“One of the most excellent of recent innovations is the introduction of metal ceilings in place of wood and plaster. These ceilings do not shrink or burn like wood; they will not stain, crack or fall off like plaster, but being permanent, durable, fireproof and ornamental, will eventually supersede both wood and plaster, besides being in the end far more economical than either.” – Ad in the Arizona Silver Belt newspaper, Globe City, AZ, 01/10/1891

So Metal

For a printable version of this article, please click here.

Did you know…

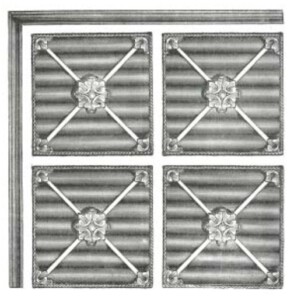

An illustration of a metal ceiling from the 1872 Philadelphia Architectural Iron Company trade catalog.

The next time you visit Rosson House, make sure you look up! Unlike those in our modern homes, the ceilings at Rosson House are definitely worth a second glance. Made of pressed steel, these kinds of ceilings were created in the late 19th century as a cheaper alternative to the decorative plaster and carved wood ceilings that were popular with wealthier Americans beginning a century earlier. The plaster and wood ceilings were more expensive because specially trained craftsmen had to be hired for the detail work, and the upkeep as the ceilings aged could be costly. In contrast, three of the top selling points in nearly every ornamental metal ceiling catalog we looked at were: How inexpensive they were, how easy they were to install, and how long-lasting the product was. They also promoted metal ceilings as being safer than their wood and plaster counterparts, being fireproof, dust-free, and “vermin proof”. Yikes!

-

“Steeling” the Spotlight

Contrary to popular belief, ornamental metal ceilings in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were made of steel for durability and strength, as tin isn’t strong enough on its own for such a task. Some makers of steel ceiling panels eventually tin plated or galvanized (coated with zinc) their products to prevent corrosion, but at the turn of the century it was cheaper to paint them with primer to achieve a similar effect. Why, then, are they called tin ceilings? Who knows! Maybe because of the eventual tin coating, or maybe because metal workers were often called “tin smiths”. All of the period trade catalogs we looked at , however (and there were many!), called them steel ceilings, not tin. (Note – The paint used to prime the steel panels were usually lead-based, which definitely knocks their “safety” rating in our books!)

Contrary to popular belief, ornamental metal ceilings in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were made of steel for durability and strength, as tin isn’t strong enough on its own for such a task. Some makers of steel ceiling panels eventually tin plated or galvanized (coated with zinc) their products to prevent corrosion, but at the turn of the century it was cheaper to paint them with primer to achieve a similar effect. Why, then, are they called tin ceilings? Who knows! Maybe because of the eventual tin coating, or maybe because metal workers were often called “tin smiths”. All of the period trade catalogs we looked at , however (and there were many!), called them steel ceilings, not tin. (Note – The paint used to prime the steel panels were usually lead-based, which definitely knocks their “safety” rating in our books!)

