Hit the Road

Did you know…

Route 66 might be Arizona’s (and our nation’s) most famous road, but there were roads that crisscrossed both long before that bit of pavement hit the desert sand. We may think of mostly in how they relate to cars, but roads existed thousands of years before the motorized vehicle. In fact, the oldest known paved roads – mud brick in the Indus Valley and stone in Mesopotamia – date as far back as 4000 BCE. Mayans started building their sacbe, a series of roads, walkways, causeways, and dikes that connected communities throughout their empire, around 600 BCE. The Romans (all roads lead to Rome!) and Chinese also created vast paved road systems, beginning around 300 BCE, that connected trade routes for the latter, and military routes for the former.

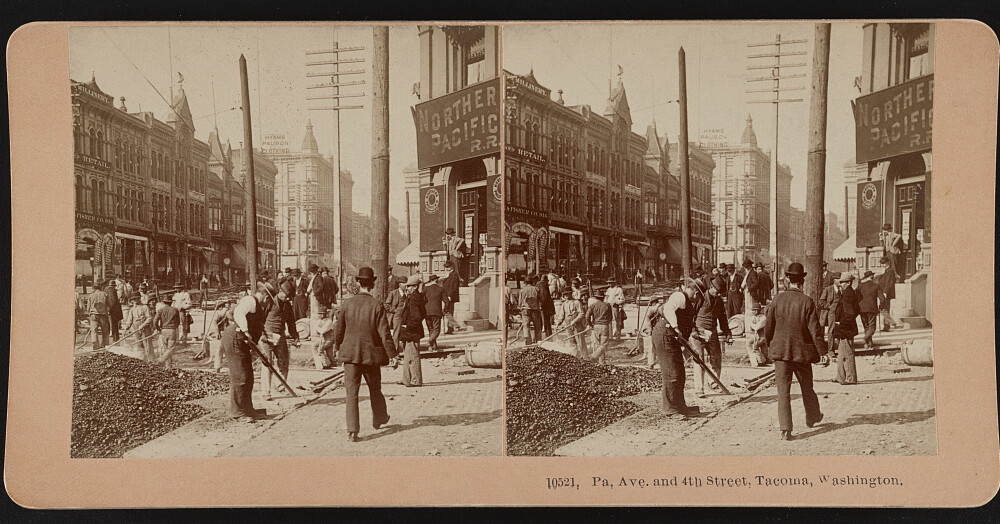

Many roads in America began as paths and trails originally established by Native Americans, and used for trade, hunting, and communication. The earliest European immigrants followed those paths, and would eventually make some into bigger roads that wagons and carriages could travel. Until the later part of the 19th century, road “pavement” would consist of materials like logs, wood blocks, bricks and stones to create a roadbed (for example, Pennsylvania Avenue, which runs in front of the White House, was paved with wood blocks after the Civil War). Asphalt and coal-tar roads – made when a road surface (usually stone or concrete) was sealed by tar, extending its life – began appearing in urban areas by the late 1800s.

-

Rocky Road

(great, now we want ice cream)

In the 19th century, roads for wagon trains migrating west were extremely poor. Martha Summerhayes, the wife of a US army officer stationed in Arizona, recorded her experience traveling over the new wagon trail built in the 1870s through the central Arizona mountains, saying:

“The roads had now become so difficult that our wagon-train could not move as fast as the lighter vehicles or the troops. Sometimes at a critical place in the road, where the ascent was not only dangerous, but doubtful, or there was, perhaps, a sharp turn, the ambulances waited to see the wagons safely over the pass . . . For miles and miles the so-called road was nothing but a clearing, and we were pitched and jerked from side of side of the ambulance, as we struck large rocks or tree- stumps; in some steep places, logs were chained to the rear of the ambulance, to keep it from pitching forward onto the backs of the mules. At such places, I got out and picked my way down the rocky declivity.”

With roads like these, it’s no wonder that stories of traveling in wagon trains are often filled with people walking the entire way! (though many walked to lighten the load, as wagons often were for supplies, not people) You can find out more about historic trails of Arizona, including the trail that Martha Summerhayes traveled, from the Arizona State Parks website.

