On the Air

For a printable version of this article, please click here.

Did you know…

While doing research for our May blog article, we discovered that the 1930 Census asked if households owned a radio (our favorite census question to date!). At Heritage Square, the Gammel family (Rosson House) is recorded as having a radio set, along with Marguerite Haustgen (Stevens-Haustgen House) and the people who were renting the Stevens House from her. About 40% of the population was recorded as having a radio set in the census. The cheaper of the two shown here, sold in the 1930 Sears Roebuck fall catalog, cost $21.50 (approximately $376 today), so still a sizable investment, particularly during the Great Depression.

While doing research for our May blog article, we discovered that the 1930 Census asked if households owned a radio (our favorite census question to date!). At Heritage Square, the Gammel family (Rosson House) is recorded as having a radio set, along with Marguerite Haustgen (Stevens-Haustgen House) and the people who were renting the Stevens House from her. About 40% of the population was recorded as having a radio set in the census. The cheaper of the two shown here, sold in the 1930 Sears Roebuck fall catalog, cost $21.50 (approximately $376 today), so still a sizable investment, particularly during the Great Depression.

The Marconi radio (patented in 1899, but possibly based on Tesla’s design) was the first telegraph that could operate wirelessly, sending transmissions in Morse code across bodies of water to other countries and to/from ships at sea via sound waves. Though the first sound broadcast was in 1906, it wasn’t until 1920 that the first commercial radio newscast took place, from station 8MK in Detroit, communicating live local election results as they happened instead of people having to rely on reading the news in the paper the next day. They were followed later that fall by a station in Wilkinsburg, PA (KDKA), who also broadcast the results of an election – this time the 1920 presidential election (spoiler alert – Harding won). Less than a year later, KDKA would broadcast play-by-play of the first baseball game (the Pirates came back from behind to beat the Phillies 8 to 5) and the first football game (West Virginia University lost to the University of Pittsburgh, 21 to 13).

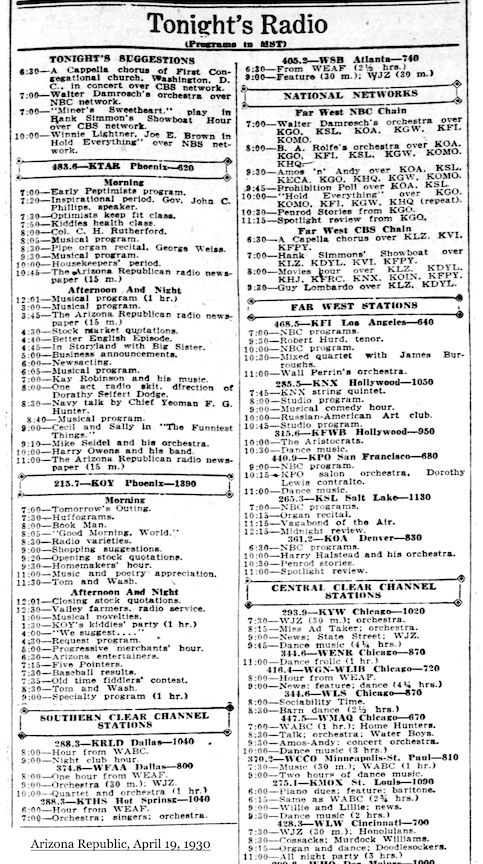

One hundred years ago last month (June 21, 1922), Phoenix’s first radio station (KFAD) went on the air. Their broadcast signal was 100 watts (compared with modern radio signals broadcast at 50,000 to 100,000 watts), and programming included opera, classical music, lists of stolen cars with their description and license numbers, as well as mining news (market reports, price changes, etc), and live performances from the Arizona School of Music. That fall, they brought their equipment to the State Fair to give a radio concert where a loud speaker was set up so that the music could be heard “in every section of the grandstand.” That same year, public buses in Oakland, CA were equipped with radios for riders to enjoy, and a hotel in San Francisco installed radios in their restaurant for diners to listen to while they ate.

It didn’t take long for radio programs to become more scripted and commercialized. The first radio ad was broadcast on August 28, 1922 at station WEAF (New York), owned at that time by AT&T. By the 1930s, ads were so prevalent many programs were created solely to promote sponsors’ products!

-

This Means War!

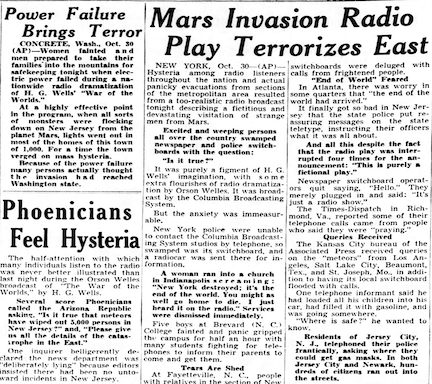

‘Twas the night before Halloween in 1938, when many Americans had the tradition of relaxing in their homes and listening to their radios after a big Sunday dinner. This time, though, when they turned on their sets they heard, to their horror, that Martians had crashed into a field in New Jersey and swarmed the crash site, firing a heat ray that killed 7,000 members of the National Guard. It was terrible! Some people began to panic, particularly after learning that more cylinders were crashing across the nation. And who can blame them! They called police stations, newspaper offices, radio stations, fire stations – anyone who might have answers about what was going on. But what was actually happening was…Nothing. There were no Martians, no heat rays, no cylinders, nothing. The National Guard was just fine. There was no attack whatsoever. It was all a work of fiction, based on a book by HG Wells written four decades prior, and turned into a radio program by Orson Welles and his team – writer Howard Koch, producer John Houseman, and veteran radio actor Paul Stewart.