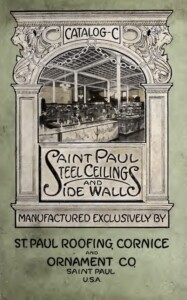

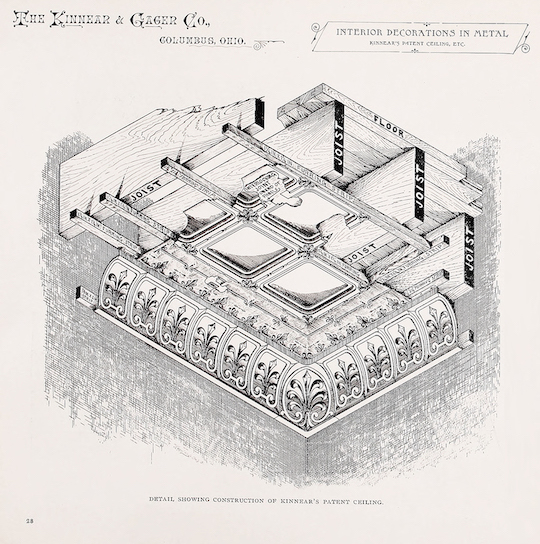

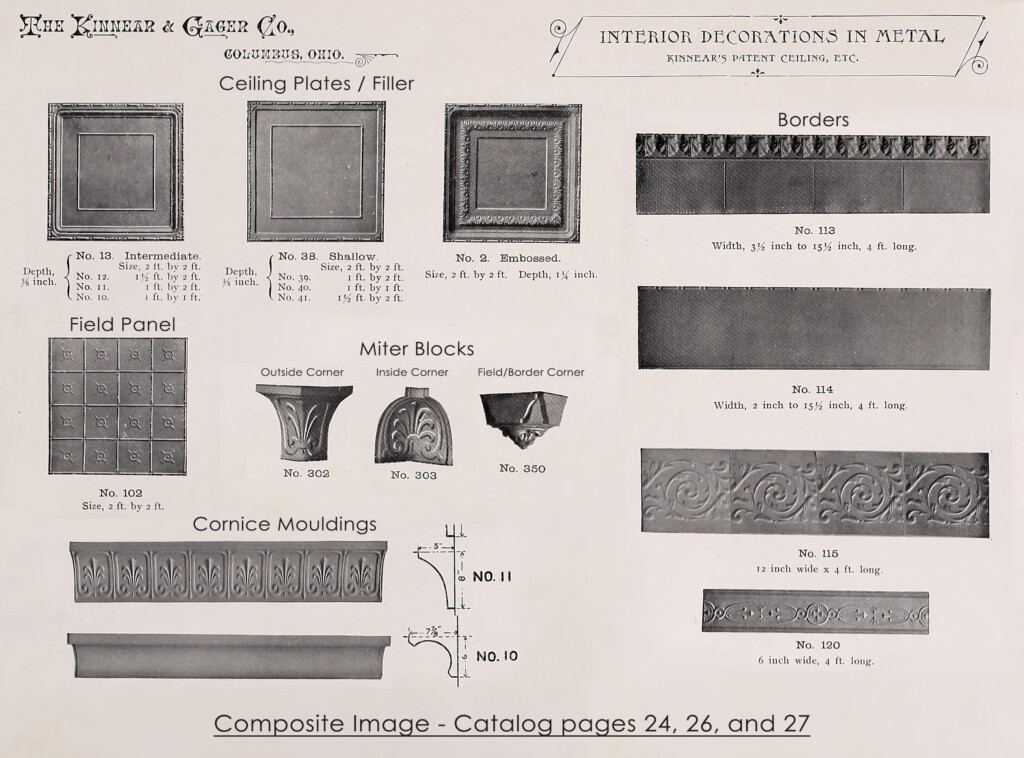

The first decorative metal ceilings were made of corrugated steel, with separate moldings attached to it for ornamentation. It wasn’t until 1888 that the W. E. Kinnear Company of Columbus, OH, created ceiling panels with the decoration stamped or pressed into them, like those we have at Rosson House. Coincidentally enough, that same company (Kinnear & Gager Co.) made the Rosson House metal ceiling panels (make sure read through to the very bottom of the page for images and more information about our ceilings).  Makers of ornamental metal ceilings enjoyed the same boom in sales that other businesses did through mail-order catalogs at the turn of the century, and many buildings at that time had metal ceilings installed. With just a quick browse through period Arizona newspapers, we found reference to metal ceilings being installed in homes, schools, jails, mercantiles, theaters, and offices all over the Territory (and the country), including in the assembly room of the Tempe “Normal School” (ASU) in 1898, the Grand Canyon Hotel in Williams in 1901, and the Santa Cruz County Courthouse in Nogales in 1903. People who were building new homes or updating their current ones could order a decorative metal ceiling, along with the furring strips and nails to put it up, and the paint to finish it (yes, they were meant to be painted!). The catalogs described how to measure for an ornamental metal ceiling, and sometimes even had a drawing that showed what the process of installation would look like, like the one you see on this page from the 1890 Kinnear & Gager Co. catalog. When ordering a ceiling, there were many businesses to choose from – even Sears, Roebuck and Co. had a catalog selling decorative metal ceilings – and even more styles and patterns. Your ceiling of choice could be Colonial, Empire, French Renaissance, Gothic, Greek, Louis XIV, Rococo, Romanesque, and more, and then there were different designs to choose from under each of those styles, from simple to more ornate. They could even add ornamental metal wall panels to their design.

