Science & Science Fiction

For a printable version of this article, please click here.

Did you know…

Even before it was physically possible to do so, people were exploring our world and the universe beyond with just their imagination. This curiosity led to centuries of stories speculating about life here on Earth, in the oceans, on distant lands, or even at its center, and on the Sun, Moon, stars, and various planets. Some stories predate modern scientific thought, like A True Story – a satire about lunar travel written over 2,000 years ago by Lucian of Samosata. But many stories were both inspiration for and were inspired by scientific exploration and discovery, and technological advancement.

Even before it was physically possible to do so, people were exploring our world and the universe beyond with just their imagination. This curiosity led to centuries of stories speculating about life here on Earth, in the oceans, on distant lands, or even at its center, and on the Sun, Moon, stars, and various planets. Some stories predate modern scientific thought, like A True Story – a satire about lunar travel written over 2,000 years ago by Lucian of Samosata. But many stories were both inspiration for and were inspired by scientific exploration and discovery, and technological advancement.

From about the 16th century onward in Europe, there were several significant changes happening all at same time – the Age of Discovery (15th-17th centuries), a time of world exploration with changes in travel, trade routes, and knowledge of the world; the Scientific Revolution (1543-1687), a change in scientific thought led by new discoveries in mathematics, physics, astronomy, chemistry, and biology; the Age of Enlightenment (17th and 18th centuries), a time of changes in political, philosophical, and scientific thought; and the first Industrial Revolution (1760-1840), a time when people changed from an agrarian society that created goods by hand, to one that relied on technology and mechanization to manufacture goods. As people had information available to them at a level they hadn’t had before, anything was possible, good or bad. Speculative writing – whether meant to be fiction or nonfiction – helped bridge the gap between what had been and was being discovered, and what was still unknown.

-

More Info: What is Science Fiction?

Photo by Maxime Raynal, 2016.

Science fiction as a term was popularized in the 1920s about creative, speculative storytelling based on how science and technology affect individuals and society as a whole. Many works of science fiction are created as satire – a method of storytelling that exposes flaws in a powerful person or system by emphasizing or exaggerating those flaws – or as a warning of what could happen in the future.

Today, science fiction storytelling is generally characterized by five elements:

-

- A “What if?” question (e.g. – what if there were creatures at the center of the Earth, or what if beings from another planet visited Earth on April 5, 2063?)

- An unfamiliar setting (e.g. – a dystopian, apocalyptic Earth, or a space station in another solar system)

- Innovative technology (e.g. – the ability to reanimate the dead, or the ability to change a person’s DNA with a bite from a genetically altered spider)

- Relatable characters (e.g. – cute little robots that help blow up moon-sized space stations, or other cute little robots that help humans find their way back to Earth).

- Themes about humanity (e.g. – what it means to be human, with all the struggles, joys, and complications of life)

-

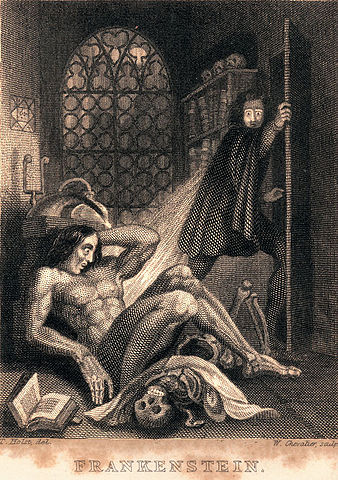

Biological exploration in the 17th century led to discoveries of things like red blood cells and microorganisms in the search for what made life possible, but they didn’t stop with the small stuff. Doctors and scientists also built anatomical theaters specifically to showcase the dissection and exploration of the bodies of animals and humans, eagerly watched by scientists, medical students and even the general public. (Side Note – One of the first anatomical theaters built in the US was designed by Thomas Jefferson for the University of Virginia). Many cadavers used for this purpose were stolen from graveyards by “resurrectionists” and sold to medical schools for dissection and experimentation.

Biological exploration in the 17th century led to discoveries of things like red blood cells and microorganisms in the search for what made life possible, but they didn’t stop with the small stuff. Doctors and scientists also built anatomical theaters specifically to showcase the dissection and exploration of the bodies of animals and humans, eagerly watched by scientists, medical students and even the general public. (Side Note – One of the first anatomical theaters built in the US was designed by Thomas Jefferson for the University of Virginia). Many cadavers used for this purpose were stolen from graveyards by “resurrectionists” and sold to medical schools for dissection and experimentation.

