Perilous Pins: How Fear of Hatpins Once Gripped the Nation

Posted December 1, 2024

Written by Heather Roberts, Research Historian

For a printable, PDF version of this article, please click here.

Content Warning – This article mentions stories of harassment, assault, grievous bodily injury, and fatalities.

Did you know…

Actress Lily Elise wearing a fashionably large hat, c1907.

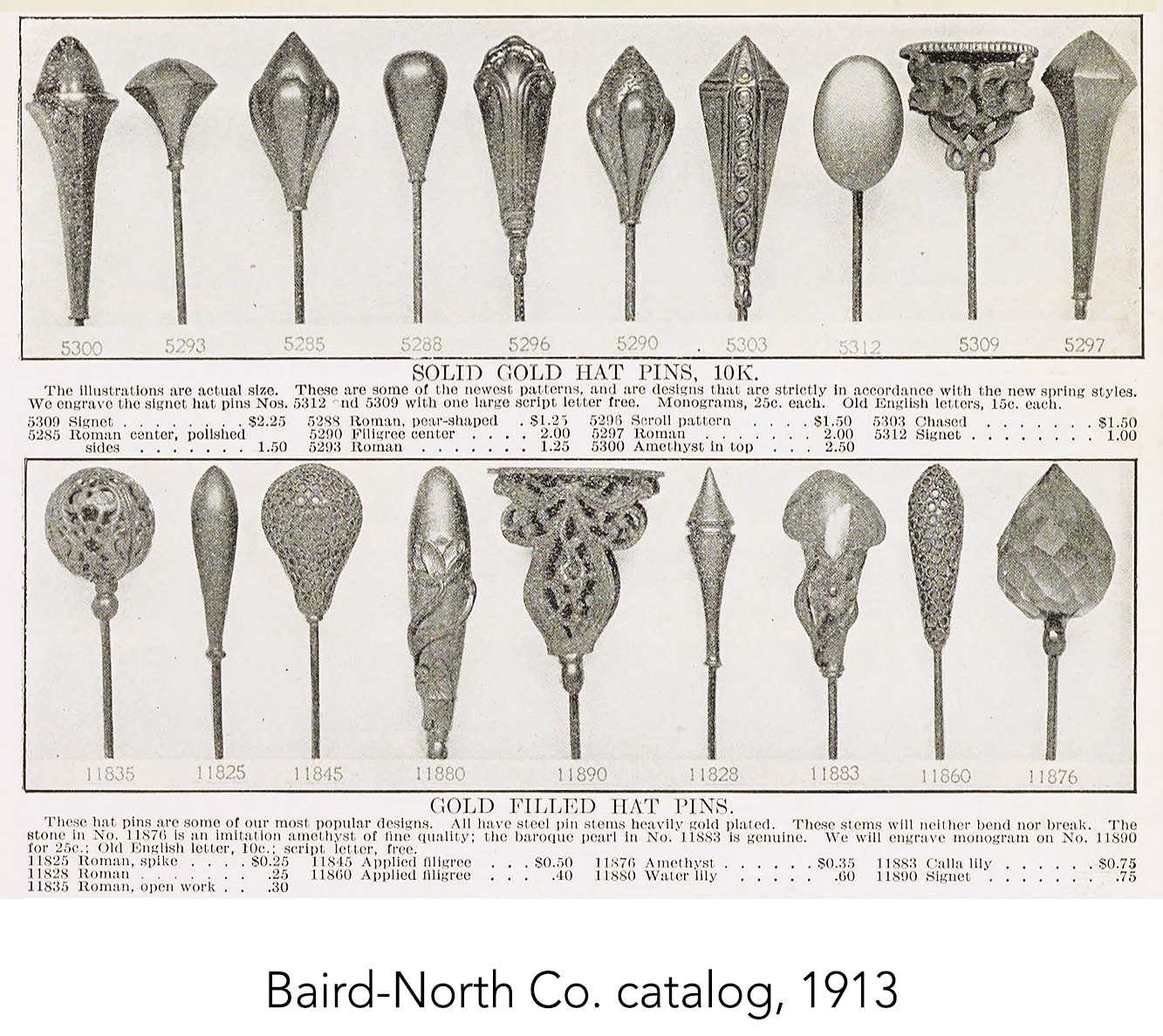

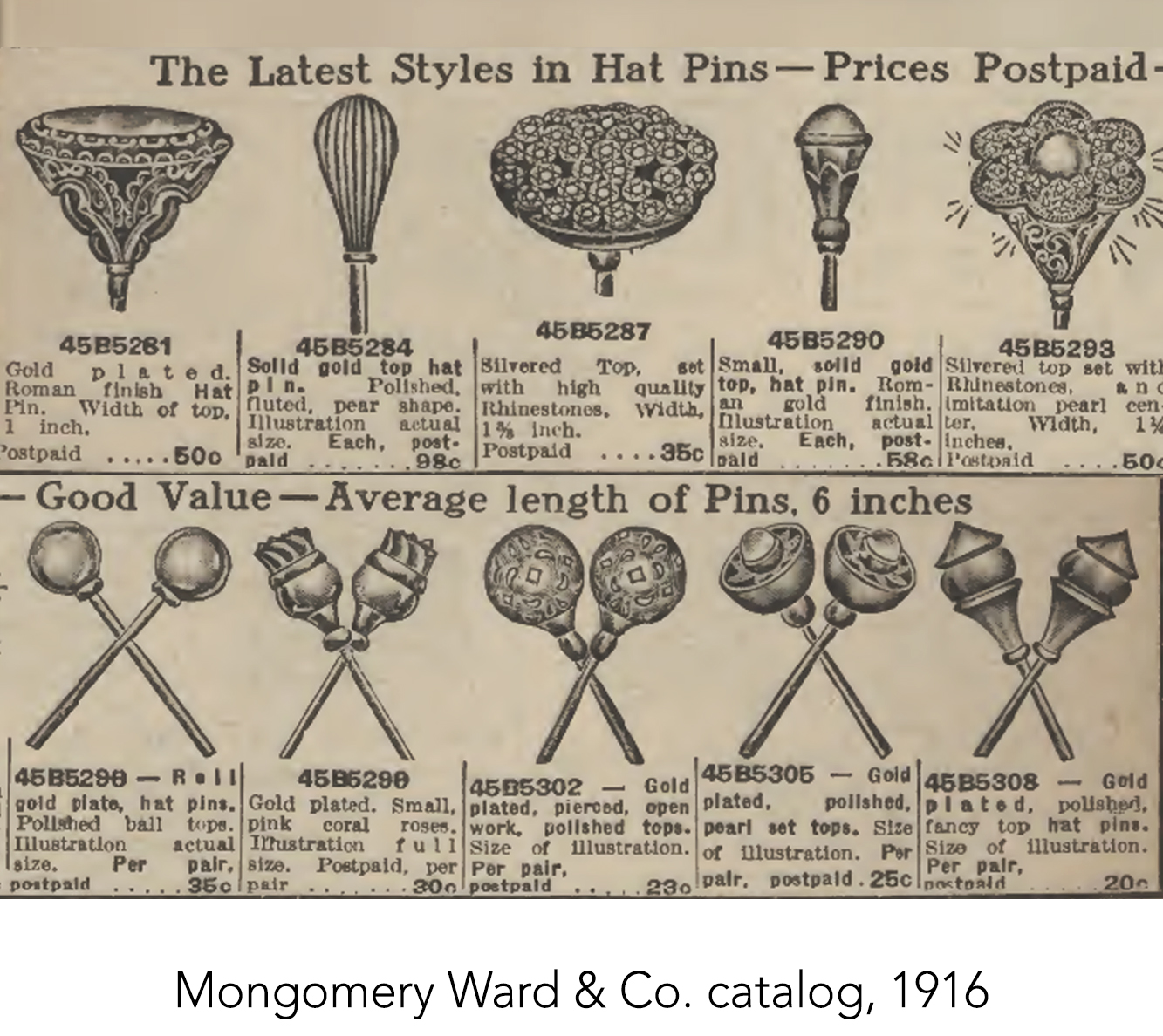

Throughout history, and as far back as the Middle Ages, women have sometimes used pins to secure their fashionable hats and other headpieces. But nothing compares to the hatpins used by women in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The decorative heads of these pins could be made of gold, silver, enamel, or porcelain, and occasionally included precious stones or paste, depending on what the wearer could afford. Sometimes homemade hatpin heads were made from fancy buttons or military metals that belonged to a loved one. They could also be made of natural elements like ivory, horns, or even roses, as you can see in the Daily Arizona Silver Belt (Globe, AZ – September 8, 1908). But it’s the straight part of the pin that could really catch your attention, with pin lengths on average from 6 to 12 inches, or even longer! Why were they so big? Because the hats themselves were bigger around the turn of the 20th century, with brims of the largest and most fashionable ones extending beyond a woman’s shoulders. To secure these charming chapeaus, women relied on one or sometimes multiple hatpins that would poke into the hat and the woman’s hair, and at times out the other side.

At Rosson House, we have three hatpins in our collection, and all three are on display upstairs in the sewing area, in a porcelain hatpin holder from that same period. The two gold hatpins are about 8 inches in length, and the black one is 6 ¾ inches.

