Moving Pictures

Did you know…

The Lumière brothers’ cinématographe.

The first known motion picture was made before Rosson House was built! Recorded in 1888 by Louis Le Prince, Roundhay Garden Scene is about 12 seconds of just what it sounds like – people walking around a garden. Though that seems very basic and kind of boring to us now, at that time it was an incredible scientific breakthrough. Up until that point, “movement picture” devices – like the thaumatrope (c1825) and the zoetrope (c1833), along with dozens of others – had only been able to give the illusion of movement. Many of these inventions, including William Dickson and Thomas Edison’s kinetoscope (which used the new roll film developed by George Eastman), were marketed as toys or novelties that could be enjoyed individually, but not by a group of people together like movies today are.

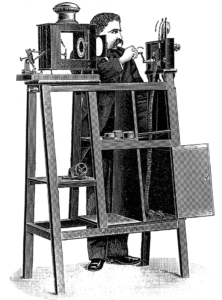

Inspired by the kinetoscope, Auguste and Louis Lumière created the cinématographe – the world’s first motion picture camera and projector that could show films to multiple people at once. They unveiled their invention to the public on December 28, 1895 at the Grand Café in Paris, with a film they recorded of workers leaving their factory. Like Roundhay Garden Scene, this and many other early films were short, less than a minute long – and depicted common, everyday scenes. What sparked people’s interest in these films, at least to begin with, was the uniqueness of their very existence.

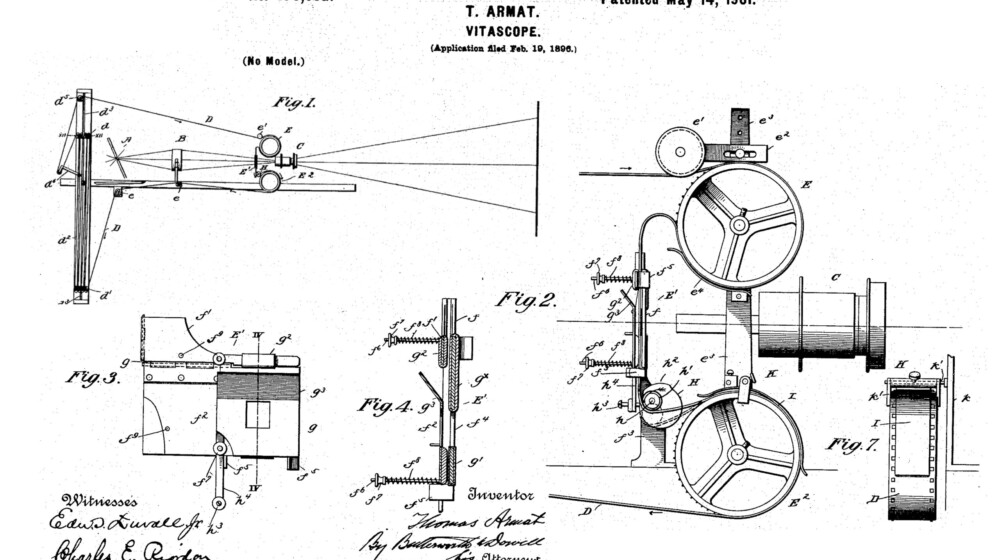

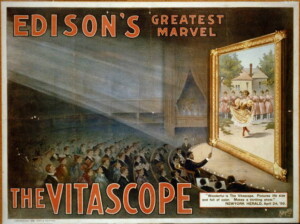

More movie cameras and projectors were invented (like Thomas Armet’s vitaphone – shown at top – which would eventually be bought out by Thomas Edison), and the popularity of these novelty films grew. Traveling entrepreneurs toured the country with a projector and reels of film, to set up shop in big and small towns alike for a couple of days, showing their movies in theaters, opera houses, or even tents, charging up to 75 cents for admission to see the series of short films they brought with them. The movies would be shown in between live vaudeville acts and music performances, and featured travel in far off places along with sensational events like President McKinley’s assassination and funeral, boxing prize fights, Spanish bull fighting (marketing for these included mentioning multiple deaths of animals and people!), the San Francisco earthquake and subsequent fire, and recreations of the Spanish-American War. Movie makers also began creating fictional films as well, with amazing adventures like A Trip to the Moon by George Méliès (c1902) and The Great Train Robbery by Edwin S. Porter (c1903).