The experiments of Luigi Galvani and Giovanni Aldini in the late 18th and early 19th centuries included electrifying bodies or body parts to make their muscles twitch, leading to questions about whether reanimation of life was possible. It was at this time that Mary Shelley wrote what’s generally considered to be the first true science fiction novel, believed to be so because her “monster” was created solely by a scientist rather than through some magical force or because of some mythical creature. Her book pit nature against science and technology, combined with hubris and ambition. Robert Louis Stevenson’s book, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), about a doctor who discovers a way to separate his good side from his bad side, has a similar theme. Neither book has a happy ending for the person who dabbled in “dangerous” scientific experimentation.

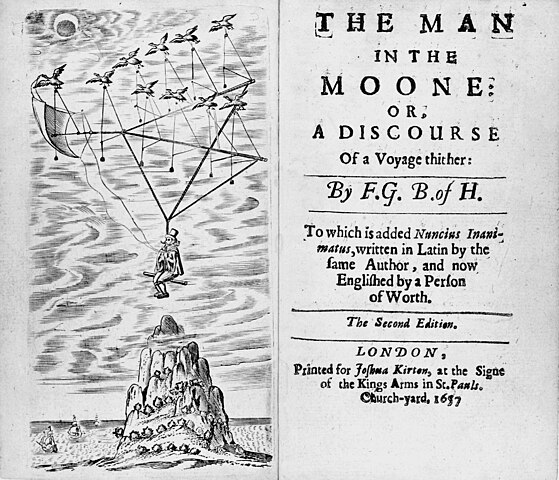

Though space exploration had been imagined for hundreds of years prior, Galileo’s telescopic observations of the Moon and its topography in 1609 led many to believe it, as well as other planets and even the sun, sustained life. People write both fictional accounts and nonfictional speculation about what life on the Moon could look like. In 1638, John Wilikins, an English bishop, wrote The Discovery of a World in the Moone, saying “tis probable there may be inhabitants in this other World,” and another bishop, Francis Godwin, wrote a fictional account of a Spanish nobleman’s voyage to the Moon in The Man in the Moone. Though Godwin’s story was fictional, his portrayal of space as weightless – a first for anyone – was correct. Other people writing about space exploration and extraterrestrials at this time included:

-

- Johannes Kepler, who developed the laws of planetary motion (1609-1618) and also wrote Somnium(1609), a fictional account of a boy who travels to the Moon.

- Margaret Cavendish, the Duchess of Newcastle, who wrote The Blazing World (1666) about a woman who travels to another world through the North Pole and talks with the varied and diverse creatures who live there.

- Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle, a highly regarded French writer and longtime member of the Adadémie des Sciences, who wrote Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds (1686), a set of fictional conversations between a philosopher and his hostess who look at the night sky and consider the possibility of extraterrestrial life.

- Voltaire, a French writer and philosopher during the Enlightenment who advocated for freedom of expression and separation of church and state, and who also wrote a short story called Micromégas (1752) about two visitors to Earth – one from a planet that orbits the star Sirius, and the other from Saturn.

- Jules Verne, sometimes considered to be the father of modern science fiction, who wrote From the Earth to the Moon (1865) and its sequel, Round the Moon (1869), about a group of Civil War veterans who use “new technology” (i.e. – a cannon) to travel to the Moon.

-

More Info: Hair-Raising Hoaxes

A couple of stories told a century apart fooled people into believing in extraterrestrial life – one story told about life on the Moon, and the other about life from Mars. Neither were initially meant to be a hoax, but both ended up being very misleading, at least for a time.

A couple of stories told a century apart fooled people into believing in extraterrestrial life – one story told about life on the Moon, and the other about life from Mars. Neither were initially meant to be a hoax, but both ended up being very misleading, at least for a time.The Great Moon Hoax

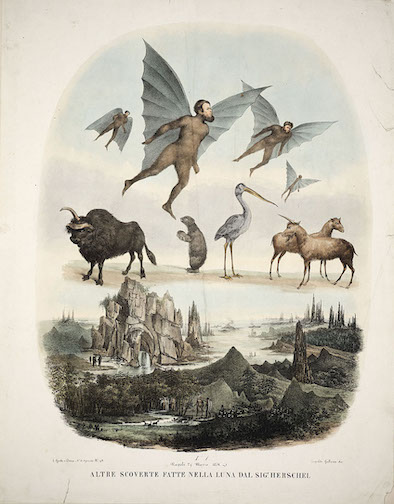

This story began as a series of articles published by the New York Sun in 1835, supposedly written by a Dr. Andrew Grant who reported on astronomer’s recent observations of amazing creatures on the Moon, including unicorn bison, horned bears, and bat-people (see lithograph). People were fascinated by the descriptions of the Moon, its topography, and its inhabitants. Though the author of the articles turned out to be Richard Adams Locke, a reporter for the newspaper who had written the articles as satire, the story had a life of its own. It was reprinted across the US and in Europe, plays were staged and songs were written about the life discovered there, and in Italy, beautiful lithographs of the creatures were made according to the articles’ descriptions.Interesting Side Note – The existence of The Great Moon Hoax coincidentally exposed a different story that was actually intended to be a hoax. The story – The Unparalleled Adventures of One Hans Pfaal – which was also written in 1835, was about a man who traveled to the Moon in a balloon, and the author never forgave Locke for having interfered with his attempt at fooling the public. The author’s name? Edgar Allan Poe.

