America’s Pastime

Did you know…

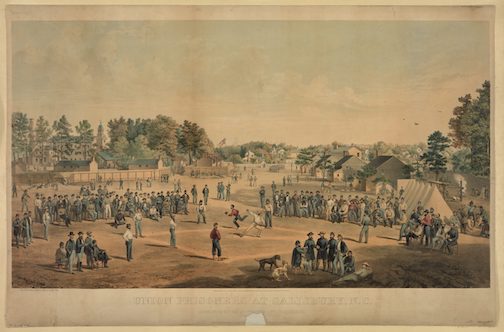

The baseball game pictured in this print was played at Salisbury Confederate Prison in North Carolina in 1862.

The weather is getting a little warmer in Arizona but the nights are still cool, and that means it’s that time of year where millions of people descend on Phoenix to enjoy watching grown men play a game that’s probably as old as our country is – baseball.

Americans began playing some form of the game as early as the 1700s in places like Massachusetts, Philadelphia, and New York, with each area having their own set of rules. Baseball as we know it today is more similar to the New York version, with a mandatory base running path and foul lines, instead of the Massachusetts version, where you could run wherever you wanted after hitting the ball. Baseball was played during the Civil War, with Union soldiers introducing the sport to soldiers from southern and western states and territories.

Miners and soldiers brought baseball with them to Arizona – they would form teams and play games when they weren’t working, and teams from both would frequently play each other in friendly contests. The earliest mention of the game we could find from local sources was in the Arizona Weekly Miner (Prescott), in 1875.

“At a base-ball game played at Camp McDowell, on New Year’s Day, between the Light-foot club, of the 8th Infantry, and the Shamrock club, of the 5th Calvary, the five innings resulted in a total score of 14 for the Light-foots and 10 for the Shamrocks.”

Newspapers often called for teams to be created locally. Rival newspapers in Tucson put together teams for a Thanksgiving Day match in 1879. The Phoenix Herald called for a team to play in the Phoenix town plaza that same year, the Weekly Arizona Citizen in Tucson asked readers to set up a local team in 1880 (citing the team from Phoenix as their main opponent), and the Tombstone Epitaph called for a team in 1882.

Towns all over the territory soon had teams, including Bisbee, AZ, who can lay claim to historic Warren Ballpark, the oldest continuously used ballpark in the US. Built in 1909 for local miners and their families, the park also welcomed traveling teams, and even hosted Major League exhibition games between the Cubs and White Sox.

The Gila Junior All-Stars, c.1944. ((Bill Staples Jr. / Nisei Baseball Research Project)

The story of baseball in Arizona is also one of perseverance under adversity. During World War II, two Japanese American internment camps were established in the state. At the Gila River Camp, internees constructed a baseball diamond (Zenimura Field) and played games against local teams and against internees from other camps. After the war, African American baseball players faced segregation and overt racism, even as baseball itself began to integrate. Players in Arizona (and across much of the country) could not stay in the same hotels as their white teammates, or use the same facilities, but that didn’t discourage them from playing. Both Japanese American and African American baseball players found the game to be an overall positive experience, encouraging a feeling of goodwill and humanity between the players and the local community.

“It was a game that most of us will never forget. I realized that these people were Americans, just like myself. The more I thought about it, the more I thought, what a big mistake we made by putting these people in this relocation camp.” -Bernie Weinstein, a player on the Tucson Badgers, who played the team from Gila River during the war.

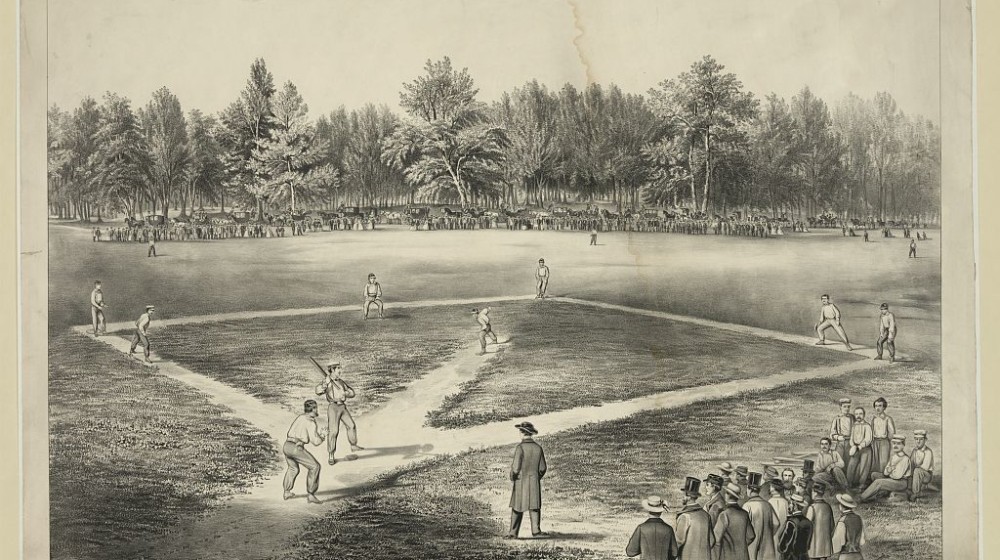

Information for this blog was found from these sources: The Secret History of Baseball’s Earliest Days (NPR); Civil War Baseball (National Museum of American History); Library of Congress Chronicling America digital newspaper archive (Weekly Arizona Citizen, Arizona Weekly Miner, Tombstone Epitaph, Phoenix Herald); When the Major Leagues Came to Warren Ballpark (My Herald Review); A Field of Dreams in the Arizona Desert (National Baseball Hall of Fame); Arizona an Early Outpost of Integration in the MLB (MLB.com). The picture at the top of the page is from Currier & Ives, c.1866 (courtesy of the Library of Congress archives).

Archive

-

2024

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-