Sleep On It: How Turn-of-the-Century Phoenix slept outside

Posted November 1, 2024

Written by Heather Roberts, Research Historian

For a printable, PDF version of this article, please click here.

Did you know…

After Phoenix endured over 100 days of temperatures in the three-digits this year, not to mention 70 days at or over 110°, and 21 consecutive days of record heat in October alone (!!), it feels timely to revisit the issue of how people in the Arizona Territory were able to live here, entirely without the luxury of air conditioning. Without AC, solar gain heats up buildings enough throughout the day so that it’s hotter inside at night than it is outside. So for many, sleeping outdoors made more sense.

After Phoenix endured over 100 days of temperatures in the three-digits this year, not to mention 70 days at or over 110°, and 21 consecutive days of record heat in October alone (!!), it feels timely to revisit the issue of how people in the Arizona Territory were able to live here, entirely without the luxury of air conditioning. Without AC, solar gain heats up buildings enough throughout the day so that it’s hotter inside at night than it is outside. So for many, sleeping outdoors made more sense.

“(In Phoenix) the nights are agreeably cool and pleasant, so that those who sleep outside need a blanket.”

– The Weekly Arizona Miner, June 28, 1873

“The residents declare that the nights are delightful, and that sleeping out of doors (in the summer) is about the greatest of human luxuries. They all do it – sometimes in little houses of wire screens constructed around their cots to keep off the flies; but as often simply on a mattress thrown on the piazza.”

– letter from Whitelaw Reid to John Hay, April 7, 1896 (written while he was living at Rosson House)

Looking through Arizona newspapers, there are several articles from the 1870s onward, mentioning that people were sleeping outside during the hot months of the year. And though there were a few that were fairly innocuous, like in the quote from 1873 seen above, most report on the dangers of sleeping outdoors – namely, being robbed. The Arizona Silver Belt reported on July 18, 1891, that, “Thefts and burglaries are alarmingly frequent in Phoenix. During the hot weather people leave their houses open and many people sleep outside; consequently the light-fingered gentry find little difficultly in plying their trade.” Stories included those whose homes or businesses were robbed while their owners slept outdoors, and those whose more-accessible pockets were emptied while they slept outside. Outdoor sleeping also came with the danger of animal encounters, as was discovered by AJ Grice of Globe, who was bitten by a rabid skunk while sleeping on a porch in October 1892. Luckily for him, Louis Pasteur had developed the first rabies vaccine in 1885, and the newspaper reported that Grice went to New York to receive treatment.

Sleeping outside wasn’t just a hot weather trend, though, and became popular across the country in hot and cold weather for another reason – people’s health.

Though there were those who already slept outside in the South and Southwest due to the heat, prior to the second half of the 19th century the prevailing idea was that night air and dampness caused foul-smelling vapors and miasmas that were bad for your health. This meant that most people slept in their homes with the windows and doors tightly shut. But as scientists discovered that bacteria and viruses were the actual cause of illness instead of the air itself, a “fresh air” movement began, even before contagion theory was fully developed. Advocates like Harriet Beecher Stowe and Florence Nightingale encouraged open windows in hospitals for better light and ventilation. The Surgeon General of the US Army during the Civil War, William Hammond, instituted “pavilion” style architecture for battlefield hospitals, separating the sick and injured patients, and allowing for greater air circulation in the buildings. At a time when indoor lighting and heat sources consisted of burning candles, kerosene, oil, wood, and coal – all of which give off fumes and smoke – this could make a significant difference in air quality. This approach was also helpful in the second half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th as the US fought against a deadlier foe – tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis – also known as consumption, phthisis (pronounced thigh-sis), and “the white plague” – is an ancient, highly contagious upper respiratory disease that, according to the CDC, had killed one in seven of all people on earth by 1900. It disproportionately affected urban populations in Europe and the US in the late 19th and early 20th centuries due to overcrowded and inadequate housing conditions with limited air circulation, as well as insufficient sanitation and nutrition. Improving ventilation was discovered as one way to treat the disease, and had the added benefit of lowering the risk of transmission to other people at the same time (which was also true during the 1918 influenza epidemic, and, much more recently, COVID-19). In the home this was as simple as opening windows or spending more time outside, regardless of the weather. If patients and their families could afford it, they would go to a in search of “the cure” at a sanitarium, where basic treatment for the disease included sleeping on screened porches, eating wholesome foods, and taking part in outdoor activities with plenty of fresh air and sunlight. The first sanitariums for patients with consumption were opened in Asheville, NC, in 1875, and Saranac, NY, in 1884, but many more were built in the southwestern United States, where the low relative humidity was deemed beneficial, including in Colorado, New Mexico, and right here in Arizona.