Towns soon saw the advantage of having their own “electric” (movie) theaters. The first permanent building in the US dedicated solely to showing motion pictures, Tally’s Electric Theatre, opened to the public in Los Angeles on April 16, 1902. It could seat 250 people, and charged 10 cents for admission. The first Nickelodeon (named using the cost of admission plus the ancient Greek word for theater – “odeon”) opened in Pittsburgh, PA on June 19, 1905. Set up in a storefront with a cinématographe projector, a framed screen, a piano, and about a hundred chairs, they could show movies all day long and it cost just a nickel’s admission. These kinds of theaters would prove to be wildly popular, and in just two years over 8,000 Nickelodeons would pop up all over the country. The silent shows with their “mood” music played in the background were broadly appealing because of their affordability, and also because of their lack of a language barrier – 1.3 million immigrants came to the US in 1907 (a record number at that time, and a number that wasn’t reached again until the 1990s).

Towns soon saw the advantage of having their own “electric” (movie) theaters. The first permanent building in the US dedicated solely to showing motion pictures, Tally’s Electric Theatre, opened to the public in Los Angeles on April 16, 1902. It could seat 250 people, and charged 10 cents for admission. The first Nickelodeon (named using the cost of admission plus the ancient Greek word for theater – “odeon”) opened in Pittsburgh, PA on June 19, 1905. Set up in a storefront with a cinématographe projector, a framed screen, a piano, and about a hundred chairs, they could show movies all day long and it cost just a nickel’s admission. These kinds of theaters would prove to be wildly popular, and in just two years over 8,000 Nickelodeons would pop up all over the country. The silent shows with their “mood” music played in the background were broadly appealing because of their affordability, and also because of their lack of a language barrier – 1.3 million immigrants came to the US in 1907 (a record number at that time, and a number that wasn’t reached again until the 1990s).

-

Learn More: Reel-y Racist

One of the most popular films across the country in 1915, including here in Arizona, was DW Griffith’s epic, Birth of a Nation. Though it was innovative for its scale – running at 3 hours, it was the longest movie made to that date – its legacy is fully eclipsed by its overwhelmingly racist content. The movie is based on the book The Clansman by Thomas Dixon Jr. (1905), and told a story that included the myth of enslaved people being happy with their captivity, portrayed people of color as criminals and savages, and cast the KKK as saviors of the nation. As sickening as it sounds, white Americans flocked to see the movie, and it was even screened by the president at the White House. Though the NAACP and others (including the Arizona Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs) denounced it and asked for the movie’s removal from theaters, it would become a box-office hit, earning an estimated $18 million in the first few years after its release, and reinvigorating the white supremacist movement in the US. Prior to its release, a play based on the book toured the country, and was presented at the Elks’ Theater here in Phoenix on December 8, 1908 (promoted by the Arizona Republican newspaper at that time as being on its, “4th Record Breaking Tour”).

In answer to this virulent racism, black movie maker Oscar Micheaux made Within Our Gates (1920), a film whose story would tell the unvarnished truth about racism and lynching in the American South, accurately depicting innocent black families falling victim to violent white mobs, and black women as targets of sexual assault from these same culprits. Where Birth of a Nation was lauded, Within Our Gates was not – some cities banned or censored it over “fears of racial unrest.” Though Micheaux would go on to make over 40 movies in his career, his work is not well known. Hollywood blocked people of color from the movie industry at all levels, and purposefully used white people in blackface to represent people of color on screen. When they did hire people of other races and ethnicities as actors, they did so for parts that were less central, underpaid, and stereotypical, depicting them as less intelligent, as predators and criminals, and as less than human. Things have gotten better with time with representation in movies and on TV, but African Americans, Latinos, Middle Easterners, Asian Americans, and Native Americans are still underrepresented in many film categories, and those with leads who were people of color or women were more likely to have smaller budgets than those with white and male leads.

-

Learn More: Perilous Pictures

George Eastman of the Eastman Kodak company invented the first roll film in 1885. It was made of a coated paper, and is the film Louis Le Prince used to record his moving picture in 1888. The film wasn’t as durable as he liked, so Eastman continued experimenting and in 1888, created celluloid/nitrate film. At first glance, it was a miracle product, used to create not only film but also more affordable jewelry, brush handles, hair combs, eyeglass frames, billiard balls, toys, piano keys, dice, and shirt collars and cuffs. There was one little problem items made of celluloid had, though – flammability. Items made of nitrocellulose have a rate of combustion that is 15 times that of wood. When subjected to heat or shock it can randomly explode or self-combust. When it does catch on fire, it contains enough oxygen in itself to allow it to continue burning without exposure to outside air (including when it’s immersed in water!), and it also emits toxic and flammable gases. Sounds like a great thing to have in a crowded movie theater, right??

