The Great Migration: Indiscernibles in Arizona

Learn more about The Great Migration: Indiscernibles in Arizona, courtesy of guest curator Clottee Hammons of Emancipation Arts, LLC.

-

The Jim Crowe Legacy In The Valley of the Sun

“Despite the very recent focus on equity, the specter of Jim Crowe segregation is still present in the Valley of the Sun. Just because the term seems antiquated does not mean that the fundamental practices of discrimination in housing, employment, education and health care have subsided for Black Arizonans.”

Learn more about how Jim Crowe is still affecting our lives every day by reading this article by Clottee Hammons, Creative Director of Emancipation Arts.

-

AZ PBS Interview with Clottee Hammons

See the Arizona PBS Horizonte interview with Guest Curator, Clottee Hammons as she talks about her exhibit, The Great Migration: Indiscernibles in Arizona.

-

Our Interview with Clottee

Please tell us about yourself — what is your background?

I’m a second-generation Arizonan. I grew up in the segregated downtown Phoenix area and attended kindergarten at Monroe School; where I had my first solo art exhibition. Even though I was only five years old that experience probably defined my future in the Arts as much as any academic experience or influence. I remember my teacher, Miss Anderson, fondly and every time that I pass my old school, I’m thrilled that it’s still standing and is now The Children’s Museum.

What role do you feel an artist like yourself has in society?

I am a mixed media artist working in recycled materials, fabric, pencil, crayon, watercolor and acrylic paint. The statement I am trying to make, determines the medium. I also write poems, essays, short stories and snarky letters.

Very often artists are cast in the role of political agitators, truth-tellers, cultural preservationists and influencers. In reality, an artist can be all of those things at varying points in their career.

Not everyone is trying to understand beyond a seven second visual experience. Arts organizations are often discriminatory and elitist, so it’s incumbent upon the artist to be as informed and intentional about their work as possible.

What is your personal connection with Heritage Square?

As I said, I went to kindergarten across the street and I also attended St. Mary’s Grammar School and St. Mary’s High School … so I walked past it every day on the way to and from school for 13 years. It feels like coming full circle to have an exhibition in a place that I could only admire from the outside.

What was the initial inspiration behind your exhibit, The Great Migration: Indiscernibles in Arizona?

Black Arizonans have been omitted from the historical narrative of the state, and this has troubled me since the time of my earliest academic experiences. When we travel to other states or encounter Black people from places that are more readily acknowledged as part of The Great Migration, there is a stigma attached to being a Black Arizonan. I’ve endeavored to teach my son and grandchildren that we have nothing to be ashamed of because we are from Arizona. I’ve tried to teach as many people as possible about how Black people came to live in Arizona; because I knew that they would not learn it in school.

The more I studied, the more I realized that the people locally recognized as “historians” were sharing fragmented and myopic narratives that repeatedly referred to the same Black men and downplayed Jim Crow.

I am an Arizonan and the omissions were exasperating. This has literally been in me for a lifetime.

How has your position/perspective as an artist helped you pull together all the people involved in this project?

I created The Emancipation Marathon to honor my African ancestors. It is a literary marathon that commemorates the enslaved African victims of American chattel slavery. Because it is a long-running tradition that relies on community participation, I’ve been able to meet people and literally solicit stories.

What was the most challenging part of developing this exhibit? What was the most rewarding?

Not becoming discouraged.

Opening night at Arizona State University School of Human Evolution and Social Change. The enthusiasm and glowing pride of people that walked through it was incredible.

What was the most surprising revelation for you from the oral histories your student volunteers conducted?

It wasn’t necessarily surprising but the most prevalent and consistent theme that I find throughout the interviews that the students conducted, interviews that I’ve conducted and general conversations with Black people that move here from other states; is that there is a constant search for Black culture, community and commerce. For many Black people living in Arizona there is a very strong sense of estrangement and constantly seeking places to ‘belong”.

