Telephones at the Turn-of-the-Century

Did you know…

People have been communicating with each other for millions of years, sometimes more effectively than others. Once spoken language and the written word were created, the main struggle (outside of familial communications!) was with communicating effectively over distance. With the advent of the postal service people could write to each other, but the sheer size of the United States proved to be a stumbling block – even with railroads and the Pony Express, mail still took time to be delivered. You could send a letter to a loved one and it could be weeks until it was delivered, or even longer.

People have been communicating with each other for millions of years, sometimes more effectively than others. Once spoken language and the written word were created, the main struggle (outside of familial communications!) was with communicating effectively over distance. With the advent of the postal service people could write to each other, but the sheer size of the United States proved to be a stumbling block – even with railroads and the Pony Express, mail still took time to be delivered. You could send a letter to a loved one and it could be weeks until it was delivered, or even longer.

Enter the telegraph, invented in the 1830s by Samuel Morse, and first put into operation with Morse Code between Washington, DC and Baltimore, MD on May 24, 1844. It revolutionized long distance communication, but was still limited to those who had a telegraph set connected to the outside world, and a working knowledge of Morse Code.

–. — … …. / -.. .- .-. -. / .. – !

-

You had us at Ahoy!

Before the invention of the telephone, if you were going to call someone it meant that you would “call on” them, or go visit them at their home or place of business. Special calling cards were made – approximately the size and shape of a business card today – that would have your name inscribed on them (and title, if applicable). When the telephone was invented, “calling” got a whole new definition, and a corresponding greeting. There was no set way to greet someone when you phoned them, or when you received a phone call. People would often say, “Are you there?” and “Do I get you?” when calling or answering a call (reminding us of those commercials from a decade or more ago with their incessant, “Do you hear me now?”). Alexander Graham Bell preferred using the word, “Ahoy!” when answering a call, but the world (unfortunately, in our opinion) settled on a simple, “Hello.”

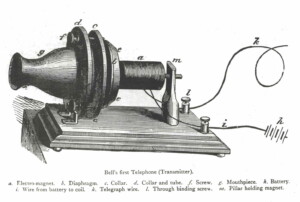

Several inventors explored how to somehow project a person’s voice across distance instead of just their transcribed words, including Antonio Santi Giuseppi Meucci, an Italian immigrant who began developing the design of a talking telegraph or telephone in 1849; and Elisha Gray, a professor at Oberlin College (Ohio), who applied for a telephone patent the same day Alexander Graham Bell did (February 14, 1876). The final results are controversial – Bell received the patent (drawn by inventor and patent draftsman, Lewis Latimer, who you can read about under the Bright Ideas heading of our article on Electricity), but there may have been impropriety on the part of the patent officer or from Bell himself. He made the first telephone call a month after filing his patent, famously saying, “Mr. Watson, come here. I want to see you.”

Regardless of who invented the telephone, it became popular fairly quickly. Customers would rent or purchase a phone and get a subscription for service. An operator could only connect those who subscribed to each other, as they were the only phones directly connected to the company’s switchboard. The earliest telephone operators were young men, who were evidently rude to each other and their customers. They were soon replaced with young women, though, who not only didn’t swear at people like the boys did, but also did the job better and faster.

-

A Creepy Conversation

How does a ghost answer the phone?

How do you boooooo!

(sorry, we couldn’t resist)A couple of well-known turn-of-the-century inventors also experimented with creating a machine that would allow people to talk with their dead loved ones.

When Nikola Tesla was tinkering with a crystal radio in 1901, it picked up what were likely very low frequency radio signals from atmospheric disturbances (like solar flares) and from household electricity. The sounds scared him, as he wrote in his diary, “”My first observations positively terrified me, as there was present in them something mysterious, not to say supernatural, and I was alone in my laboratory at night.” He would continue to do similar experiments, and was never sure where those voice-like sounds were coming from.

Thomas Edison heard of Tesla’s experiments and was competitive enough to try and make a machine of his own that could contact the dead. Inspired by the theories of Albert Einstein on special relativity and quantum entanglement, Edison believed that if mass converts into energy, then perhaps the same thing could happen to the spirits of people when they die, and then that energy can go on to interact with the physical world. An interesting idea to be sure, but his experiments with his machine – what he called a spirit phone – didn’t pan out, even when he and a friend made an agreement that the first to die would contact the other. No such phone call was made!