“Here is a region where…health welcomes the afflicted and where strength awaits the weak and debilitated. There is no spot in North America with a climate so conducive to the curing of lung diseases.”

– 1895 Phoenix City Directory

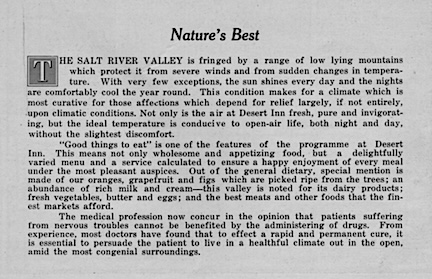

A brochure page from the Desert Inn Sanitarium, located in Phoenix, AZ, c1910.

Pamphlets about health tourism in Arizona were published around this time, touting the territory’s many health clinics, along with its year-round sunlight, dry air, and mild winters. In Health Resorts of the Salt River Valley (1898), the booklet extensively quotes Whitelaw Reid – Ambassador to France (and later, England), editor of the New York Tribune, vice presidential candidate in the 1892 election, and temporary resident of Rosson House for two winters due to “bronchial difficulties” (though not tuberculosis). Reid extoled the sunny weather, mild temperatures, and dry air in Arizona, as well as the availability of cheap, nutritious food – all of which were favored by consumptive clinics as helping treat tuberculosis, like in this promotional brochure from the Desert Inn sanitarium of Phoenix (circa 1910).

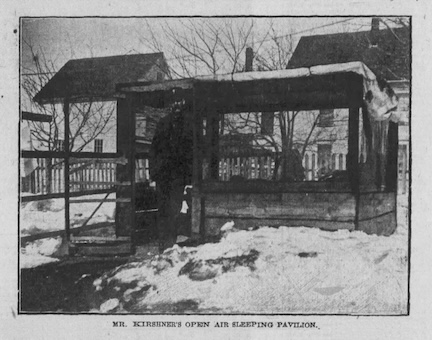

Along with sanitariums that were run by health officials, Arizona saw many less experienced people opening up their homes to health seekers who didn’t have the money to be treated in professional clinics. They would rent rooms, homes, or set up shacks or tents outside for the newcomers, and the locals who cared for them – usually women – would be at a higher risk of falling sick themselves. By the early 1900s, the influx of consumptive patients, also called “lungers”, was overwhelming local resources: a federal public health survey in 1913 reported that half of Tucson’s population travelled there in search of a cure for tuberculosis. Both Phoenix and Tucson issued ordinances directly aimed at health seekers – Phoenix City Ordinance #372 (Aug 14, 1905) prevented construction of tents within city limits. It coincided with an earlier regulation that prohibited people from spitting inside buildings and on the street, as saliva was seen as a primary way to spread disease. This pushed the newcomers to the outskirts of the cities – to Tentville in Tucson (located just northwest of the University of Arizona), and to places like Sunnyslope in Phoenix (a neighborhood located about 8 miles north of Rosson House).