-

Smooth Sailing

Like your smooth drive to work? Thank a bicyclist and your postal worker. Really!

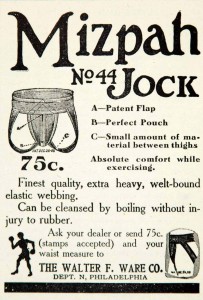

Like your smooth drive to work? Thank a bicyclist and your postal worker. Really!Victorian Era roads were beset with problems. When it rained, or during snow-melt, dirt roads could become impassable due to mud. The hot summer sun would permanently bake holes and deep ruts into place. To combat these problems, materials like logs and stones were used to “pave” roads, making them more solid, but still extremely bumpy. Driving over cobblestones was so jarring for early bicyclists that the jock strap (a term that referenced bicyclists as “jockeys”) was invented to protect male bicycle riders. That wasn’t enough for bicyclists, though, who wanted roads to be more bike-friendly, aka – smoother. They created the League of American Wheelmen, and lobbied the government for better roads. Congress would eventually create the Office of Road Inquiry (the forerunner of the Federal Highway Administration) in 1893. Three years later the US Postal Service further incentivized support for better roads by offering free mail delivery in rural areas (it was already available in cities), but only if the roads were deemed passable.

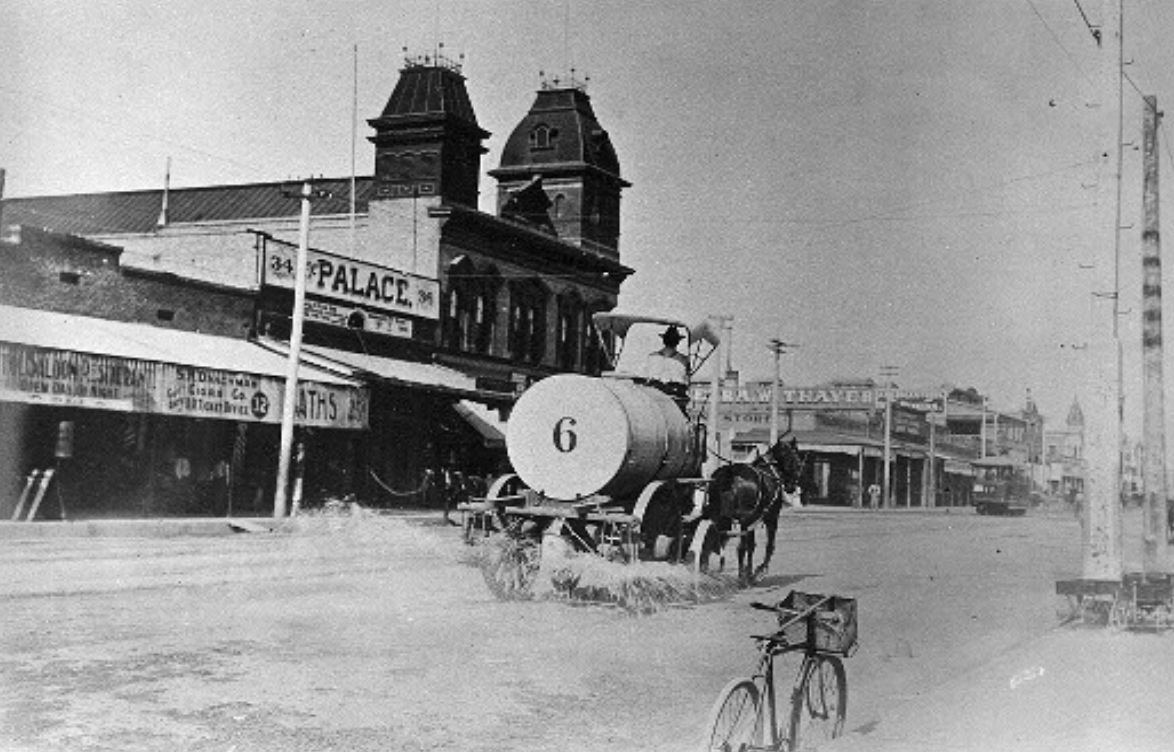

In Territorial Arizona, the first main roads were built by the US military in order to move people through the area – first for troops during the Mexican-American War, and then for prospective miners for the California Gold Rush. As the population grew and the Territorial Legislature was formed, responsibility for road building rested on individual municipalities and counties. Phoenix mandated street and sidewalk grading in 1886, and gutters in 1887. City streets at the time were unpaved dirt roads, and many had small ditches that ran along either side to carry water runoff and other, more unsavory things as well (see the picture of Rosson House, c1900, on the very right-hand side and in line with the front gate you can see a little wooden bridge that covers the ditch there). As early as the late 1870s, city streets were sprinkled with water to cut down on dust (something that still feels familiar today). In 1893, an accusation was made during a city council meeting that street sprinklers were being paid under the table to favor some streets, thereby neglecting others.

In Territorial Arizona, the first main roads were built by the US military in order to move people through the area – first for troops during the Mexican-American War, and then for prospective miners for the California Gold Rush. As the population grew and the Territorial Legislature was formed, responsibility for road building rested on individual municipalities and counties. Phoenix mandated street and sidewalk grading in 1886, and gutters in 1887. City streets at the time were unpaved dirt roads, and many had small ditches that ran along either side to carry water runoff and other, more unsavory things as well (see the picture of Rosson House, c1900, on the very right-hand side and in line with the front gate you can see a little wooden bridge that covers the ditch there). As early as the late 1870s, city streets were sprinkled with water to cut down on dust (something that still feels familiar today). In 1893, an accusation was made during a city council meeting that street sprinklers were being paid under the table to favor some streets, thereby neglecting others.