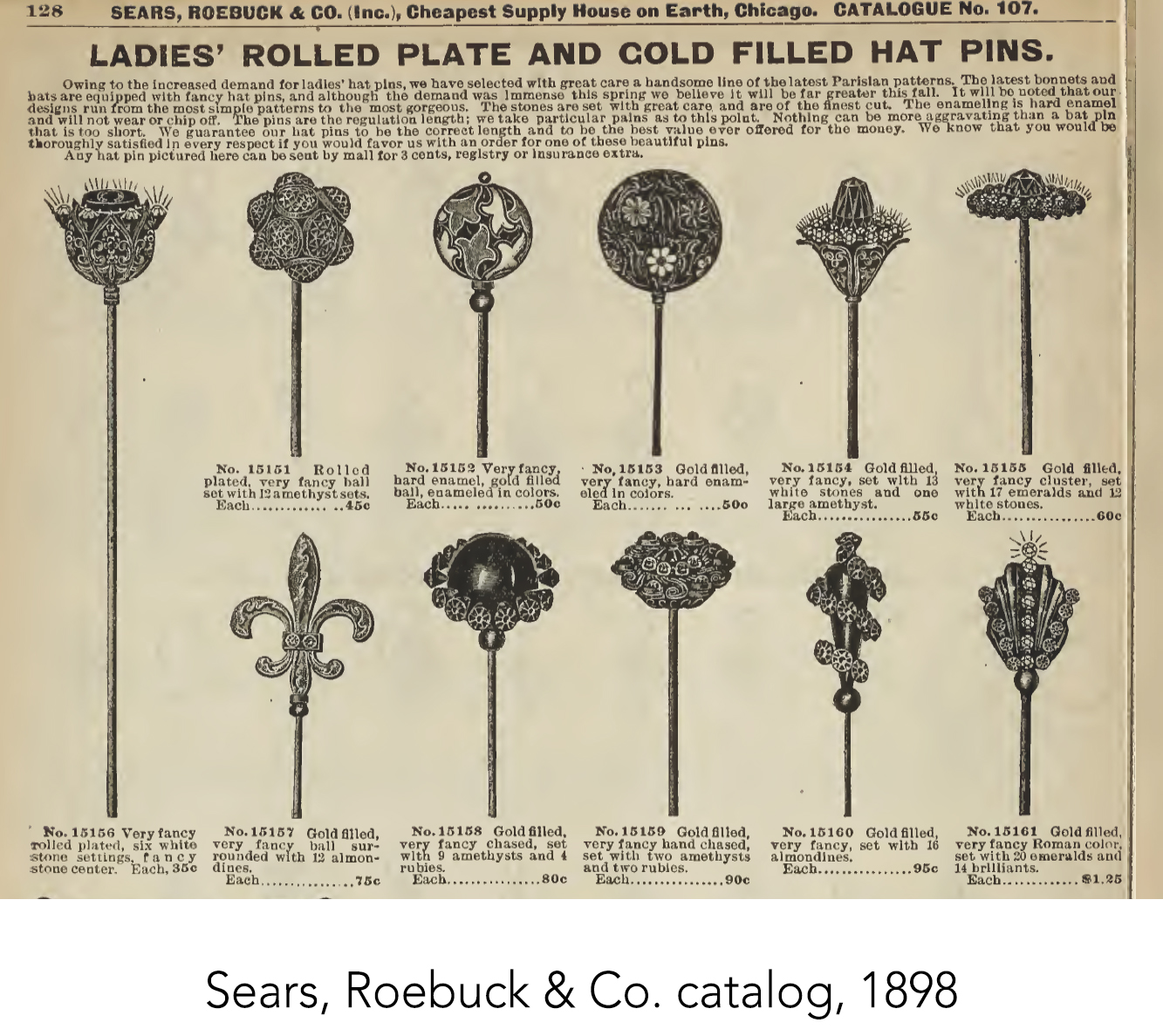

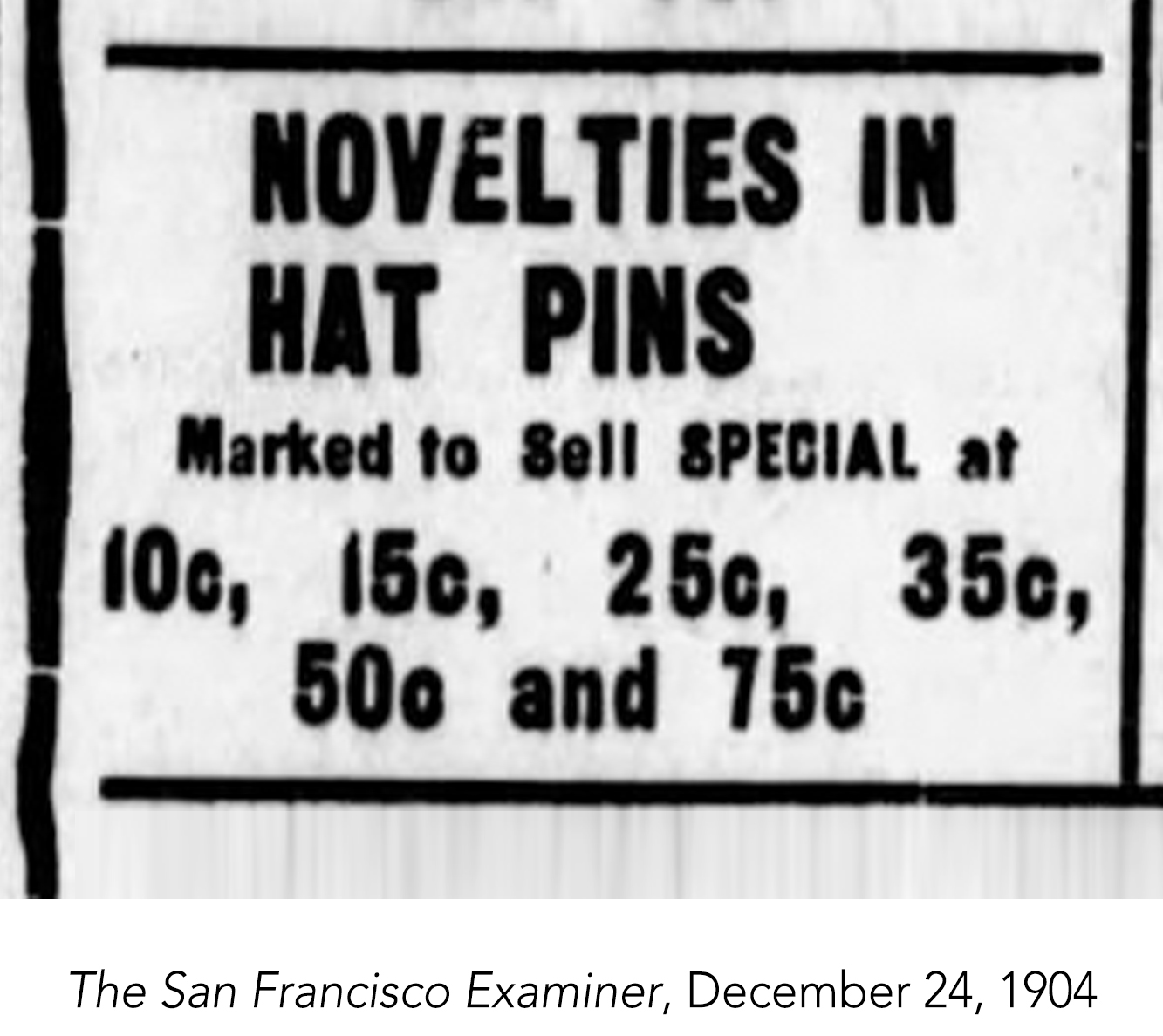

Hatpins were a popular enough accessory to be advertised in magazines and newspapers, sold in widely obtainable catalogs like Sears Roebuck & Co. and Montgomery Ward & Co., and also sold by upscale jewelers like Tiffany & Co and Cartier. Some social groups and societies would have hatpins engraved for their members, like this silver hatpin made for the Auckland Ladies Hockey Association in 1911 (which measures in at just over 10 inches). To store hatpins at home, women used porcelain or ceramic hatpin holders, like in the photo here of Rosson House hatpin collection.

Hatpins were a popular enough accessory to be advertised in magazines and newspapers, sold in widely obtainable catalogs like Sears Roebuck & Co. and Montgomery Ward & Co., and also sold by upscale jewelers like Tiffany & Co and Cartier. Some social groups and societies would have hatpins engraved for their members, like this silver hatpin made for the Auckland Ladies Hockey Association in 1911 (which measures in at just over 10 inches). To store hatpins at home, women used porcelain or ceramic hatpin holders, like in the photo here of Rosson House hatpin collection.