‘Twas the night before Halloween in 1938, when many Americans had the tradition of relaxing in their homes and listening to their radios after a big Sunday dinner. This time, though, when they turned on their sets they heard, to their horror, that Martians had crashed into a field in New Jersey and swarmed the crash site, firing a heat ray that killed 7,000 members of the National Guard. It was terrible! Some people began to panic, particularly after learning that more cylinders were crashing across the nation. And who can blame them! They called police stations, newspaper offices, radio stations, fire stations – anyone who might have answers about what was going on. But what was actually happening was…Nothing. There were no Martians, no heat rays, no cylinders, nothing. The National Guard was just fine. There was no attack whatsoever. It was all a work of fiction, based on a book by HG Wells written four decades prior, and turned into a radio program by Orson Welles and his team – writer Howard Koch, producer John Houseman, and veteran radio actor Paul Stewart.There’s no definitive answer as to how many people were fooled by the broadcast, but the FCC (Federal Communications Commission) did field many complaints about the broadcast, which they investigated to see if any laws were broken (there weren’t). Even as far away as Phoenix, the newspaper reported people calling in to learn about the “catastrophe in the East.”

Was the program that good? You be the judge! You can listen to the entire War of the Worlds radio broadcast from the Internet Archive.

Music of all kinds – jazz, blues, country (the first Grand Ol’ Opry broadcast was on November 28, 1925), classical music, opera, show tunes, and more – were popular radio content in the Golden Days of Radio (before, as they say, video killed the radio star). So were lectures, readings (some stations even did a children’s bedtime story each evening), news updates and politics, household hints like The Wife Saver (1929-43), variety programs like The Jack Benny Program (1932-55), crime stories like The Shadow (1937-54) and Perry Mason (1943-55), and sports. Unfortunately, many of these shows, like the popular Amos ‘n’ Andy show and serialized Westerns like The Lone Ranger, were based on racist African American and Native American stereotypes, which prevailed in movies and later in TV, too. Chicago’s WSBC finally broadcast the first radio show in the US with an all-Black cast in 1929 with their “All-Negro Hour,” a variety show devoted specifically to Black performers that sought to stop the spread of negative racist stereotypes. Its host, Jack L. Cooper, continued to create radio programming for WSBC centered on the Black experience, including Search for Missing Persons (1938), a show that reunited African American migrants from the South with lost friends and relatives. In 1948 the first Black-owned radio station (WERD) began broadcasting in Atlanta, GA. It would take over 20 years for the first Native American-owned and operated radio station to open in Alaska (KYUK-AM).

Music of all kinds – jazz, blues, country (the first Grand Ol’ Opry broadcast was on November 28, 1925), classical music, opera, show tunes, and more – were popular radio content in the Golden Days of Radio (before, as they say, video killed the radio star). So were lectures, readings (some stations even did a children’s bedtime story each evening), news updates and politics, household hints like The Wife Saver (1929-43), variety programs like The Jack Benny Program (1932-55), crime stories like The Shadow (1937-54) and Perry Mason (1943-55), and sports. Unfortunately, many of these shows, like the popular Amos ‘n’ Andy show and serialized Westerns like The Lone Ranger, were based on racist African American and Native American stereotypes, which prevailed in movies and later in TV, too. Chicago’s WSBC finally broadcast the first radio show in the US with an all-Black cast in 1929 with their “All-Negro Hour,” a variety show devoted specifically to Black performers that sought to stop the spread of negative racist stereotypes. Its host, Jack L. Cooper, continued to create radio programming for WSBC centered on the Black experience, including Search for Missing Persons (1938), a show that reunited African American migrants from the South with lost friends and relatives. In 1948 the first Black-owned radio station (WERD) began broadcasting in Atlanta, GA. It would take over 20 years for the first Native American-owned and operated radio station to open in Alaska (KYUK-AM).

Despite the Great Depression, radio ownership grew in the 1930s. The 1930 census recorded radio sets in about 12 million households. By the 1940, that number had more than doubled, with 28 US million households owning radios. President Roosevelt’s Fireside chats, which he began just after his first inauguration in 1933, would carry over from an economic crisis to a world war. During the war, radios were essential to people on the homefront, as they waited for updates about the war and their loved ones who were serving overseas. After the war, however, production of appliances soared, including the manufacture of the televisions (developed in the 1920s, but put on hold during the war). Though radios were everywhere you could imagine – in planes, trains, and automobiles, in homes and buildings all over – by 1955 about half the American population had TVs, and radio programming was being replaced with television programming. Some radio shows would successfully bridge that gap, including The Adventures of Superman (moved to TV in 1952), Dragnet (moved to TV in 1951, but continued on the radio as well until 1957), and I Love Lucy (known on the radio as My Favorite Husband; moved to TV with the new name in 1951). Today, the vast majority of American households have multiple televisions in their home instead of just one. Though much of our entertainment comes in video form these days, there are still over 15,000 radio stations in the US, with approximately 88 of them in the Phoenix listening area. And streaming services give local radio stations an even wider range.

Learn more about old radios from the Vintage Radio and Communications Museum of Connecticut. Explore the origins of Spanish-language radio here in the US from the National Museum of American History. Discover the Golden Age of Black radio from the Archives of African American Music & Culture.

Information for this article was found in the Arizona Republic (June-December 1922); PBS; the FCC; the Hancock Historical Museum; the Nobel Prize website; the Archives of African American Music & Culture; the Southwest Museum of Engineering, Communications and Computation; History Hub; Smithsonian Magazine; the Digital Public Library of America; White House History; the Baseball Hall of Fame; History; MeTV; Statista; and Nielsen.

Archive

-

2025

-

January (1)

-

-

2024

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-