-

Sleeping Porches at the Square

Sleeping Porch: A porch or room having open sides or many windows arranged to permit sleeping in the open air. (via the Merriam-Webster dictionary)

Sleeping Porch: A porch or room having open sides or many windows arranged to permit sleeping in the open air. (via the Merriam-Webster dictionary)Two of the houses at Heritage Square had sleeping porches at one time or another – Rosson House and the Duplex, where we and the City have our offices. The Rosson House balconies were screened in and used for outdoor sleeping at some point. Though we don’t precisely know when this was done, this photo, dated to 1928, shows the front of Rosson House in the background with a screened upper balcony.

The other building at Heritage Square with a sleeping porch, the Duplex (shown below), actually has two – one for each unit. Though both are now currently used for storage, the small porches were screened in with the heavy canvas panels on the outside that could be opened to allow fresh air to come through, like in the second photo below of the Tuberculosis Cabin at Cave Creek Museum.

An ad for pajamas used “for sleeping outside”, from the Arizona Republican newspaper, January 6, 1917.

“Fresh air is as essential in the bedroom at night as during the day, and everyone should sleep with windows wide open during all seasons of the year.”

– Fresh Air and How to Use It, by Dr. Thomas S Carrington (1912)

“From early May to the first of October nearly everybody sleeps outdoors, preferably in the open air, under the stars…”