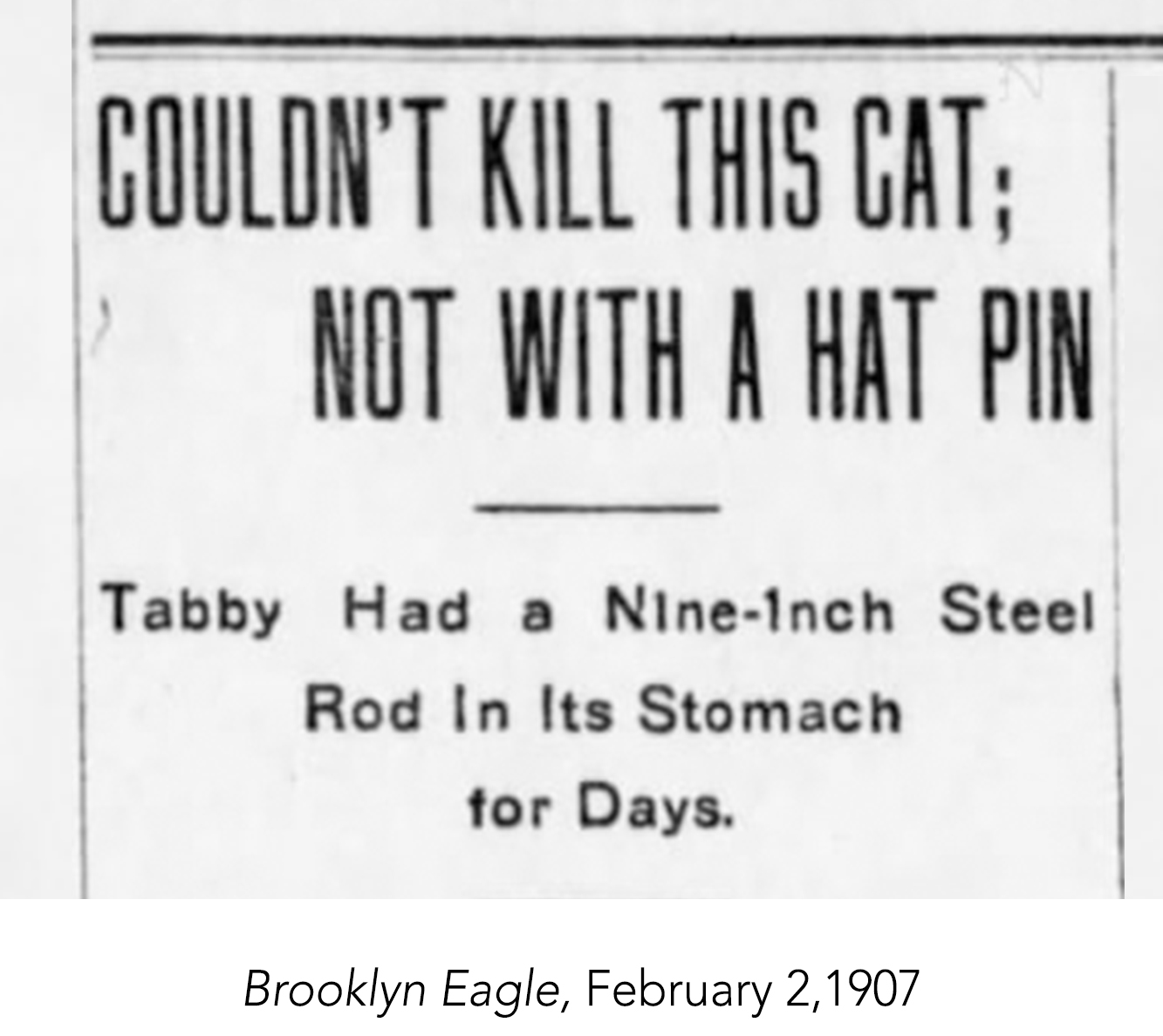

But as fashionable and practical as they were, hatpins could also be dangerous, even on accident. Scratches or minor pokes from a pin may not seem terribly hazardous to us, but before the development of antibiotics and vaccines, the danger of developing tetanus or an infection (i.e. – blood poisoning/sepsis) were high, and both could be fatal, even from minor cuts or abrasions. There were many newspaper accounts around the turn of the 20th century that told of accidental injuries to hatpin wearers and the people around them.

Eyes were unfortunately a common victim to hatpins worn in crowds. A Boise, ID, man was walking in a group of people when the woman in front of him stopped suddenly, and her protruding hatpin stabbed him in the eye. The attending doctor was hopeful the man’s eyesight could be saved (Evening Capital News, November 25, 1912). A teenager was accidentally stabbed in the eye by a hatpin while watching a baseball game in Vacaville, CA, and was taken to Sacramento to see a specialist because of the seriousness of the injury (The Sacramento Bee, October 14, 1911). During a train ride in Connecticut, a hatpin scratched the eye of a broker when a woman turned to speak to a friend. The Fulton County News reported that he might lose his eyesight because of the injury (August 17, 1911).

Crowded transportation was often where injuries initially took place. Howard Miller of Binghamton, NY, died of blood poisoning a few days after being scratched by a woman’s hatpin as he was riding next to her in an electric car. (Elmira Star-Gazette, February 16, 1907). Similarly, Captain Andrew England was scratched on his cheek by a hatpin while riding in a street car, developed an infection, and died three weeks later (The Patriot-News, February 17, 1911).

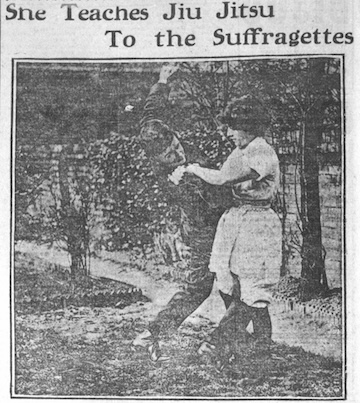

An image from an article on self-defense in the Fargo Forum newspaper, July 17 1909.

Being the person wearing a hatpin didn’t prevent a person from accidentally being injured by one. The San Francisco Call & Post (October 17, 1904) related a story about a woman who was accidentally hit in the head by a football, which drove her hatpin into her head, severing a blood vessel. A woman in Santa Fe, NM, reportedly developed lockjaw, a symptom of tetanus, after accidentally stabbing herself with a hatpin. (Santa Fe New Mexican, May 17, 1905).

-

Hollywood's Hatpin Homicide

“House of Silence” was a popular silent film made in 1918 about a woman who – spoiler alert! – defends herself from a masher by fatally stabbing him in the heart with a hatpin. It was advertised locally in the Tucson Citizen (July 21, 1918) and the Arizona Republic (January 3, 1919), as well as nationally in newspapers from Hawaii to Michigan.

An AFI summary of the film from IMDB:

“A young woman, disheveled and greatly distressed, stops criminologist Marcel Levington on the street and begs him to find a doctor for a man who is dying inside a nearby house of ill repute. Marcel and his friend, Dr. Rogers, enter the house and find the man, a prominent lawyer, dead, his heart pierced by a hatpin that the doctor recognizes as the one he recently gave his daughter Toinette. Rogers announces that the man has died of heart failure, returns home and demands an explanation from his daughter, who explains that she was lured into the house and attacked by the man. Realizing that Toinette killed the lawyer to defend her honor, Rogers and Marcel agree to protect her. Marcel retrieves Toinette’s pocketbook from the proprietor of the house, Mrs. Clifton, who had planned to blackmail the girl, and then returns to Toinette, with whom he has fallen in love.”

Like so many movies from the Silent Film Era, “House of Silence” is thought to be lost to history. Because they were recorded on celluloid film that is both flammable and susceptible to deterioration, the US Library of Congress has estimated that only 14% of all silent films ever made still exist. Learn more about the history of filmmaking from our August 2021 blog article, Moving Pictures.

Side Note: The Arizona Republic shows “House of Silence” playing at the Lamara Theater, formerly located in downtown Phoenix at 11 E. Washington St. The Lamara was opened by Captain Lawson and J. T. McNamara on January 22, 1913, next to the National Bank of Arizona. Operating next door to a successful bank may have been the theater’s downfall – the bank purchased the property and bought the lease on the building in 1919 so they could extend their presence along Washington. The Lamara closed for good in May 1920.