Makers of ornamental metal ceilings enjoyed the same boom in sales that other businesses did through mail-order catalogs at the turn of the century, and many buildings at that time had metal ceilings installed. With just a quick browse through period Arizona newspapers, we found reference to metal ceilings being installed in homes, schools, jails, mercantiles, theaters, and offices all over the Territory (and the country), including in the assembly room of the Tempe “Normal School” (ASU) in 1898, the Grand Canyon Hotel in Williams in 1901, and the Santa Cruz County Courthouse in Nogales in 1903. People who were building new homes or updating their current ones could order a decorative metal ceiling, along with the furring strips and nails to put it up, and the paint to finish it (yes, they were meant to be painted!). The catalogs described how to measure for an ornamental metal ceiling, and sometimes even had a drawing that showed what the process of installation would look like, like the one you see on this page from the 1890 Kinnear & Gager Co. catalog. When ordering a ceiling, there were many businesses to choose from – even Sears, Roebuck and Co. had a catalog selling decorative metal ceilings – and even more styles and patterns. Your ceiling of choice could be Colonial, Empire, French Renaissance, Gothic, Greek, Louis XIV, Rococo, Romanesque, and more, and then there were different designs to choose from under each of those styles, from simple to more ornate. They could even add ornamental metal wall panels to their design.

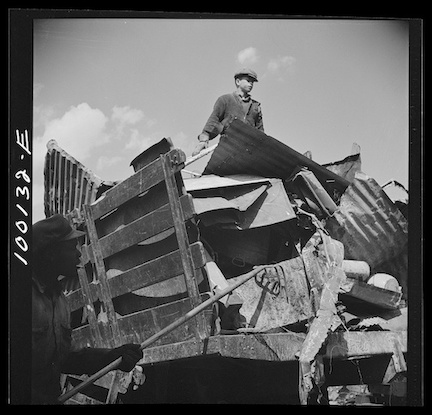

A boy standing on a pile of scrap metal during a World War II scrap metal drive. Do we see decorative metal ceiling tiles directly under him?

Catalogs specifically dedicated to selling decorative metal ceilings were around into the late 1930s, but they were less popular than they had been. The trend of ornate fixtures and furnishings went out of style after the first World War and the Great Depression. But the nail in the coffin for metal ceilings was World War II, when all steel production went towards making war materials and unused or unwanted metals were recycled for the same. After the war, the architectural style of the mid-century modern meant less was more, and Victorian Era homes were stripped of their original, ornate decorative finishes, including their metal ceilings. We are lucky that the majority of the metal ceilings at Rosson House survived, though in most rooms they were hidden by drop ceilings that covered additional plumbing and electrical installed while it served as a boarding house.

During restoration of the home, workers tore out the additions and found the original ceilings in bad shape:

“The pressed tin ceilings were badly chipped and had multiple layers of paint on the panels creating an “alligator” appearance. Several samples of paint were removed from the panels (the flat and raised areas) and looked at microscopically. The chips were sent to a paint laboratory in California for chemical analysis as to content and sheen of the bottom layer. Each room had a first layer of a soft green primer paint followed by an application of lead-based paint in a medium sheen. Next, the paint chips were sent to an expert with the National Parks Service in Denver who color-coded them with the Munsell System for coding historical paint colors. The paints were then reproduced locally; however, the lead content was eliminated.

The family parlor at Rosson House, prior to restoration.

The method of preparing the old ceilings for the new paint was controversial. The debate concerned whether or not to remove the old paint first. It was finally concluded to lightly sandblast the ceilings, leaving one pane in each room intact for future reference.

At some point during the remodeling of the house, a second staircase was added to the attic at the point where the front hall staircase comes to a landing on the second floor. Those ceiling panels were apparently discarded where the hole had been cut to accommodate the new staircase. Because the panels in the northeast room on the first floor (the doctor’s office) matched the missing panels, they were removed and used to fill in upstairs. That room (the doctor’s office) now has a new ceiling created from old (metal) panels of the era that were purchased in Ohio.”