What is your vision for this exhibit? What outcomes would you like to see happen?

This is a traveling exhibition and will go throughout the state expanding on Arizona history. I’m working on a guide for teachers to accompany the visual experience. I hope that educators will begin to look in their classrooms and realize more fully whose stories are not being told. I also hope that Black students will be inspired to independently pursue knowledge and gain a greater appreciation of their place in the state and society.

Another outcome will be the ongoing process of youth learning interviewing and archiving skills through relationship-building sessions with senior citizens.

There is also a plan underway for inclusion in the public arts processes that does not rely on non-inclusive methodologies.

How does your work in this exhibit comment on current social issues?

This exhibition addresses many issues:

-

- The stigma of being a Black Arizonan

- Displacement and estrangement of Black communities in Arizona

- Cultural competency failures of the education system

- Preserving the legacy and acknowledging the contributions of Black music performers

- The lack of Blacks in public arts selection process and commissions

- Methods of bridging generation gaps and honoring our ancestors

… to name a few.

-

-

About Dr. Lowell C. Wormley - Physician and Community Builder

Dr. Wormley was born on November 4 1906 in Washington, D.C. to Mamie Louise Cheatham Wormley and G. Smith Wormley, who was then the principal of Randall Junior High School, Washington, D.C. Both of Dr. Wormley’s parents came from longstanding, well-known Washington, D.C. families.

Dr. Wormley was born on November 4 1906 in Washington, D.C. to Mamie Louise Cheatham Wormley and G. Smith Wormley, who was then the principal of Randall Junior High School, Washington, D.C. Both of Dr. Wormley’s parents came from longstanding, well-known Washington, D.C. families.His paternal great-grandfath

er, James Wormley, owned a hotel in Washington, D.C. at 15th & H Sts. It was there that Charles Sumner lived and died, and it was also there that the Wormley House Agreement took place in 1877, an agreement that settled the Presidential election in 1876. Dr. Wormley’s maternal grandfather, Henry Plummer Cheatham, a Republican Congressman from North Carolina, also lived in the district. Dr. Wormley was graduated from Dartmouth College in 1927 where he stayed on for a two-year course of medical education. He then returned to Washington to complete his four years of medical training at the Howard University Medical School, where he finished with honors in 1931. He did his residency at Harlem Hospital in New York City, where he practiced until he joined the U.S. Army in 1941.

In World War II, Dr. Wormley served as Captain in the Medical Corps at Fort Huachuca Regional Hospital. Following his honorable discharge from the Army, he was appointed Senior Medical Officer in charge of surgery at Poston Regional Hospital in Parker, Ariz. In 1946, he began the practice of medicine in Phoenix, a practice he continued for almost 40 years.

Dr. Wormley was also engaged in numerous civic activities. He served on the staff of eight Phoenix hospitals as Chairman of the Board of the Arizona State Hospital. He also served on the boards of the Arizona Medical Society, the Salvation Army and the Maricopa Council of Campfire Girls of Arizona. He was a life member of the NAACP and served on the Board of the Phoenix Chapter. He also served as President of Phoenix Chapter of Dartmouth Alumni and was honored for his successful efforts to have his alma mater enroll American Indians, for whom Dartmouth College was originally established.

The Phi Iota Chapter of Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Incorporated, made its debut on October 1, 1946. Under the leadership of Dr. Lowell Wormley, Ernest Bartlett, and the late George Meares, six interested men traveled to Los Angeles, California and organized the Phi Iota Chapter. The six young pledgees were: William Warren, John Henry, Denzil Perdue, Dr. David Solomon, Lloyd Dickey and the Honorable H.B. Daniels.

Dr. Lowell Wormley served as the first Basileus and helped initiate many good Omega Men. In December of 1947, Phi Iota Chapter hosted the Grand Conclave in Phoenix at the Del Webb Townhouse. Brothers from all over the country visited Phoenix for the first time.

Dr. Wormley passed away on Saturday, January 18, 1986 at the Scottsdale, Arizona Convalescent Plaza.”

