Mail-Order Catalogues

Posted December 1, 2021

Written by Heather Roberts, Research Historian

For a printable version of this article, please click here.

Did you know…

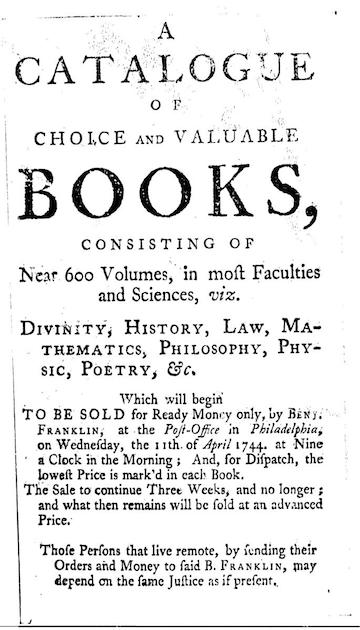

Ordering items through the mail has been popular for hundreds of years. Look at any newspaper in the late 18th century and throughout the 19th, and you’ll see that mail-order businesses were already flourishing long before mail-order catalogues were popular. And while eventually they would become incredibly commonplace by the time the Rosson House was built, Benjamin Franklin is credited with starting the first US mail-order catalogue in 1744 – actually a listing of books for sale that could be purchased and delivered through the mail without having to step foot in his print shop in Philadelphia.

Ordering items through the mail has been popular for hundreds of years. Look at any newspaper in the late 18th century and throughout the 19th, and you’ll see that mail-order businesses were already flourishing long before mail-order catalogues were popular. And while eventually they would become incredibly commonplace by the time the Rosson House was built, Benjamin Franklin is credited with starting the first US mail-order catalogue in 1744 – actually a listing of books for sale that could be purchased and delivered through the mail without having to step foot in his print shop in Philadelphia.

Mail-order and trade catalogues – that is, catalogues that were created as advertisements to sell goods at wholesale prices within industries, which would be ordered and shipped from afar – became very popular as the US population and economy grew, and the size of the middle class increased. But what really made catalogues work well was the expansion of the railroad and the postal service in the mid-1800s.

Railroads revolutionized travel and transportation of goods in the 19th century. In 1827, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad was approved as the first railway in the country to transport people and freight. Their journey was a whopping 13 miles. But by 1850, US railroads had over 9,000 miles of tracks. Work on the first transcontinental railroad was finished on May 10, 1869, connecting the two coasts together with nearly 2,000 miles of track. By 1900, four more set of transcontinental tracks spanned the country, allowing for far more efficient transportation of people and products.

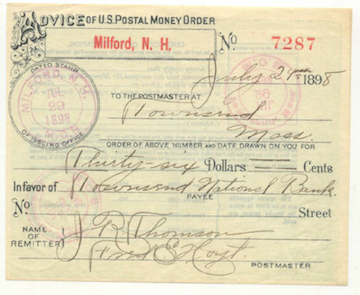

The US Post Office established a postal money order system in 1864, at that time allowing money to safely be sent to and from US soldiers during the Civil War. This was also a boon to mail-order businesses, who then had a safe way to get paid for their goods. That same year the railway mail system was developed – setting up a railcar that was essentially a working post office on trains that carried the mail. In these cars, postal employees would efficiently sort mail on the go as it came in. Previously mail had been unloaded at each stop, sorted with any new mail, and reloaded onto the train. Free rural delivery was finally authorized nation-wide in 1902, which made mail-order shipping that much easier.

-

Mail-Order Mansions

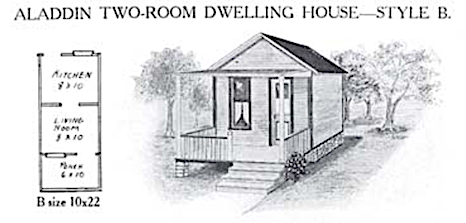

By 1906, people could order a complete house kit from a catalog instead of all of the parts individually. According to the 1909 catalog by Aladdin Houses, a kit would include blueprints like George Barber sold, and everything to finish the house in its entirety – all lumber cut to fit, joists, studding and rafters, siding, flooring, roofing, porch materials (timbers, columns, railing, steps), doors with trim, door locks and hinges, windows with sashes and trim, hardware and nails, plasterboard, baseboards, and enough paint for two coats of the interior and exterior of the house. It would also include a step-by-step manual for building the house. You’ll notice the list does not include plumbing or electrical wiring – their cheapest houses, two and three-room houses at or around 250 square feet, do not include bathrooms. By 1919, the company had a special booklet customers could order that included such extras as bathroom fixtures, electric lighting, and heating systems. Sears & Roebuck and Montgomery Ward (as Wardway Homes) also sold kit homes for many years, but their popularity waned in the 1930s due to the Great Depression.