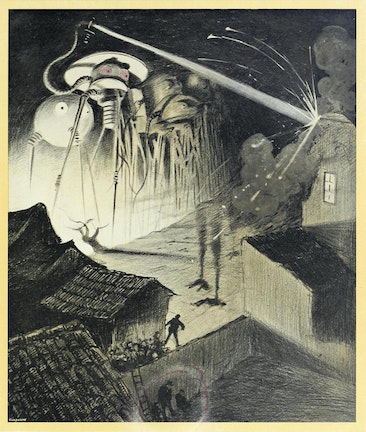

War of the Worlds illustration by Brazilian artist Henrique Alvim Corrêa, 1906.

The War of the Worlds

Written by HG Wells in 1897, The War of the Worlds tells of Martians that invade England in an attempt to take over our world because their own is dying. The book was successful, but the story really went “viral” (so to speak) when it was transmitted as a radio program in the US on Halloween Eve in 1938. Many people who turned on their radio sets after their Sunday dinner were horrified to hear that Martians had crashed into a field in New Jersey and fired a heat ray that killed 7,000 members of the National Guard. As the radio broadcast told of more Martians landing all over the country, people called in to radio stations, police stations, fire departments, newspapers, and anyone else that might know what was happening and what to do about it. The answer, however, was that nothing was happening. There were no Martians or heat rays, and the National Guard was just fine. What they had heard was a fictional radio program created by Orson Wells, and based on the HG Wells book. There is some question as to how many people truly believed the story was real, but the panic made the news out here in Arizona, and a local newspaper reported people calling in to learn details about the “catastrophe in the East.”Was the program that good? You be the judge! You can listen to the entire War of the Worlds radio broadcast from the Internet Archive.

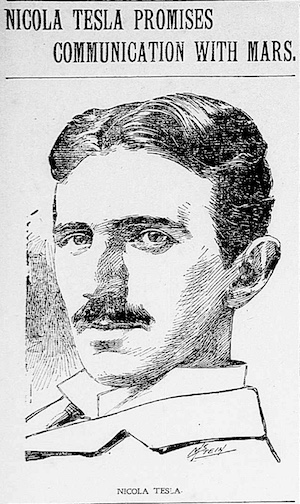

More discoveries, like Giovanni Schiaparelli’s 1877 identification of canali on Mars (meaning channels, but mistranslated as canals) further fueled the speculative fire about space exploration and life on other planets, both in fiction and nonfiction. Mathematician and astronomer Percival Lowell built his observatory in Flagstaff, AZ in 1894 specifically to observe Mars and detect life there, based on Schiaparelli’s observations. He contributed articles for Scientific American, Century Magazine, and The Atlantic, and gave lectures all over the US, and oversees to the Royal Institute of London and the Association Astronomique in Paris. Lowell followed that up with three books based on his observations – Mars (1895), Mars and its Canals (1906), and Mars as the Abode of Life (1909). Many people believed Lowell’s account, including scientist and inventor, Nicola Tesla, who thought that communication with Mars might be possible. Science was bolstered by literature with books like HG Wells’ War of the Worlds (1898), serials like Edison’s Conquest of Mars (1898), and plays like A Message from Mars (1899). Other fiction writers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries described life on Mars as having evolved similarly to life on Earth with humanoid life forms that had blue, red, and green skin. Luckily, they did speak English.

More discoveries, like Giovanni Schiaparelli’s 1877 identification of canali on Mars (meaning channels, but mistranslated as canals) further fueled the speculative fire about space exploration and life on other planets, both in fiction and nonfiction. Mathematician and astronomer Percival Lowell built his observatory in Flagstaff, AZ in 1894 specifically to observe Mars and detect life there, based on Schiaparelli’s observations. He contributed articles for Scientific American, Century Magazine, and The Atlantic, and gave lectures all over the US, and oversees to the Royal Institute of London and the Association Astronomique in Paris. Lowell followed that up with three books based on his observations – Mars (1895), Mars and its Canals (1906), and Mars as the Abode of Life (1909). Many people believed Lowell’s account, including scientist and inventor, Nicola Tesla, who thought that communication with Mars might be possible. Science was bolstered by literature with books like HG Wells’ War of the Worlds (1898), serials like Edison’s Conquest of Mars (1898), and plays like A Message from Mars (1899). Other fiction writers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries described life on Mars as having evolved similarly to life on Earth with humanoid life forms that had blue, red, and green skin. Luckily, they did speak English.