This article was taken from Emancipation Arts Facebook Page

-

Home Remedies - Driven by Necessity

Recollection of a Potent Remedy

Recollection of a Potent RemedyHog Hoof Tea was a popular home remedy for a wide range of illnesses including the common cold which was utilized across the American South. There are records of its use among enslaved Africans prior to the Civil War.

It was kept on the back of the stove with the spices and drippings container. I don’t know if the hoofs were naturally black or if they were burned black, but they resembled garlic clove shaped pieces of charcoal. Two pieces were boiled and then removed from the fire and covered. The “tea” was strained and served piping hot. This treatment was repeated as needed. The thought of another cup, I’m sure, contributed to many speedy recoveries.

Many recipes used in past and current home remedies bear the distinctive influence of enslaved Africans. On plantations it was simple pragmatism treat illnesses and injuries of commodified Africans. Personnel that treated the enslaved could be physicians, plantation “mistresses”, overseers or other enslaved people. Distrust of white doctors was justified by the gory experiments freely conducted on enslaved people with no recourse to object. Dr Marion Sims perfected gynecological surgery on the enslaved. He used drugs causing addictions in order to immobilize the women. Hundreds of enslaved Africans in 1800 (including 200 of Thomas Jefferson’s slaves) were given smallpox in order to test how safe the new vaccine was. Dr Thomas Hamilton is known for placing slaves in open pits with their heads were above ground, supposedly in order to test what medication permitted someone to withstand a high temperature. Logically Blacks preferred to be treated by other Blacks or treat themselves. They would often conceal their illnesses even if it meant they would be punished if the slave-holder found out.“When the 1918 influenza epidemic began its deadly tour across the United States, African Americans were already beset by a host of major public health, medical, and social problems that shaped how they experienced the epidemic and how the epidemic affected them. By 1918, medical and public health reports had documented that African Americans suffered higher morbidity and mortality rates than white people for several diseases. The Atlanta Board of Health, for example, reported in 1900 that the black death rate exceeded that of the white death rate by 69%. In an analysis of the 1900 census, W.E.B. Du Bois, the influential sociologist and civil rights activist, found that African American death rates were two to three times higher than for white people for several diseases including tuberculosis, pneumonia, and diarrheal disease. Although African Americans had lower rates for scarlet fever, cancer, and liver disease, Du Bois concluded, “The Negro death rate is, however, undoubtedly considerably higher than the white.” Home remedy use is an often overlooked component of health self-management

, with a rich tradition, particularly among African Americans and others who have experienced limited access to medical care or discrimination by the health care system.” In 1937 – “The Arizona State Board of Health, in commenting on (cotton pickers) contractors’ camps: Their camps are of a temporary nature, with no provision for proper water supply or sewage disposal and to operate under such conditions should be prohibited by law in the interest of public health and common humanity.” Home remedies can potentially interfere with biomedical treatments. This study documented the use of home remedies among older rural adults, and compared use by ethnicity (African American and white) and gender. A purposeful sample of 62 community-dwell

ing adults ages 65+ from rural North Carolina was selected. Each completed an in-depth interview, which probed current use of home remedies, including food and non-food remedies, and the symptoms or conditions for use. Systematic, computer-assist ed analysis was used to identify usage patterns. Five food and five non-food remedies were used by a large proportion of older adults. African American elders reported greater use than white elders; women reported more use for a greater number of symptoms than men. Non-food remedies included long-available,

over-the-counte r remedies (e.g., Epsom salts) for which “off-label” uses were reported. Use focused on alleviating common digestive, respiratory, skin, and musculoskeletal symptoms. Some were used for chronic conditions in lieu of prescription medications. Home remedy use continues to be a common feature of the health self-management of older adults, particularly among African Americans, though at lower levels than previously reported. While some use is likely helpful or benign, other use has the potential to interfere with medical management of disease. Health care providers should be aware of the use of remedies by their patients.”

