program, similar to those started during World War I. But Secretary of Agriculture, Claude Wickard, had a caveat – he believed that food production needed to increase, but that the World War I Liberty Gardens had been unnecessary and that all seeds, fertilizers, etc. should be saved for farming professionals. By 1943, however, he changed his mind, saying, “Victory gardens offer those on the home front a chance to get in the battle of food.” Why the change of heart? The US had been at war for over a year, with no end in sight. More food was being rationed, and some cities and states had started their own successful Victory Garden programs in lieu of federal support. Ads promoting Victory Gardens started popping up in Arizona newspapers in 1942, regardless of what the Secretary of Agriculture thought. Businesses that had nothing to do with gardening, farming, food, or land encouraged people to start Victory Gardens – giving out booklets on how to start a garden as well as cookbooks and menu plans that featured home grown produce, and advertising vacant lots of land available for cultivation. The classified section of the newspaper listing houses for sale or lease included Victory Gardens in their descriptions. Eleanor Roosevelt started her own Victory Garden at the White House in 1943, growing beans, carrots, tomatoes, and cabbages. Even Hollywood got in on the act (see below), making short films to play between features that promoted planting Victory Gardens. By 1944, an estimated 18-20 million US families had Victory Gardens, providing 8 million tons of produce that year (approximately 40% of all US production).

-

The Gardens of Victory

See this World War II short film about the importance of Victory Gardens, made by the US Office of Civilian Defense and sponsored by Better Homes and Gardens magazine.

War isn’t the only time in US history that people have gardened as part of a public program. During economic downturns, people have come together to create gardens for their communities. Communal gardens were set up in urban areas like Detroit, New York, and Philadelphia during the 1890s depression (1893-1897) by local Vacant Lots Cultivation Associations. Thrift or Relief gardens were created during the Great Depression (1929-1939), and the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA, 1933-1935) distributed over $3 billion of aid in their work garden program, which paid people to grow and distribute produce to those in need. The Works Progress Administration funded community gardens here in Phoenix, including one 2 acre garden on south 12th Street. In between crises like economic depressions and world wars, some neighborhoods turned to community gardens as a way to fight against food insecurity and food deserts. African American communities who had Liberty Gardens during World War I continued their local gardening efforts before and into the Depression years, improving the curb appeal of neighborhoods that had been long overlooked and neglected by municipalities due to racism. More recently, people turned to gardening during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, seeing benefits to their mental and physical health as well as to their stomachs. Many have found their vegetable gardens continue to be valuable due to the price of produce increasing because of inflation. And because home gardens tend to use less pesticides and their produce doesn’t need to be shipped, they’re better for the environment. It’s a win-win!

Main Picture: Sterrett School garden, September 10, 1917, courtesy of the Library of Congress

Learn about the gardens of the World War II Japanese American incarceration camps, including those here in Arizona, from the Densho Encyclopedia. Explore the US National Archives’ exhibit The US Food Administration, Women, and the Great War: The Pennsylvania Food Conservation Train.

Read more about food history from our previous blog articles: Can It! (about food preservation history); Spicing it Up (about the history of spicy food in Arizona); Bon Appétit (about the history of Victorian dining); Victorian Food à la 1977 (copy of a speech given by Eugene Parker of the Associated Grocers, to attendees of the Phoenix History Conference on October 15, 1977, about the Phoenix food industry in 1895).

Information for this article was found in The Phoenix Tribune (1918) and the Arizona Republic (1917-1918, 1942-1945); Smithsonian Gardens Community of Gardens Grown from the Past; the NYC Dept of Records & Information Services Victory Gardens; Smithsonian Libraries Gardening for the Common Good; The City of Greeley Museums Food is Ammunition – Don’t Waste It, pt.1; Cayuga Museum of History & Art Patriotic Planting; Wessels Living History Farm Victory Gardens; The Huntington A Resurgence of Victory Gardens; Atlas Obscura “When WWII Started, the US Government Fought Against Victory Gardens”; Sidewalk Sprouts Depression Relief Gardens; History Food Rationing in Wartime America; Garden Pals Gardening Statistics in 2022.

Archive

-

2024

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-