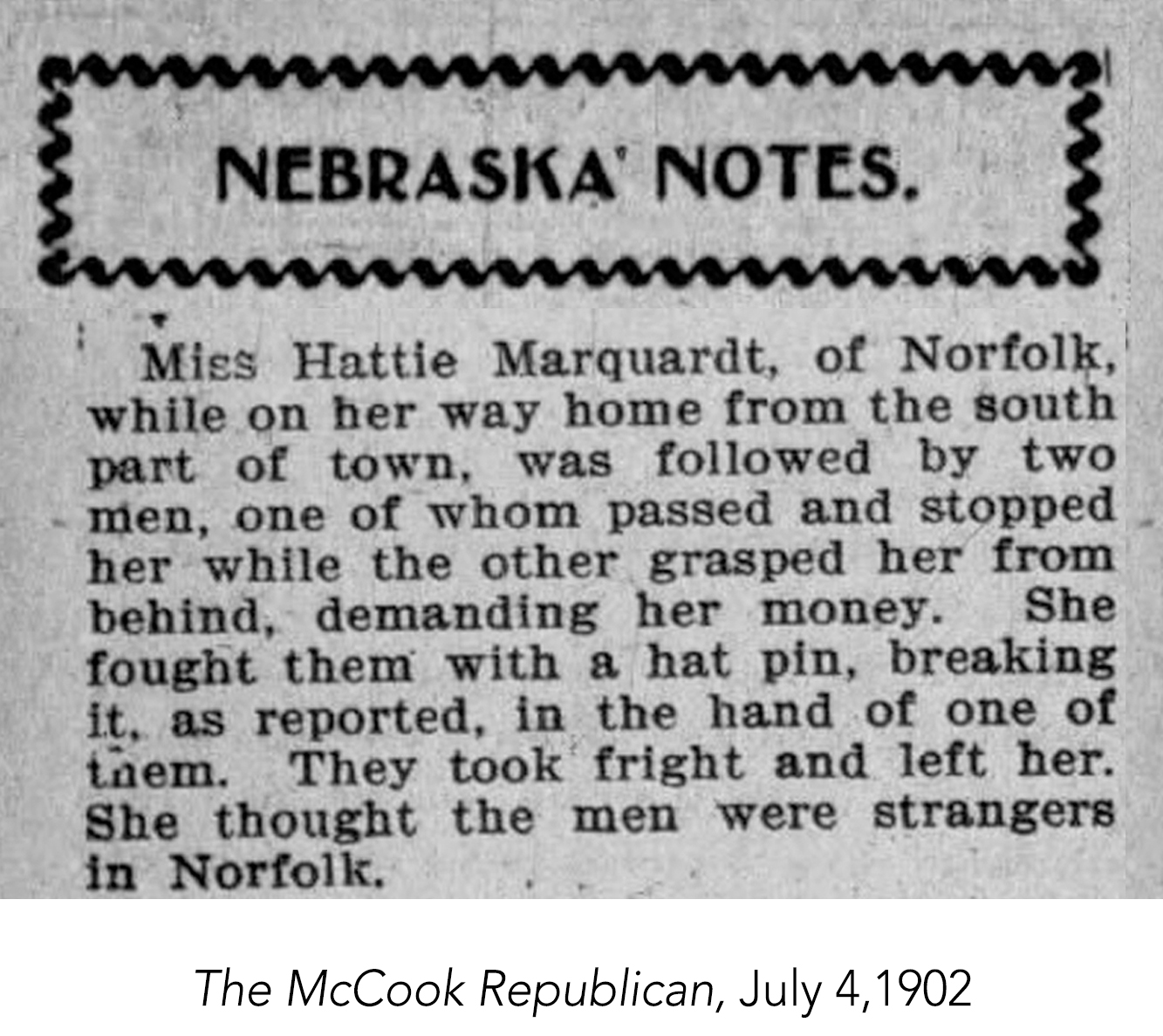

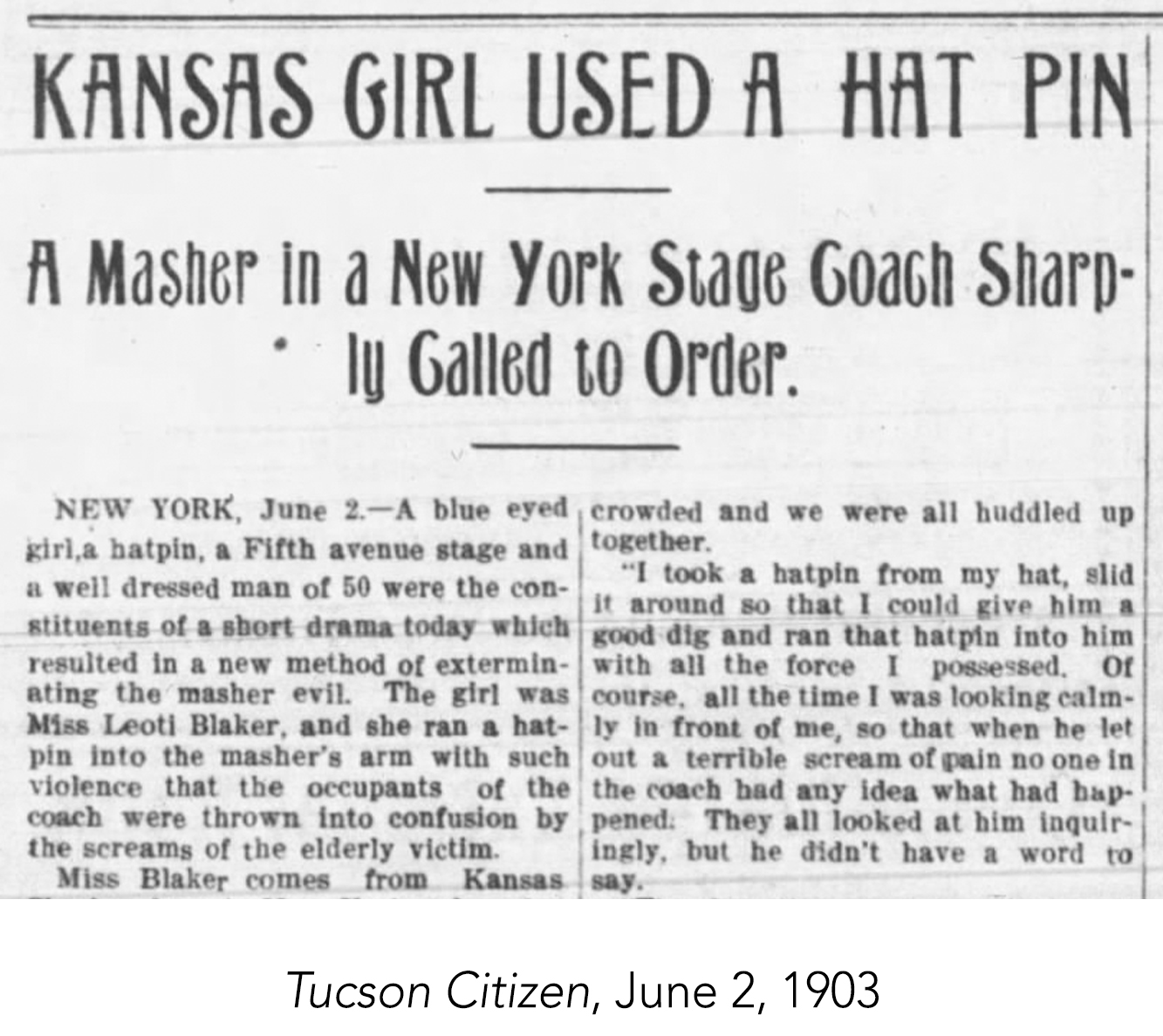

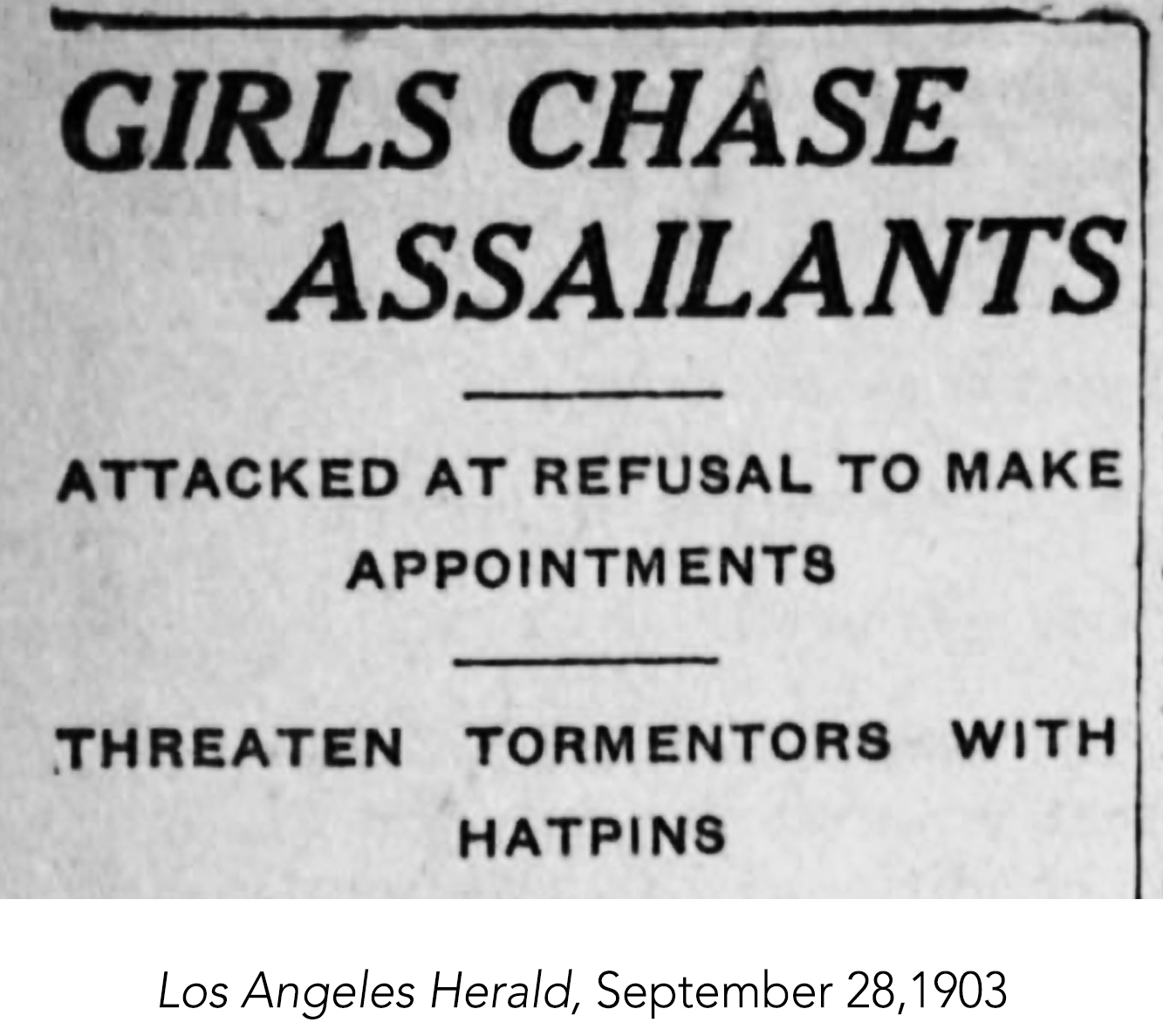

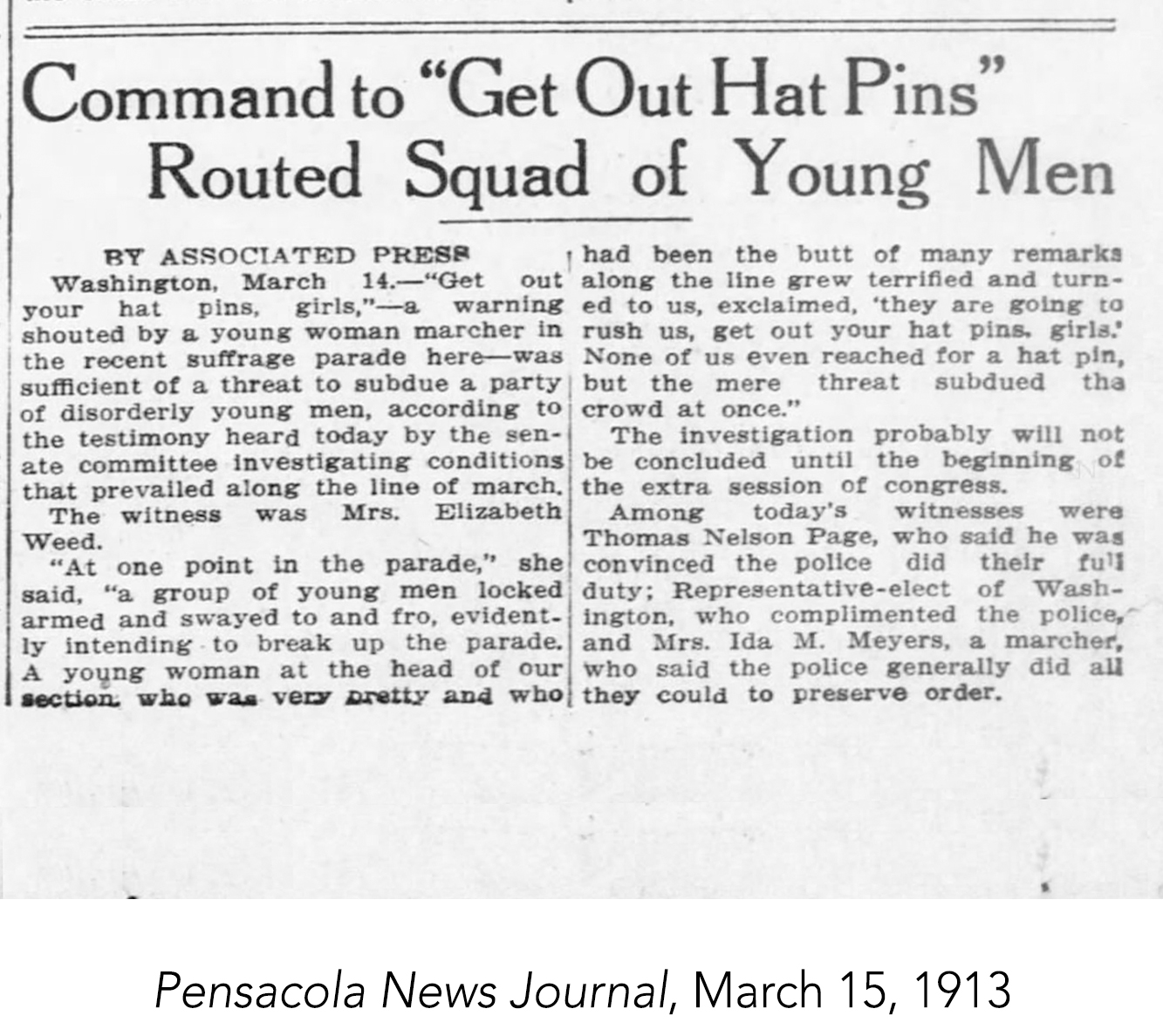

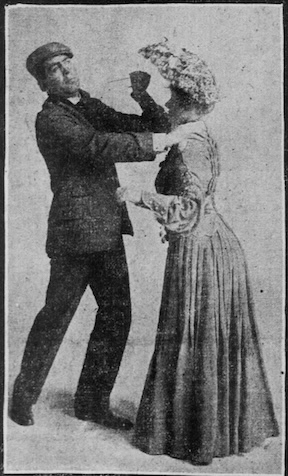

Equally as often, however, there are stories in turn-of-the-century newspapers about women stabbing people with hatpins on purpose. During this period, women increasingly found themselves in new places, either for travel or employment, without the accompaniment of male family members. This shift in social dynamics was accompanied by a rise in incidents of sexual harassment and assault, and left women to navigate these challenges on their own. Some turned to new self-defense measures like boxing and jujutsu, which were at the same time lauded as practical and vilified as “vulgar” and “indecent”. Others used everyday items as weapons to defend themselves, like umbrellas and parasols, riding whips, and even hatpins.

