Votes for Women

Did you know…

This year were are celebrating the centennial of the 19th Amendment, recognizing that all US citizens have the right to vote, regardless of their gender. Arizona recognized this right eight years prior, with their vote in the November 1912 election enacting an amendment to the state constitution that guaranteed women the right to vote (Votes For 13,442 / 68.43%; Votes Against 6,202 / 31.57%). Arizona was one of the first states to ratify the 19th Amendment, in February 1920. Tennessee was the 36th to do so (on August 18, 1920), which gave the Amendment the majority it needed to become law. Mississippi was the last state to do so, very belatedly, on March 22, 1984.

We don’t know how the men from Heritage Square voted on the 1912 Arizona ballot measure, nor how they or the women from Heritage Square felt about it (though, boy, do we wish we knew, and we will definitely keep looking!). But we have been able to find voter registrations for many of the women who lived there. Carrie Goldberg (41), Selma Goldberg (21), Hazel Melczer/Goldberg (23), Jessie Howe Higley (51), Frankie Gammel (33), and Mary J. Silva (45) all registered to vote in April 1913, in what was likely the one of the first waves of women voters registered in this state. Jessie Jean Higley (23) registered to vote in 1918, Eliza Teeter (43) in 1914, Josephine Silva (25) in 1926, Kathryn Baird (43) in 1928, and Wilma Tayrien/Gammel (24) in 1932. The state amendment passed while the Higleys lived at Rosson House, and Mrs. Higley was the first woman to register to vote while living there.

We don’t know how the men from Heritage Square voted on the 1912 Arizona ballot measure, nor how they or the women from Heritage Square felt about it (though, boy, do we wish we knew, and we will definitely keep looking!). But we have been able to find voter registrations for many of the women who lived there. Carrie Goldberg (41), Selma Goldberg (21), Hazel Melczer/Goldberg (23), Jessie Howe Higley (51), Frankie Gammel (33), and Mary J. Silva (45) all registered to vote in April 1913, in what was likely the one of the first waves of women voters registered in this state. Jessie Jean Higley (23) registered to vote in 1918, Eliza Teeter (43) in 1914, Josephine Silva (25) in 1926, Kathryn Baird (43) in 1928, and Wilma Tayrien/Gammel (24) in 1932. The state amendment passed while the Higleys lived at Rosson House, and Mrs. Higley was the first woman to register to vote while living there.

So far, we haven’t found any voter registration information for Constance Stevens, Anna or Marguerite Haustgen, Annie Ponder/Gammel, Georgia Valliere/Sewell/Gammel, or any of Flora Rosson’s daughters. Flora Rosson herself never got the opportunity to vote – she died at the age of 52, one month and a day before women’s suffrage was recognized in her home of California. Also absent from voter registration records is Mary Johns, the Native American woman listed in the 1910 census as a live-in servant of the Higley family (who were living at Rosson House at that time).

Neglecting to find voter registration information isn’t always because it doesn’t exist. Unreadable handwriting and differences in spelling can create mistakes in online records. Records can also be lost, or not kept for whatever reason. It’s possible that most of these women did register to vote (some of them earlier than in the records we found), and that we will eventually find those records. It’s probable, though, that Mary Johns may have never had the opportunity to vote. Why is this?

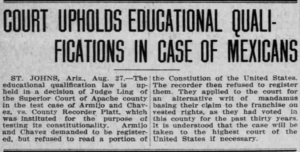

The Copper Era newspaper, August 30, 1912

First of all, Native Americans weren’t even considered to be US citizens until 1924, so that means that Mary Johns couldn’t have voted when women’s suffrage became legal in Arizona in 1912, or in the US in 1920. Secondly, until 1948, Arizona law prohibited Native Americans who lived on reservations from voting, claiming that because residents there were under tribal jurisdiction instead of US jurisdiction, and because those Native Americans didn’t pay state property tax, they didn’t have the right to vote. And thirdly, there were laws in effect here and in many other states that made it more difficult for Native Americans, non-English speaking Americans, immigrants, and the poor to be able to vote. This included an Arizona territorial poll tax of $3 (1865-1901), and a literacy test that involved reading the US Constitution in English. Residency requirements, bans on naturalization (like the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882), gerrymandering, requiring specific types of voter IDs, and not having ballot boxes and/or polling places in areas near and/or convenient to voters have also been used to disenfranchise people. (Read about Agnes Laughter, a Navajo woman who had to fight for the right to vote here in Arizona for most of her life.)

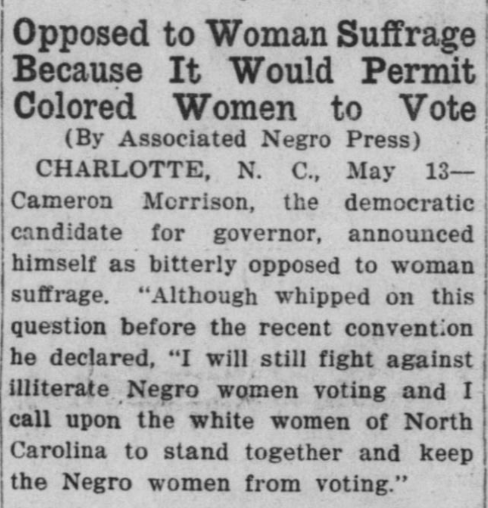

Like Mary Johns, many other women in the United States weren’t able to vote immediately after women’s suffrage became law in 1920. In Georgia, Mississippi, Arkansas, and South Carolina, for example, state legislatures enacted laws that said voters who first registered less than 6 months prior to an election could not vote in that election. This meant that all the women who registered to vote in those states after suffrage was passed in August 1920 could not vote in the November election. Poll taxes were still legal at that time, and some families could not afford to pay the tax for both husband and wife. In several southern states, only white women were encouraged to register to vote – under segregation they specifically hired more registrars for white women, and not enough for African American women (and sometimes none at all).

Phoenix Tribune newspaper, May 14, 1920

Intimidation and violence were often used to prevent those few who did register to vote from exercising their rights. Read more about the struggle of African American suffragists in this article from the National Park Service.

Estimated voter turnout for the1920 election was 36% for available women voters, and 68% for men. Since 1980, however, women have outnumbered men as registered voters and in voter turnout.

Voting is an important way we exercise our constitutional rights as citizens. In Arizona you can register to vote online, check to make sure your voter registration is current, and sign up for an absentee ballot and more at www.arizona.vote.

Read more about women’s suffrage in Arizona in these articles from the National Park Service and from Arizona PBS.

Information for this blog was found in Arizona Voter Registration Records (Ancestry.com); in the Library of Congress and Arizona Memory Project newspaper archives; on History.com and Ballotpedia.org; from the Washington Post and Smithsonian Magazine; and from the Center for American Women and Politics.

Archive

-

2024

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-