Wealth definitely had an effect on how a neighborhood’s streets were treated – early Phoenicians didn’t want to be taxed to pay for citywide infrastructure, but would advocate and even pay for their stretch of street to be graded and graveled. When Phoenix in 1911 specified what materials could be used to pave city streets, owners within the central business district together paid over $100,000 to have the Barber Asphalt Paving Co. (est. 1883) pave their streets. Wanting more streets to be paved, Phoenix would ask the Legislature to pass a measure that forced property owners to foot the bill, putting liens on owners’ property until they were paid. Though their focus seemed to be on paving all city streets, poorer neighborhoods, which were principally made up of Latinx and African American communities, were overlooked, with streets remaining unpaved well into the second half of the 20th century. Some of those neighborhoods no longer exist, as the people were forced out, and buildings were torn down and paved over when the interstate came through Phoenix (the same happening to minority communities throughout the United States).

Phoenix street sprinkler, c1900, Arizona Science Center

During the Depression, New Deal governmental programs funded infrastructure nationwide through the Works Progress Administration, the Civilian Conservation Corps, and the Public Works Administration (just three of many). These new departments would go on to complete enormous projects like the construction of the Lincoln Tunnel, which connected Manhattan to New Jersey; the Overseas Highway, which connected Florida to Key West; and (closer to home) the Salt River Project and the Hoover Dam. But there were multitudes of smaller projects that were completed, including hundreds of thousands of dollars invested employing Arizonans to improve and pave roads, bridges, and sidewalks here in their own communities.

As time goes on, so do road infrastructure projects. Last year, the City of Phoenix started a pilot program to coat streets with a light grey sealant in several neighborhoods. It’s a material that protects the street surface, but also reflects light from the sun instead of absorbing it like the darker asphalt does, reducing the urban heat island effect. The initial application of this new material produced a 15° cooler street surface, and we’re excited to see the results of this project when they’re released. Other new technology is changing the roads we drive on as well, as people are now using recycled plastics to build new roads, making roads that glow in the dark, and creating “smart roads” with sensors that can alert drivers to traffic jams and immediately alert the authorities when a crash occurs. (Fingers crossed that flying cars are next up on that transportation technology list!)

WPA road project, c1940; National Archives

Information for this article was found in the Phoenix Streetscape Conservation Report (2010); Good Roads Everywhere: A History of Road Building in Arizona (May 2003); Library of Congress Research Guides and Chronicling America Newspaper Archive; AZ Central; the US DOT Federal Highway Administration; Smithsonian Magazine (on bicyclists, and on infrastructure); ThoughtCo; Britannica; Asphalt Magazine; and the Living New Deal.

Archive

-

2024

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-