In a widely shared tale, a visitor to New York City stabbed an older “masher” (“masher” = a sexual harasser or assaulter) in the arm after he had pressed up against and put his arm around her while they were on the Fifth Avenue coach. She was reported as saying, “If New York women will tolerate mashing, Kansas girls will not.” The man screamed and jumped off the coach at the next corner (Carlisle Evening Herald, May 29, 1903).

In some newspaper accounts, women who used hatpins as weapons remained anonymous, as was the case reported in the Las Vegas Daily Optic (October 12, 1897), where a young man was stabbed with a hatpin and refused to reveal his assailant. The stabbing proved to be fatal.

From The San Francisco Call and Post (August 21, 1904) article titled, “How to Defend Yourself” aimed at teaching women self-defense.

At times, women were lauded for stabbing mashers with hatpins, like in the story above of the woman from Kansas, and other times they were held criminally liable. The Evening World (June 6, 1894) reported of a trial in which a woman was held on “a charge of felonious assault” for stabbing a man with a hatpin after he tried to kiss her. In The San Francisco Call (February 2, 1899), they reported a woman was wanted by the authorities for stabbing a man with a hatpin who she claimed had assaulted her 13 year old daughter.

Other stories of hatpin attacks include women who fought each other with hatpins, or who attacked people in general. The Weekly Journal-Miner from Prescott (January 22, 1913) reported that a woman who claimed to be a Pinal County teacher tried to stab a policeman with her hatpin while she was taken into custody in an attempt to ascertain her mental state. Some women even used hatpins as a part of criminal activity – a group of “female bandits” robbed a man of $150 and stabbed him with a hatpin when he resisted (The Times, October 5, 1899).