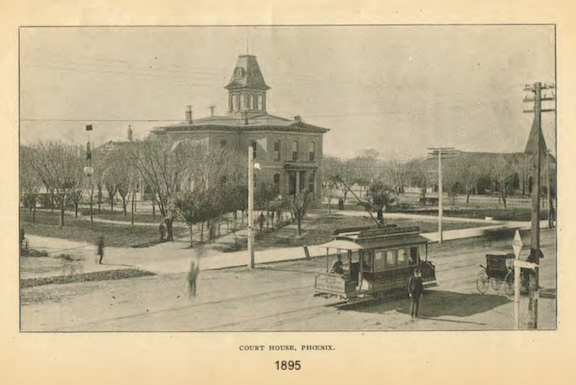

President Rutherford B. Hayes had the first phone installed in the White House in 1877, and the phone number there was 1. The only phone it could call or be called by was the Treasury (because they had the only other phone in the area, which we’re assuming was designated 2). Early the next year, Lieutenant Philip Reade (acting Signal Officer in charge of the US Military Telegraph) was testing a phone and connection from Yuma, AZ to San Diego, CA. He was successful by mid-March 1878. Tucson opened up its telephone exchange exactly 140 years ago from the exact publication of this article (seriously, no joke!), and though we’ve heard that Phoenix had a telephone company by 1886, we can’t find them listed in the Phoenix Business Directory two years later. However, an article from the July 18, 1891 Arizona Republican said that telephone wires were laid in to connect 25 phones, and that 45 more remained to be connected. The Telephone office was fully open and operational (like a Death Star) by July 21st, with posted hours of 8am to 8pm daily. The newspaper reminded customers that a list of subscribers would be placed in every office, and that two rings on their telephone meant the central office was contacting them.

We know the occupants of Rosson House enjoyed the convenience of having a telephone because of the letters written by Whitelaw Reid said so. The phone that is currently there in the back hallway by the carriage door (on the south side of the House) is not original to the home, but is from the same time period, and was donated to Heritage Square during the restoration of Rosson House. When it was installed, workers discovered the four screw holes from the phone matched up exactly with four old wooden pegs found in the plaster wall, suggesting that the “new” phone was likely very similar to the original one! At least one of the smaller homes at Heritage Square (now the museum store) had a telephone by 1917 (and probably sooner), and we even know that the number was 1585, thanks to a listing placed by Anna Haustgen in the newspaper advertising her dressmaking skills. We also know the Gammel’s phone number there at Rosson House from a newspaper ad, this time from September 1914, announcing “Nicely furnished rooms” for rent and asking interested parties to call 8803.

We know the occupants of Rosson House enjoyed the convenience of having a telephone because of the letters written by Whitelaw Reid said so. The phone that is currently there in the back hallway by the carriage door (on the south side of the House) is not original to the home, but is from the same time period, and was donated to Heritage Square during the restoration of Rosson House. When it was installed, workers discovered the four screw holes from the phone matched up exactly with four old wooden pegs found in the plaster wall, suggesting that the “new” phone was likely very similar to the original one! At least one of the smaller homes at Heritage Square (now the museum store) had a telephone by 1917 (and probably sooner), and we even know that the number was 1585, thanks to a listing placed by Anna Haustgen in the newspaper advertising her dressmaking skills. We also know the Gammel’s phone number there at Rosson House from a newspaper ad, this time from September 1914, announcing “Nicely furnished rooms” for rent and asking interested parties to call 8803.

By 1914, there was one working telephone for every ten people in the United States. By the end of World War II 30+ years later, that number had been halved, with one phone for every five people. We reached the distinctive milestone of a 1:1 telephone to people ratio in the US in 1998. As of 2017, though, that number had reached 1.4 phones to every person – three quarters of them were cell phones, 10% were landlines, and the remainder were internet enabled phones. Scientists estimate that we will spend approximately nine years of our lives on our phones. Thanks for spending some of that time reading this blog!

P.S. – The Morse Code message at the top of the page reads, “Gosh darn it!”

Information for this article was found on PBS American Experience – The Telephone; Forbes Magazine; the Library of Congress Digital Newspaper Archive and Everyday Mysteries; Merriam Webster; the Arizona Memory Project; and The Conversation

Learn about the history of the Pony Express from the National Park Service website. They even have links to stories, places and exhibits along the trail you can visit, and a map that can show you how to take a drive following along the path of the trail!

Explore the National Museum of Science & Technology (Milan, Italy) exhibit, A Brief History of the Telegraph, on Google Arts & Culture. It has a picture of an amazing telegraph machine that used keys like a piano to type out messages.

Archive

-

2025

-

January (1)

-

-

2024

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-