Museum Miscellany

For a printable version of this article, please click here.

Did you know…

A Museum Collection is a group of artifacts (including archives) and/or scientific specimens

that are relevant to an organization’s mission, mandates, history, and themes,

and which the organization manages, preserves, and makes available for access

(through research, exhibits, and other media) for the public benefit.

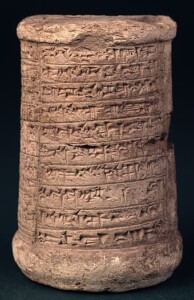

A clay cylinder used in Ennigaldi-Nanna’s museum to label an even more ancient artifact.

Last fall we received a generous grant from the Arizona Historical Society to upgrade our collections software to a cloud-based platform. With this came the opportunity to give into curiosity and do a deep dive into the new database to see what’s there, and to share that with you! First, though, a little history…

While conducting an archaeological dig at an ancient Babylonian palace in 1925, archaeologists found a collection of items dating from 2100 BCE to 600 BCE, grouped together and labeled on clay cylinders in three different languages. The collection is thought to have been arranged by priestess Ennigaldi-Nanna, the daughter of the Neo-Babylonian king, Nabonidus, and is considered to be the world’s first museum. The first museum in America – the Charleston Museum of Charleston, South Carolina – was established in 1773, pre-dating our nation’s independence by just a few years. Their initial collection was more like that of a natural history or science museum, and included “all the natural productions, either animal, vegetable or mineral…with accounts of the various soils, rivers, waters, springs, & c., and the most remarkable appearances of the different parts of the country.”

-

Problematic Pieces

A bronze sculpture of the Benin Kingdom, 16th-18th century, Nigeria. Currently in the collection of the Louvre Museum.

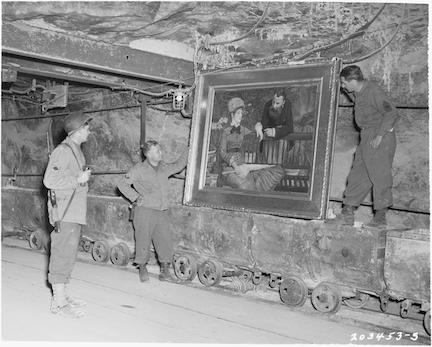

Throughout history, many museums were established with objects that were indiscriminately “collected” with no regard to who the pieces actually belonged to, or whether it was ethical to take them in the first place. These objects included priceless cultural antiquities, including the Benin Bronzes from what is now Nigeria, the Elgin Marbles from Greece, and ornate statues and carvings from temples in Cambodia, Thailand, India, Burma, etc. Whether or not putting stolen artifacts on display was the wrong thing to do in the past, museums are now reckoning with this dodgy history. In 2020, the San Francisco Asian Art Museum was sued by the US Justice Department to facilitate the return of looted artifacts from Thailand. The Metropolitan Museum of Art returned two Benin Bronzes to Nigeria in 2021 – just a fraction of the 160 artifacts the museum holds from Benin City, which was looted by British troops in the 1890s. Thirteen artifacts identified as being stolen were returned by the Yale University Art Gallery in 2022. And museums aren’t the only ones having to return plundered artifacts. During World War II, the Nazis looted hundreds of thousands of pieces of art from all over Europe, many of them from Jewish people who later died in the Holocaust. Both during and since the war, individual collectors, museums, and governments have had to return stolen art and artifacts to their original owners or their descendants, a process that remains ongoing today. Hobby Lobby smuggled 5,500 artifacts out of Iraq in 2010 against federal law. They were forced to return the artifacts, paying a $3 million fine. In 2021, hedge fund billionaire Michael H. Steinhardt returned 180 stolen artifacts worth over $70 million as part of a plea deal, and was banned from purchasing artifacts for the remainder of his life.

A looted painting found by US troops in April 1945 in Merkers, Germany, among other Nazi stolen art and gold worth about $2 million. From the National Archives.

The issue of stolen cultural artifacts isn’t just an international one. In 1990, the US passed the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, requiring all federal agencies and any institutions that receive federal funding to return Native American, Native Alaskan, and Native Hawaiian cultural items from their collections. These items include Indigenous human remains, funerary items, sacred objects, and items having ongoing historical, traditional, or cultural importance central to the group or culture itself. When the law was passed, Congress estimated it would take approximately 10 years to return all cultural objects to their descendants and/or tribes. 33 years later, over 110,000 Native American, Native Alaskan, and Native Hawaiian human remains are still held by federal agencies, museums, and universities. Learn more from the ProPublica article, America’s Biggest Museums Fail to Return Native American Remains.

Our national museum, the Smithsonian, was established in 1846 thanks to a bequest of $508,318 from James Smithson, an Englishman who never even visited the US. His directive was, “to found at Washington, under the name of the Smithsonian Institution, an establishment for the increase and diffusion of knowledge among men.”  Their first collection was a group of European prints and art books, acquired from Vermont Congressman George Perkins Marsh in 1849. However, construction of the first Smithsonian Institution building (seen here to the right) – known as the Castle – wasn’t completed until 1855. Currently, the Smithsonian is the world’s largest museum, education, and research complex, and includes the National Zoo and 19 individual museums (not yet including the new National Museum of the American Latino and the Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum). The current number of objects, art, and specimens in the Smithsonian collection are estimated to be almost 155 million.