Hog Hoof Tea “Recollections of a Potent Remedy” provided by exhibition Curator Clottee Hammons

-

Interview with Big Pete Pearson

See Clottee Hammon’s interview with King of Arizona Blues, Big Pete Pearson.

Listen to Big Pete Pearson and Scotty Spenner play the blues in the Scottsdale Center for the Arts Summer Streams series.

-

African-American Nurses Who Served During WWII

African-American nurses have a long history of serving our country with distinction. Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman cared for the sick and wounded in Union hospitals during the Civil War, and African-American nurses served in the Spanish-American war, as well as the first and second World Wars. In World War II, African-American nurses were sent to care for German POWs at camps across the US, including one here in Florence, AZ.

“On the summer afternoon in 1944 that 23-year-old Elinor Powell walked into the Woolworth’s lunch counter in downtown Phoenix, it never occurred to her that she would be refused service. She was, after all, an officer in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps serving her country during wartime, and she had grown up in a predominantly white, upwardly mobile Boston suburb that didn’t subject her family to discrimination…”

Read more about Elinor’s story in this Smithsonian Magazine article – The Army’s First Black Nurses Were Relegated to Caring for Nazi Prisoners of War.

-

24th Annual Emancipation Marathon

There is no national recognition of the victims of American Chattel Slavery. The Emancipation Marathon is an annual literary marathon, which was established in 1996 and continues to present day.Volunteers read aloud about “that peculiar institution”, American Chattel Slavery, in honor of those victims.

Due to COVID-19 restrictions, the 2020 Emancipation Marathon readings were recorded as part of a partnership between Emancipation Arts LLC, the Scottsdale Center for the Performing Arts, Heritage Square, Local First AZ, and the Virginia G. Piper Center for Creative Writing.

- Borderland Chronicles No. 23 by Cindy Hayostek, 2013 (Excerpt: “Fairfax W. Burnside Fights Segregation in the Douglas Schools System”) — read by Kari Carlisle, executive director, Heritage Square

- Slavery Defended: The Views of the Old South, 1963 (Excerpt: “Cotton is King” by David Christy) — read by Diandra Adamczyk, senior programming coordinator, Scottsdale Center for the Performing Arts

- How Mass Produced and Widely Distributed Images Helped the Abolitionist Movement by Frank H. Goodyear, III (Excerpt: “The Scourged Back: How Runaway Slave and Soldier Private Gordon Changed History”) — ready by Rashaad Thomas, poet

- “The Slaver” from John Brown’s Body by Stephen Vincent Benet, 1927 (Excerpt: “Prelude”) — read by Greg Esser, vice president, Roosevelt Row Corp.

- Africans in America by Charles Johnson, Patricia Smith, and the WGBH Series Research Team (Excerpt: “Martha’s Dilemma”) — read by Jennifer Hance, director of education, Heritage Square

- The African American Experience in Tempe by Jared Smith, 2010 (Excerpt: Chapters 2 and 3) — read by Nicole Underwood, author

- We Are Who We Say We Are: A Black Family’s Search Home Across the Atlantic World by Mary Frances Berry, 2015 (Excerpt: “Becoming Colored Creole”) — read by Miguel Monzon, curator, Modified Arts

- Sons of Mississippi by Paul Hendrickson, 2003 (Excerpt: “Grimsley”) — read by Scotty Spenner, musician

- The Slave Trade by Hugh Thomas, 1997 (Excerpt: “Sharks Are the Invariable Outriders of All Slave Ships”) — read by Ahmad Daniels, author

- “How Native American Slaveholders Complicate the Trail of Tears Narrative” by Ryan P. Smith (Smithsonian magazine, 2018) — read by Neal Lester, professor of English literature

- 50 Essays: A Portable Anthology, 2004 (Excerpt: “Aren’t I A Woman?” by Sojourner Truth) — read by Sharla Johnson, minister (who also performed an a cappella rendition of “Lift Every Voice and Sing”)