– Arizona Daily Star, July 19, 1901

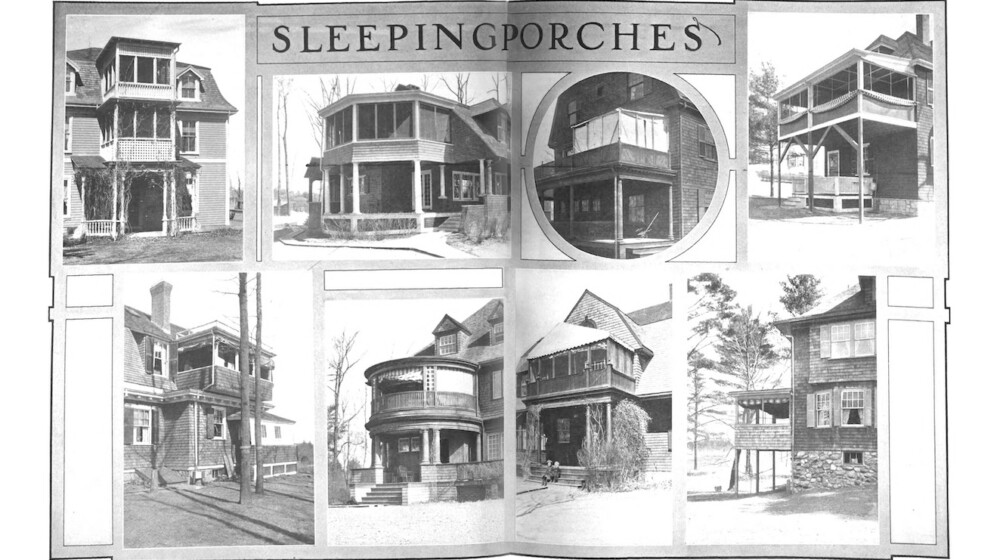

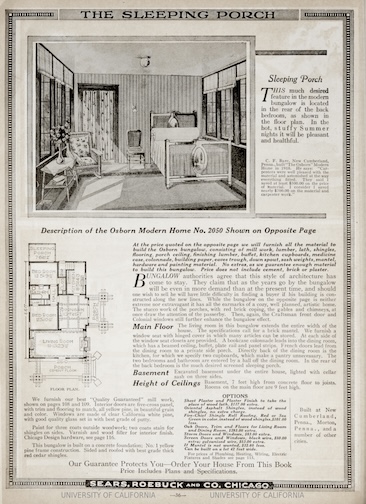

The fresh air movement was so extensive, though, sleeping outside became more popular in the early 20th century, even for people who weren’t sick. Books of architectural floorplans featured sleeping porches (we found them in books from 1900 to 1962), and sometimes even outdoor space for laundry or kitchen work. Popular magazines like Ladies Home Journal and The House Beautiful had floor plans; ads for sleeping porch blinds, furniture, and light fixtures; and also articles about the benefits of and materials needed for adding a sleeping porch to your home. Sleeping porches were included as desirable additions to houses listed for sale or rent in the classified ads sections of Arizona newspapers, as were ads for pajamas meant to be worn when a person slept outside. The “doings around town” section of the Phoenix Tribune would notify readers when their neighbors were improving their homes with sleeping porches. Both Arizona State University in Tempe and University of Arizona in Tucson had outdoor sleeping spaces for their students, and hotels and rooming houses advertised “accommodations for sleeping outside” in local newspapers, too. In Washington DC, the White House got in on the sleeping porch craze in 1910 when President Taft had a stand-alone sleeping porch built on the roof of the executive mansion so that his family had a cooler place to sleep in the summer. Even the 1939 World’s Fair in New York showcased a modern, glass house with a bedroom that converted to a screened sleeping area.

A modern-day sleeping porch, from Southern Living magazine.

Though we continued to find a few real estate ads that included sleeping porches in their listings into the 1990s, they had definitely dwindled in popularity since their peak in the pre-World War II years, and it was a combination of things around the same time led to their demise. In 1944, an antibiotic called streptomycin quickly and successfully cured a patient who had tuberculosis – a huge leap forward in fighting the disease. This also a reduced need for its TB victims to try the “fresh air treatment”. When housing boomed after the war, people built homes as cheaply and as fast as possible, and “extras”, like big, screened porches, were usually scrapped for economic reasons. But it may have been advances in air conditioning in the late 1940s that truly made it possible for people to move beyond sleeping porches.

Sleeping porches might be a thing of the past, but they’re not completely gone. Many century-old homes are being restored, and their sleeping porches are finding new life. And as trends towards outdoor living spaces grow, people are coming back to the realization that having a cool, airy space to spend time, relax, and yes, even sleep, is beneficial.

Information for this article was found in The American Porch – An Informal History of an Informal Place, by Michael Dolan (eBook, 2024); Fresh Air and How to Use it, published by The National Association For the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis (1912); Arizona as a Health Resort, by CLG Anderson (1890); and Health Resorts of the Salt River Valley, published by the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway Passenger Dept (1898); and online through the Library of Congress Chronicling America and Newspapers.com digital newspaper archives; and also at Architectural Digest – How Previous Epidemics Impacted Home Design; AZ Central – A century before coronavirus, Arizona was a haven for…; Brownstoner – A Breath of Fresh Air: A Short History of the Sleeping Porch; Bob Vila – Why We Love the Sleeping Porch; Castle Museum of Saginaw County History – A Porch with a View Towards Health; CDC – History of World TB Day; Harvard Countway Library News & Research – How One Hospital Handled the 1918 Influenza Epidemic; Harvard Library Curiosity Collection – Tuberculosis in Europe & North America (1800-1922); Hennepin History Museum – Hygiene and Housing: The Sleeping Porch in Minnesota; HGTV – All About Post-War Architecture; JSTOR Daily – When Americans Became Obsessed With Fresh Air; JSTOR – From Sleeping Porch to Sleeping Machine: Inverting Traditions of Fresh Air in North America; Pima County Public Library – Health Seekers Haven: Tucson and Tuberculosis; Science Direct – Airborne infection with Covid-19: A historical look at a current controversy; Smithsonian Magazine – Six Innovative Ways Humans Have Kept Cool…; The New England Journal of Medicine – Tuberculosis, Drug Resistance, and the History of Modern Medicine; The White House Historical Association – Sleeping Porch Prior to Solarium; Tucson Historic Preservation Foundation – Tucson Health Seekers: Design, Planning, and Architecture… (PDF); and the US Department of Energy – History of Air Conditioning.

Archive

-

2025

-

January (1)

-

-

2024

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-