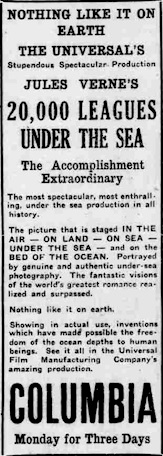

The beginning of the 20th century saw other avenues for science fiction writing. Though some sci-fi stories, like 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, had originally been serialized – that is, published as a series of installments in newspapers or magazines rather than as bound books – the 1920s and 1930s saw a boost in science fiction writing with the publication of magazines completely dedicated to the genre. Pulp magazines like Amazing Stories were published monthly with a handful of short stories or serialized longer ones, and bright, stylized cover art. The Amazing Stories first edition in 1926 included works by Jules Verne, HG Wells, Edgar Allan Poe, and more. Those writers would also influence a new creative outlet with science fiction films, and many silent films were based on their popular stories – “A Trip to the Moon” (1902) by George Méliès was influenced by Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon, “Frankenstein” was first produced by Thomas Edison’s movie studio in 1910, “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea” was made in 1916, and “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” in 1920.

Arizona Republican newspaper ad, May 3, 1917.

Though we know many things about the people who lived at Rosson House and at Heritage Square as a whole, unfortunately we don’t know what kinds of books or magazines they read, or what films they watched. Local newspapers from the late 19th and early 20th centuries mention Frankenstein (though not the character’s creator, Mary Shelley), along with popular authors Jules Verne, Robert Louis Stevenson, and HG Wells. Books were available to people in Arizona through subscription libraries, stores, and mail-order catalogs. Traveling companies showed films in the Territory starting in the late 19th century, and Phoenix and other Arizona towns would have permanent movie theaters by the early 1900s.

Join us over the next several months as we explore more about the past, present, and future of science fiction – it’s Sci-Fi Squared!

The main picture at the top of the page is an image of a production still from the 1902 film, “A Trip to the Moon”.

Learn more about the history of books and libraries in Arizona from our blog article, By the Book, and about the history of films from our blog article, Moving Pictures.

Explore the Smithsonian Libraries’ exhibit, Fantastic Worlds: Science & Fiction 1780-1910.

Find archived copies of Amazing Stories on the University of Pennsylvania Libraries Online Books Page.

Information for this article was found online at the Library of Congress – Chronicling America Digital Newspaper Archive, and Finding our Place in the Cosmos-Life on Other Worlds: People & Creatures of the Moon, Seeing and Interpreting Martian Oceans and Canals, Envisioning Martian Civilizations ;The Collector – Lucian’s True Story, the First Sci-Fi Novel in History?; The Atlantic – The Science Fiction that Came Before Science; Wired – Was Voltaire the First Sci-Fi Author?; Smithsonian Magazine – The Enchanting Sea Monsters on Medieval Maps, and In Need of Cadavers, 19th Century Medical Students Raided Baltimore’s Graves; Linda Hall Library – Scientist of the Day: Giovanni Aldini; Santa Clara University Library – 200 Years of Frankenstein; The Conversation – Frankenstein, and Guide to the Classics: Mary Shelley’s The Last Man…; National Museum of Civil War Medicine – A Brief History of the Anatomy Riots; Encyclopedia Virginia – Anatomical Theater; NASA – The ‘Canali’ and the First Martians, and Galileo’s Observations of the Moon, Jupiter, Venus and the Sun; Folger Shakespeare Library Blog – ‘The Blazing World’ by Margaret Cavendish…; Lone Star College – Science Fiction Day; Smithsonian Magazine – The Great Moon Hoax Was Simply a Sign of its Time; Edgar Allan Poe National Historical Site – Edgar Allan Poe Pioneers Science Fiction; Unbound (Smithsonian Library Blog) – The Moon Hoax of 1835: Great Astronomical Discoveries; Great Moon Hoax Continues: Lunarian Discovered; The Great Moon Hoax or Was It: The Joke’s on Who?; Literary Hub – A Brief of Sci-Fi’s Love Affair with the Red Planet; the Lowell Observatory; TCM – A Trip to the Moon; Den of Geek – The 10 Best Silent Era Sci-Fi Films; The Public Domain Review – A 19th-Century Vision of the Year 2000; Britannica – Science Fiction, Scientific Revolution, and Industrial Revolution; The Pulp Magazines Project – Amazing Stories and Astounding Stories.

Archive

-

2024

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-