Their first collection was a group of European prints and art books, acquired from Vermont Congressman George Perkins Marsh in 1849. However, construction of the first Smithsonian Institution building (seen here to the right) – known as the Castle – wasn’t completed until 1855. Currently, the Smithsonian is the world’s largest museum, education, and research complex, and includes the National Zoo and 19 individual museums (not yet including the new National Museum of the American Latino and the Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum). The current number of objects, art, and specimens in the Smithsonian collection are estimated to be almost 155 million.

Though we too have several buildings that we manage, our collection is merely a fraction of that size! When we want to acquire an object, our collections staff, board, and collections committee have a process by which accession is completed, making sure the object fits well with our current mission and history, and whether we can properly store and care for the object. Some Heritage Square collection facts and figures for you:

-

- We have over 3,000 objects, photographs, and documents in our collection, much of which is on display in Rosson House itself. Some objects are stored there but aren’t on display (kept in closets, cabinets, dressers, etc.), and the remaining are stored in what was once the bedrooms of the Stevens-Haustgen House.

- Almost 5% of the objects we have are doilies, which Victorians used as ornamental mats to protect their furniture (along with antimacassars, piano scarves, furniture scarves, tables cloths, and more).

- We have 80 bottles in our collection, including bottles for condiments, medicines, perfume, nursing, etc. Several of these were found during restoration and/or the archaeological excavation of the area. Stay tuned for a blog we’ll have later this Spring to learn more about some of our antique patent medicine bottles!

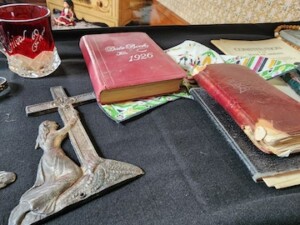

- There are 165 books in our collection – music books, children’s books, medical books, textbooks, novels, and more, including most of Jane Austin’s books (all printed in 1898).

- What little jewelry we have in our collection is period accurate, but is also costume jewelry. No diamonds here, Hope or otherwise!

- Sometimes objects found in our collection are a bit of a revelation! One recent surprise: While the Museum was closed in the summer of 2020 and our staff did a whole-house clean, they found an item that was donated in the 1980s as a footwarmer, but it was actually a World War II German anti-tank mine. It had been deactivated sometime in the past, but we called the authorities in, just to make sure.

- Around two dozen of the objects in our collection belonged to the families who lived at Heritage Square (with many more family photographs and documents).

Most of the objects are on display at Rosson House – particularly in the Silva exhibit, which you should definitely stop by and see if you haven’t already.

Most of the objects are on display at Rosson House – particularly in the Silva exhibit, which you should definitely stop by and see if you haven’t already.

What Is It??

Here are a few things from our collection you may or may not be familiar with, but can you guess? Click on the names to learn more:

-

Combination

A piece of women’s underclothing which combined chemise and drawers into one garment.

-

Epergne

An ornate, tiered centerpiece for the dining table that would hold flowers, candles, and/or food.

-

Firkin

A small wooden vessel or cask used for storing liquids (like beer!), butter, and sometimes fish.

A small wooden vessel or cask used for storing liquids (like beer!), butter, and sometimes fish. -

Lambrequin

A curtain or drapery covering the upper part of a door or window, or suspended from a shelf.

Extra Credit – From Medieval times, a lambrequin is also a heraldry or woven fabric covering for a helmet to protect it from heat, rust, etc.

-

Potichomanie Ball

Also known as memory balls, witch’s balls, or Victorian whimsies, potichomanie balls are created with a process similar to decoupage – printed paper motifs are cut out and glued on the inside of a clear glass ball. Paint would be applied on the inside of the ball after the glue was dry to create a finished piece that looked like painted china.

Also known as memory balls, witch’s balls, or Victorian whimsies, potichomanie balls are created with a process similar to decoupage – printed paper motifs are cut out and glued on the inside of a clear glass ball. Paint would be applied on the inside of the ball after the glue was dry to create a finished piece that looked like painted china. -

Stevengraph

A picture woven from silk, popular during the Victorian Era, and created by and named after Thomas Stevens. The Stevengraph in our collection (currently in storage) is a memorial portrait of President William McKinley, who was assassinated in 1901.

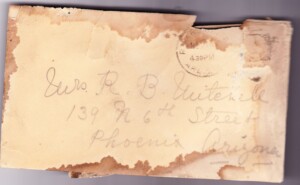

The envelope of the letter found in Rosson House during restoration.

You can find information on how to preserve your own collection of important family photographs, documents, and objects from the American Library Association’s Preservation Week website, under Saving Your Stuff. Learn about collections stewardship and museum collections ethics from the American Alliance of Museums.

Information for this blog article was found through the links included above, as well as from the Heritage Square archives; the National Park Service – Facilitating Respectful Return and The Scope of Museum Collections; the Charleston Museum website; the Smithsonian website; the Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum – The Marsh Collection; The Conversation – “Hidden women of history: Ennigaldi-Nanna, curator of the world’s first museum”; the National Museum of the American Indian; the Art Newspaper – “Smithsonian adopts new ‘ethical returns policy’ to handle artefacts with problematic histories”, the National Archive – Nazi Looted Art; and the New York Times – “This Art Was Looted 123 Years Ago. Will It Ever Be Returned?”.

Archive

-

2024

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-