– Rosson House Restoration Notes, Mary Hudak, August 1988

Additional Info – Since you’ve gotten this far, we thought we’d give you a little more info about the Rosson House ceilings. When you look at some of the pictures or go on a tour, sometimes you’ll see a metal disk in the ceiling, sometimes painted and sometimes not, and you’ll think, “What is that??” The answer is that those disks cover the sprinklers for the fire suppression system at Rosson House. If there’s a fire (knock on wood and fingers and toes crossed it never happens!), those disks pop off the sprinklers at 135°. When they’re painted, they lose seconds of effectiveness – with one coat they are slower by 4 seconds, with two coats they’re slower by 9 seconds. So, some were left unpainted in order to make them as effective as possible. Now you know!

Information for this article was found in the Heritage Square archives; in period trade catalogs from the amazingly extensive digital Building Technology Heritage Library, available through the Internet Archive; in period newspapers from the Library of Congress Chronicling America digital archive; from the National Park Service papers on Preserving Historic Ornamental Plaster and Historic Decorative Ceilings and Walls: Use, Repair, and Replacement; and from the JSTOR article, Ornamental Sheet Metal in the United States, 1870-1930.

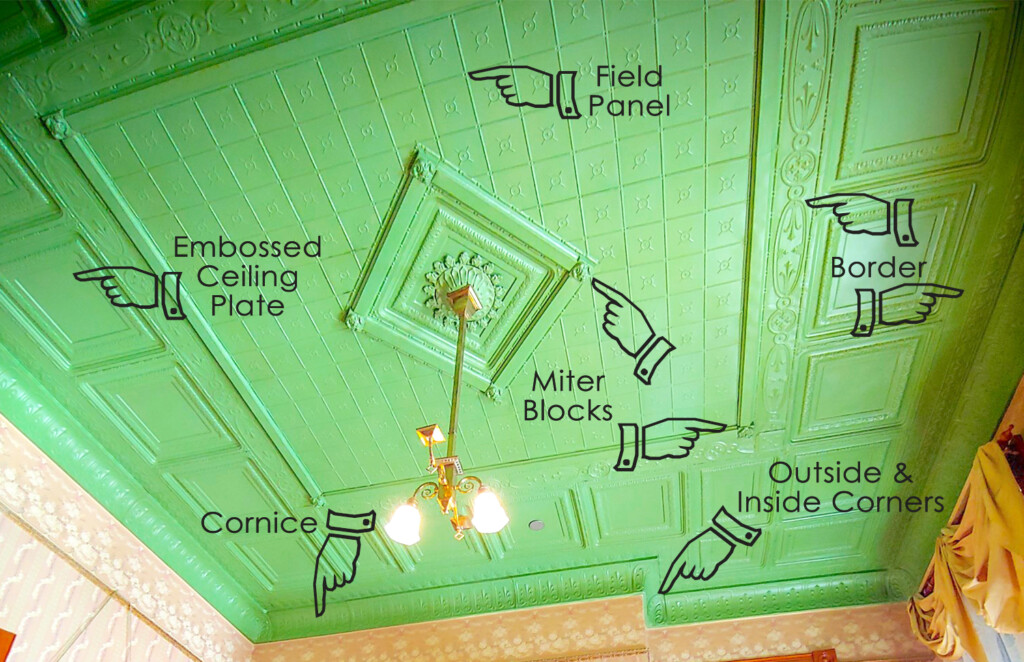

We found many of Rosson House’s original, ornamental metal ceiling elements in the 1890 Kinnear & Gager Co. catalog. Below is a composite image from the catalog that shows many of the ceiling pieces you’ll find at the home, along with an image of our dining room ceiling, pointing out many of those same pieces. We believe the doctor’s office ceiling was originally purchased from the Wolf Steel Ceiling Co. (as shown in their 1910 catalog, page 4).

More Ceilings at Rosson House

The Family Parlor

The Doctor’s Office

The Nursery

Archive

-

2024

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-