By 1906, people could order a complete house kit from a catalog instead of all of the parts individually. According to the 1909 catalog by Aladdin Houses, a kit would include blueprints like George Barber sold, and everything to finish the house in its entirety – all lumber cut to fit, joists, studding and rafters, siding, flooring, roofing, porch materials (timbers, columns, railing, steps), doors with trim, door locks and hinges, windows with sashes and trim, hardware and nails, plasterboard, baseboards, and enough paint for two coats of the interior and exterior of the house. It would also include a step-by-step manual for building the house. You’ll notice the list does not include plumbing or electrical wiring – their cheapest houses, two and three-room houses at or around 250 square feet, do not include bathrooms. By 1919, the company had a special booklet customers could order that included such extras as bathroom fixtures, electric lighting, and heating systems. Sears & Roebuck and Montgomery Ward (as Wardway Homes) also sold kit homes for many years, but their popularity waned in the 1930s due to the Great Depression.

-

A Catalogue Connection

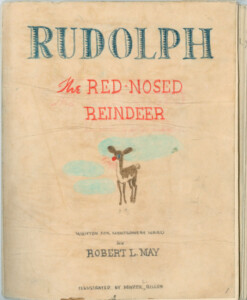

You can thank the Montgomery Ward catalogue for that famous holiday hero and misfit, Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. No, really!

You can thank the Montgomery Ward catalogue for that famous holiday hero and misfit, Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. No, really!Author Robert May was working as a catalogue writer for Montgomery Ward in 1939 when they asked him to write a children’s story to go along with their holiday coloring book. With a little help from his daughter, he came up with a story to, as they say, “Go down in history!”

Read more about the story on the WBUR/NPR website.

Though catalogues existed before Montgomery Ward & Co. and Sears, Roebuck & Co, these two were definitely the biggest. Both were selling goods of every kind within the same pages, from machinists’ tools and agricultural supplies to baby clothes and tea sets. Both were general merchandise catalogues operating out of Chicago, Illinois, and both built a reputation for cheap prices and a satisfaction guarantee. Montgomery Ward was the first of the two, distributing their 163-item catalogue in 1872. By 1897, Montgomery Ward had over a thousand employees, had become Chicago’s leading user of the US postal service, and their sales had exploded to about $7 million a year. The Sears & Roebuck catalogue didn’t come onto the scene until 1893, over 20 years later, but they weren’t slackers. By 1905 they employed around 9,000 people and were enjoying nearly $50 million in annual sales.

When it came time for the Rossons to build their beautiful house in the 1890s, they had their pick of construction materials from across the US. We know they chose their parquet wood flooring from the SC Johnson Wax catalogue (Racine, Wisconsin), and their door hardware from the Hibbard, Spencer, Bartlett & Co. catalogue (Chicago, Illinois). We also know they got their wallpaper from New York, and think they got their beveled, bay window from San Francisco, but we’re still looking for those catalogues.

Most of the things you’d find inside Rosson House could have been ordered via catalogue as well. The organ in the formal parlor can be found in the Chicago Cottage Organ Company’s 1890 catalogue, and you can browse Wooton desks like the one in the Rosson House doctor’s office from their 1876 trade catalogue. Bloomingdales sold Haviland china similar to the pattern we have in our collection in their 1890 catalogue, and the 1902 Sears & Roebuck catalogue has a prep table (called a kitchen cabinet) very similar to the one we have in the Rosson House kitchen.

To order something, customers had to fill out the order form found in their chosen catalogue, and follow the specific instructions for shipping. The Sears catalogue instructions were lengthy, but to be fair, it sounds like shipping was kind of complicated, and it was nice for them to try and work out all the kinks for their customers. Arizona was one of the more expensive places to ship items to (according to that catalogue), where the minimum freight charge came in between $2.71-$3.40 (Phoenix was $3.25, and Austin, Nevada, was the most expensive place to ship, at $4.32). Some items cost more to ship, and some less. Both Sears & Roebuck and Montgomery Ward encouraged people to get together with their friends, family, and/or neighbors, to buy in bulk and share the cost of shipping – kind of like going to Costco or Sam’s Club today!

Browse through catalogues we talked about in this article!

- Montgomery Ward (1875)

- Bloomingdale Bros. (1890)

- Wooten Desk Company (1876)

- Chicago Cottage Organ Co. (c1890)

- Hibbard, Spencer, Bartlett & Co. (1891) – Rosson House doorknobs are found on p304, which is p262 of the print catalogue

- S.C. Johnson & Son (1901): Ornamental Hardwood Floors

Browse through the Arizona Historical Society’s Railways of America Virtual Project for an in-depth look at over 150 years of railway history in Arizona. We love it!

Information for this article was found from: Our blog article Mail-Order Hardware & Houses (though many of our articles reference turn-of-the-century catalogues); National Museum of American History – Delivering the Goods; Smithsonian National Postal Museum – Money Orders; History of the Sears Catalog; Atlas Obscura: How Sears and Montgomery Ward Changed American Shipping; Library of Congress – Railroads in the Late 19th Century, and Completion of the Transcontinental Railroad; Harvard Business School – Trade Catalogs; Encyclopedia of Chicago – Mail Order.

Archive

-

2024

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-