- A Wreath for Emmet Till by Marilyn Nelson, 2005 (Excerpt: “Forget him not. Though if I could, I would.”) — read by Gabriel Bey, musician (who also performed “Lift Every Voice and Sing” on trumpet)

- Organized Labor & The Black Worker (Excerpt: Chapter 1 from “Slavery to Freedom”) — read by Julie Petersen, playwright

- The Battle of Negro Fort: The Rise and Fall of a Fugitive Slave Community, Matthew J. Clavin, 2019 (Excerpt: “The British Post on Prospect Bluff”) — read by Matt Herman, healthcare professional

- American Slavery 1619–1877 by Peter Kolchin, 2003 (Chapter 4) — read by Keith Johnson, musician (who also performed “Lift Every Voice and Sing” on steel drum)

- Not All Okies Are White | The Fabric of Black Life by Geta LeSeur, 2000 (Excerpt: pp. 97–102) — read by Jason Landrum Jr., health insurance professional

- The Devaluation of Assets in Black Neighborhoods | The Case for Residential Property by Andre Perry, Jonathan Rothwell, David Harshbarger, 2019 — read by Matthew Aguilar, director of events, Heritage Square

- White Fragility by Robin Diangelo, 2018 (Excerpt: “The Challenges of Talking to White People About Racism”) — read by Brian Passey, senior communications specialist, Scottsdale Arts

- America’s War: Talking About the Civil War and Emancipation on Their 150th Anniversaries, edited by Edward L. Ayers, 2012 (Excerpt: “What to the Slave is the 4th of July” by Frederick Douglas, July 5, 1852) — read by Jason Landrum Sr., truck driver

- The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and American Capitalism by Edward Baptist, 2014 (Excerpt: “Left Hand”) — read by Clottee Hammons, creative director, Emancipation Arts

-

A Step Up From Slavery

Historically, a portion of Arizona’s economy was built on the growth and success of the cotton industry. But what has long been overlooked is the strength and endurance of the workers who toiled in the extreme Arizona heat, picking cotton while facing the hazards of heatstroke and rattlesnakes alongside the greater threat of racism and segregation.

Historically, a portion of Arizona’s economy was built on the growth and success of the cotton industry. But what has long been overlooked is the strength and endurance of the workers who toiled in the extreme Arizona heat, picking cotton while facing the hazards of heatstroke and rattlesnakes alongside the greater threat of racism and segregation.Read more about these workers and their forgotten history in the Arizona Mirror article, “The ‘historical silence’ of the Black workers who made Phoenix prosperous.”

(Picture of cotton fields from Phoenix Magazine)

-

The 14th Amendment

The 14th Amendment to the US Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, during the Reconstruction era. One of the most important amendments ever crafted, it addresses citizenship rights and equal protection under the law, and was created in response to issues related to how African Americans were treated following the Civil War.

Read more about it in this article.

-

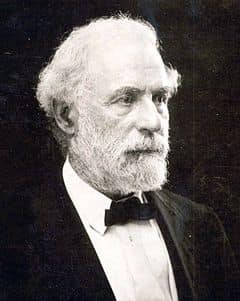

The Truth About Robert E. Lee

Emancipation Arts’ Motto: “I promise you will learn what schools will not teach.”

The myth of Lee goes something like this: He was a brilliant strategist and devoted Christian man who abhorred slavery and labored tirelessly after the war to bring the country back together.

There is little truth in this. Lee was a devout Christian, and historians regard him as an accomplished tactician. But despite his ability to win individual battles, his decision to fight a conventional war against the more densely populated and industrialized North is considered by many historians to have been a fatal strategic error.

When Lee wrote his letter to The Times (published on Jan. 8, 1858)

he was an accomplished United States Army officer acting as the executor of his father-in-law’s will. His wife, Mary Anna Custis Lee, a descendant of Martha Washington, had recently inherited her father’s estate, Arlington House, along with the slaves who lived there.In his will, Ms. Lee’s father, George Washington Parke Custis, said his slaves should be freed five years after his death. Mr. Custis, while dying, told his slaves that they should be freed immediately, rather than five years on.