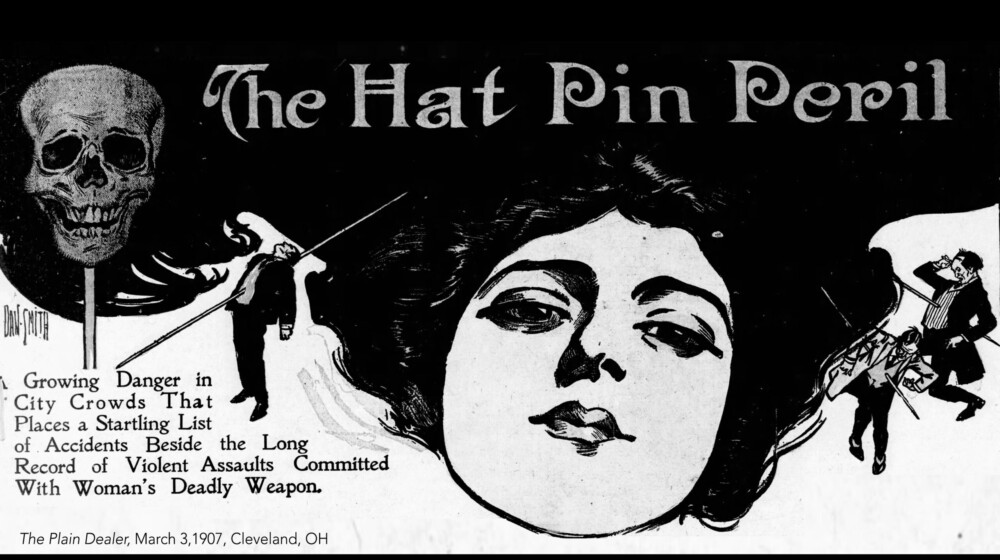

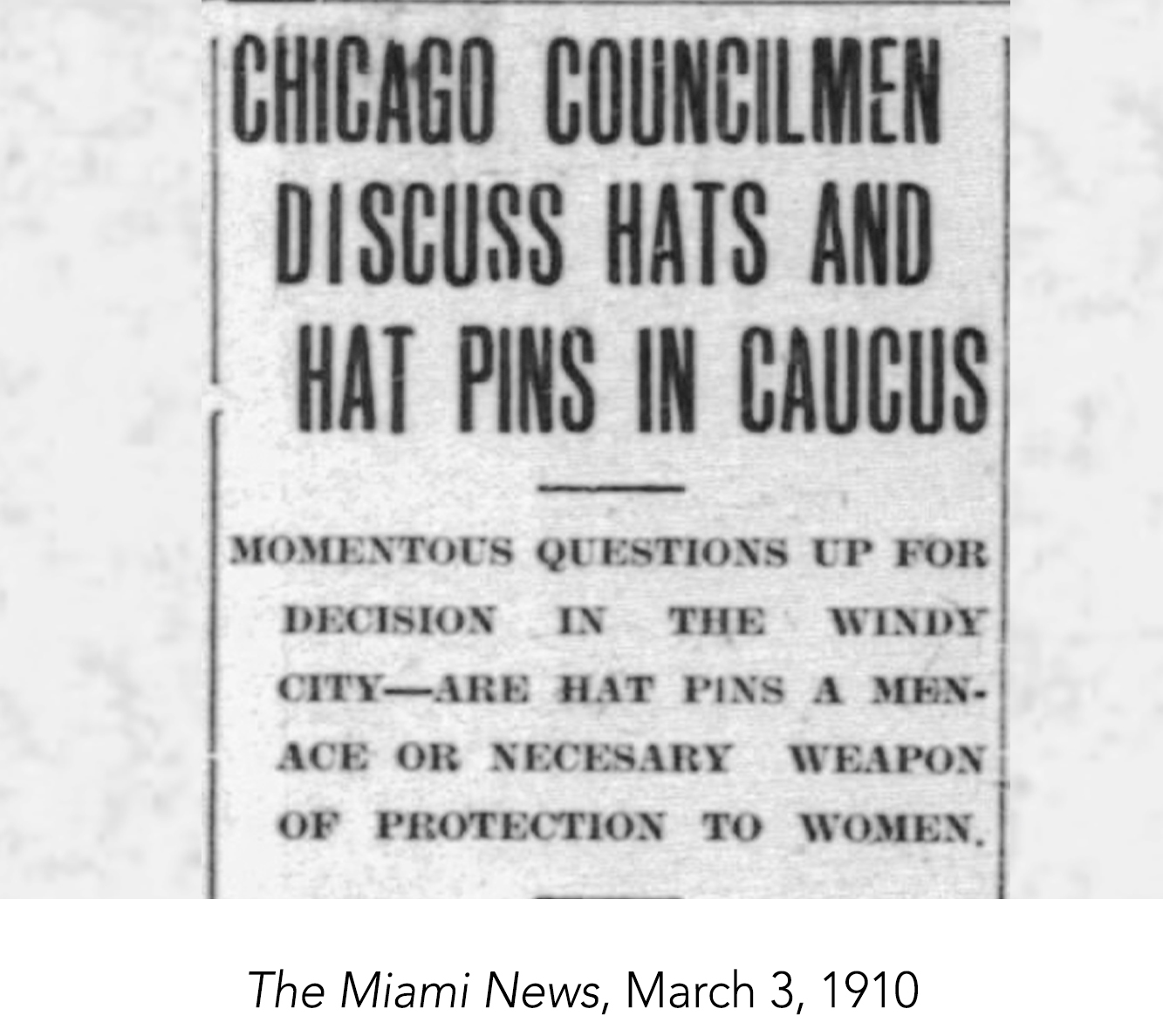

Despite violent acts like homicide being overwhelmingly perpetrated by men – statistics from the US Census Bureau show that women committed 20-27% of all homicides between 1900 and 1920 – newspapers fueled the notion of women using hatpins as dangerous weapons, as highlighted in the article that accompanied the image at the top of the page, and lawmakers decided there had to be something done about women and their hatpins. Citing accidental injury as their primary concern, several American cities – including Seattle, New Orleans, Milwaukee, Brooklyn, and Colorado Springs – passed ordinances to restrict the length of women’s hatpins. A Nevada law went into effect on January 1, 1912, making it a misdemeanor for a person to wear in public a hat pin protruding over half an inch beyond the crown of a hat, unless the point of the pin was covered. Offenders could be fined up to $500 and sentenced to 6 months in jail.

As hat fashions changed, and hats became sleeker and more form-fitting, the need for hatpins became less necessary, though they didn’t completely disappear. Our Visitor Engagement Director, Sarah Matchette, has a favorite story about her dad, James Matchette, and a hatpin:

“My father was a security guard at a California department store in the 1970s. Once he was alerted to an older woman in the store who might be stealing, so he went up to talk to her. When my dad went to turn away from her, she pulled a hatpin out of her hair and stabbed him from behind, before making a run for it. According to my dad, she nicked his tailbone, which is why he was able to predict when it was going to rain for the rest of his life.”

Hatpins were mentioned in newspapers from the 1970s onward mainly as antiques, but again in articles as a way for women to protect themselves from assault. The author of an article in the Anaheim Bulletin (October 13, 1977) suggested women carry, among other things, hatpins to “stab a man in the neck and run for safety”.

You can see more period headlines, catalog pages, and ads for hatpins below. Hint – By right-clicking the image and opening it in another tab, you’ll be able to see the text more clearly.

Information for this article was found in Beware the Masher: Sexual Harassment in American Public Places, 1880-1930, by Kerry Segrave (2014); The Hatpin Menace: American Women Armed and Fashionable, 1887-1920, by Kerry Segrave (2016); Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970, United States Census Bureau (bicentennial edition, 1975).

Information was also found online through the Library of Congress Chronicling America and Newspapers.com digital newspaper archives, as well as from the following sources: The American Hatpin Society – A Brief History of Hatpins; Vintage Fashion Guild – History of Hats for Women; Smithsonian Magazine – “The Hatpin Peril” Terrorized Men Who Couldn’t Handle the 20th-Century Woman, and American Women in the 1900s Called Street Harassers ‘Mashers’…; The Desert Sun – Antiques: Hatpins – the elegance, the utility, the danger; The Journal of the Gilded Age & Progressive Era, Vol. 13, No. 4 (Oct 2014), pp. 470-499 – …Women and the Practice of Self-Defense, 1890-1920 (via JSTOR); Washington Square Magazine (San Jose State University) – Her Own Hero: The History of Women’s Self-Defense; Smithsonian Institution – The Antibody Initiative: Battling Tetanus.

Archive

-

2025

-

January (1)

-

-

2024

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-