Victorian Cures & Quacks

Did you Know…

Bottles from the Heritage Square collection, including a blue Bromo Seltzer bottle found during restoration, c.1915.

There are a handful of things people who take a Rosson House tour invariably remember – the entryway staircase, the vertical pocket doors, the kitchen/pantry, and the doctor’s office (pictured above). Some may remember that last one with a little discomfort, what with all the interesting tools of the trade on display. Our docents and interpreters often have fun seeing people’s reactions when they describe the exact function of some of those tools, and also when they tell people about Dr. Rosson’s medical background. For those of you who don’t know, or have forgotten, Dr. Rosson received a medical degree from the University of Virginia in 1873 after having taken four classes. You read that right – four! They were: anatomy, chemistry, medicine, and pharmacology/surgery. Not many medical practitioners actually held medical degrees at that time, and concocting medicines was not restricted to pharmacists. That made the medicines themselves anything from benign, addictive, or even poisonous. And it also made them pretty big business for anyone who happened to be interested in selling.

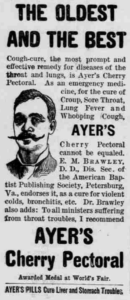

Individuals like Isaac Edward Emerson and James Cook Ayer both had some training – Emerson had a chemistry degree and Ayer had a medical degree – and yet both concocted medicines that wouldn’t pass today’s safety standards. Ayer’s Cherry Pectoral (ad pictured to the right) was meant to cure anything from a simple cold or cough, up to lung diseases, including tuberculosis. Pectoral ingredients were said to be herbs, but also included alcohol and three grams of morphine per bottle, which might cure anyone’s urge to cough, or even breathe! Emerson’s Bromo Seltzer was very popular as a headache remedy, but the active ingredient – acetanilide – could cause liver and kidney damage. Many doctors at the time would prescribe Fowler’s Solution (a curative for syphilis invented in the late 1700s), despite the fact that it included both mercury and arsenic.

Individuals like Isaac Edward Emerson and James Cook Ayer both had some training – Emerson had a chemistry degree and Ayer had a medical degree – and yet both concocted medicines that wouldn’t pass today’s safety standards. Ayer’s Cherry Pectoral (ad pictured to the right) was meant to cure anything from a simple cold or cough, up to lung diseases, including tuberculosis. Pectoral ingredients were said to be herbs, but also included alcohol and three grams of morphine per bottle, which might cure anyone’s urge to cough, or even breathe! Emerson’s Bromo Seltzer was very popular as a headache remedy, but the active ingredient – acetanilide – could cause liver and kidney damage. Many doctors at the time would prescribe Fowler’s Solution (a curative for syphilis invented in the late 1700s), despite the fact that it included both mercury and arsenic.

Women got in on the medicine act as well, using their status as caretakers, mothers, and grandmothers to sell remedies of all sorts. Lydia Pinkham bottled up homemade, “Vegetable Compound,” that supposedly cured “female weakness” (code for unnamed menstrual and menopausal issues), as well as general headaches, nervousness, and irritability. Her remedy was twenty percent alcohol, which could definitely contribute to taking a nap after a dose, if not actual curing of the symptoms listed. Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup, a cure for painful teething in infants and children, used the idea of a wonderful, caring mother to sell the medicine. However, the actual Mrs. Winslow had passed away by the time her son-in-law was inspired to create the medicine, a dose of which would include both morphine and alcohol.

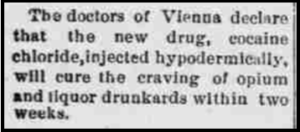

Newspaper clip from the February 7, 1885 Arizona Sentinel

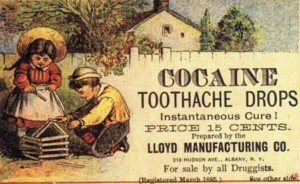

Many of these patent medicines included morphine and alcohol, but also could contain heroin or cocaine, as in the Cocaine Tooth Drops made by the Lloyd Manufacturing Co. Note these, like Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup, are obviously meant for consumption by children. Cocaine was also billed as a curative for opium addiction. Alcohol was supposedly just used as a preservative in these medicines, but most, like Lydia Pinkham’s, contained around fifteen to twenty percent. Parker’s Tonic (advertised to cure coughs, consumption, asthma, blood diseases, rheumatism, nervousness, and liver and kidney complaints) was supposedly made entirely from pure vegetable extracts, but was actually 41.6% alcohol. It’s no wonder these elixirs were so popular during Prohibition!

Many of these patent medicines included morphine and alcohol, but also could contain heroin or cocaine, as in the Cocaine Tooth Drops made by the Lloyd Manufacturing Co. Note these, like Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup, are obviously meant for consumption by children. Cocaine was also billed as a curative for opium addiction. Alcohol was supposedly just used as a preservative in these medicines, but most, like Lydia Pinkham’s, contained around fifteen to twenty percent. Parker’s Tonic (advertised to cure coughs, consumption, asthma, blood diseases, rheumatism, nervousness, and liver and kidney complaints) was supposedly made entirely from pure vegetable extracts, but was actually 41.6% alcohol. It’s no wonder these elixirs were so popular during Prohibition!

Thankfully, the initial Pure Food & Drug Act of 1906 was enacted to help solve the problem of unregulated medicines, to be replaced by the more stringent Federal Food, Drug, & Cosmetic Act of 1938.

Information for this article was found online at the Hagley Museum & Library, the Pilgrim Museum, the New England Historical Society, The Embryo Project Encyclopedia, and Culinary Lore.

Archive

-

2024

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-