But an article that was first published by The Boston Traveler and reprinted in The Times on Dec. 30, 1857, contended that the slaves “will be consigned to hopeless Slavery unless something can be done” because Mr. Custis’s heirs did not want to free them.The 1857 article in The Times noted that slaves’ own voices were missing from the story of Mr. Custis’s dying wishes. It said that when he told his slaves they would be freed, “no white man was in the room, and the testimony of negroes will not be taken in Court.”

In 1862, in accordance with Mr. Custis’s will, Lee filed a deed of manumission to free the slaves at Arlington House and at two more plantations Mr. Custis had owned, individually naming more than 150 of them. And in January 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring that all people held as slaves in the rebelling states “are, and henceforward shall be free.”

Years later, in 1866, one former slave at Arlington House, Wesley Norris, gave his testimony to the National Anti-Slavery Standard. Mr. Norris said that he and others at Arlington were indeed told by Mr. Custis they would be freed upon his death, but that Lee had told them to stay for five more years.

So Mr. Norris said he, a sister and a cousin tried to escape in 1859, but were caught. “We were tied firmly to posts by a Mr. Gwin, our overseer, who was ordered by Gen. Lee to strip us to the waist and give us fifty lashes each, excepting my sister, who received but twenty,” he said. And when the overseer declined to wield the lash, a constable stepped up, Mr. Norris said. He added that Lee had told the constable to “lay it on well.”

But even if one conceded Lee’s military prowess, he would still be responsible for the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Americans in defense of the South’s authority to own millions of human beings as property because they are black.

Lee’s elevation is a key part of a 150-year-old propaganda campaign designed to erase slavery as the cause of the war and whitewash the Confederate cause as a noble one. That ideology is known as the “Lost Cause”, and as the historian David Blight writes, it provided a “foundation on which Southerners built the Jim Crow system.Of all the letters by Lee that have been collected by archivists and historians over the years, one of the most famous was written to his wife. Lee was a slave owner—his own views on slavery were explicated in that 1856 letter that is often misquoted to give the impression that Lee was some kind of abolitionist. In the letter, he describes slavery as “a moral & political evil,” but goes on to explain that:

“I think it however a greater evil to the white man than to the black race, & while my feelings are strongly enlisted in behalf of the latter, my sympathies are more strong for the former. The blacks are immeasurably better off here than in Africa, morally, socially & physically. The painful discipline they are undergoing, is necessary for their instruction as a race, & I hope will prepare & lead them to better things. How long their subjugation may be necessary is known & ordered by a wise Merciful Providence. Their emancipation will sooner result from the mild & melting influence of Christianity, than the storms & tempests of fiery Controversy.”The argument here is that slavery is bad for white people, good for black people, and most important, better than abolitionism; emancipation must wait for divine intervention. That black people might not want to be slaves does not enter into the equation; their opinion on the subject of their own bondage is not even an afterthought to Lee. White supremacy does not

“violate” Lee’s “most fundamental convictions.” White supremacy was one of Lee’s most fundamental convictions.Lee had beaten or ordered his own slaves to be beaten for the crime of wanting to be free; he fought for the preservation of slavery; his army kidnapped free black people at gunpoint and made them unfree—but all of this, he insisted, had occurred only because of the great Christian love the South held for black Americans. Here we truly understand Frederick Douglass’s admonition that “between the Christianity of this land and the Christianity of Christ, I recognize the widest possible difference.”

Read more about racism and Robert E. Lee in these articles from The Atlantic and The New York Times.

The Mission of Emancipation Arts is to honor our enslaved African ancestors through Arts practices, dissemination of relevant history and egalitarian collaborations.

Find more information about Emancipation Arts on their webpage.