Moving picture houses would take steps to prevent fires within their walls, relegating film and projectors to booths separate from movie audiences. Film was kept in iron “fire proof” boxes, and projection booths were lined with asbestos (another incredibly safe invention!) and equipped with safety shutters to prevent fires from spreading. Unfortunately, that did not stop fires from happening. On June 28, 1907, a blown fuse ignited a fire in the film being shown at the Alexander Theater in Globe, AZ, and the owner, J.M. Trimble, was badly burned. The same happened in Peoria in 1909, when projectionist Walter Woodrow was severely burned, and manager William Robinson was killed after an explosion in the Nickelodeon there. The towns would impose ordinances for movie theaters – requiring them to not sell more tickets than the number of seats available and not allowing standing room at the back of the theaters, amongst others. But a 1936 trade journal estimated that every 18 days an operator of a film projector died, which they attributed in part to the dangers of working with celluloid film. Moviemakers continued to use celluloid film even though the Eastman Kodak company invented acetate “Safety Film” in 1909, touting the sharper images and cheaper price tag nitrate based film offered. Kodak stopped making celluloid film altogether in 1951, forcing them to use safer products.

Movies and still photography negatives made from cellulose nitrate can still be dangerous. Inadequate ventilation in movie storage facilities caused fires to break out in the vaults of both 20th Century Fox (1937) and Metro-Goldwyn Mayer (1967), resulting in the loss of many silent films and early sound films. Because they were recorded on nitrate film that is both flammable and susceptible to deterioration, the US Library of Congress has estimated that only 14% of all silent films ever made still exist. Find out more about the safe storage of celluloid film from the American Museum of Natural History.

We can find evidence of films being shown in Arizona around that time from traveling companies like the Edna Page Comedy Co. (Phoenix, Arizona Republican, February 25, 1898), the Beaty Bros. (Phoenix, Arizona Republican, January 19, 1903), and the International Bioscope Co. (Flagstaff, Coconino Sun, February 4, 1905).  But even smaller towns were arranging to have their own permanent theaters – the residents of Globe were building a “moving picture house” in February 1907 (with planned admission at either 10 or 15 cents), and those of Douglas prepared to open one in their old post office building the following year. Phoenix even opened an outdoor movie theater in 1908, in the lot next to the alley on 1st Street, between Washington and Adams. It was close to the owners’ indoor theater, which they said would be used “on cool nights and during the daytime.”

But even smaller towns were arranging to have their own permanent theaters – the residents of Globe were building a “moving picture house” in February 1907 (with planned admission at either 10 or 15 cents), and those of Douglas prepared to open one in their old post office building the following year. Phoenix even opened an outdoor movie theater in 1908, in the lot next to the alley on 1st Street, between Washington and Adams. It was close to the owners’ indoor theater, which they said would be used “on cool nights and during the daytime.”

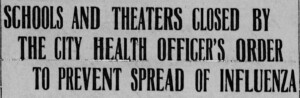

World War I and the Great Depression would only serve to increase the popularity of motion pictures, as people came together to support the war effort for the first, and as an escape from reality for both. Just one thing would come close to harming the fast-growing movie industry in those years – the 1918 influenza outbreak. As the disease swept through the country, cities and towns closed schools, churches, and movie theaters because of the threat of spreading the virus (sound familiar??). On October 9, 1918, the National Association of Motion Picture Industries announced an embargo on releasing new motion pictures by October 15th, due to the influenza epidemic. Over half of production was halted, and theaters remained closed in Phoenix for about nine weeks (October through early December). They reopened in time for the holidays, and then closed again in early January as cases spiked. Most theaters and production companies that hadn’t closed permanently reopened by spring 1919. The Hollywood studio system would emerge from the rubble, as big studios would buy out their competitors, and purchase and control movie theaters (a practice prohibited by the Supreme Court in 1948 due to anti-trust laws), centralizing power, money, and influence.

This blog article by no means covers all of cinematic history. Learn more here:

- Let’s Go to the Movies, by the Smithsonian

- Women Film Pioneers Project, by Columbia University Libraries

- The Lumière Cinématographe online exhibit, by Google Arts & Culture

- Phoenix’s Historic Theaters, by the Rogue Columnist

- School’s Out – our blog article about how turn of the century schools dealt with closures of all kinds

- The Wildly Diverse West – our blog article about how the American West was much more diverse than Hollywood portrayed

Information for this article was found online from these sources: PBS; NPR; the Met Museum; the History Channel; Science History; Business Insider; the University of Wisconsin; the University of Arkansas; the University of Minnesota; JSTOR Daily; the Hollywood Diversity Report; Movies Silently blog; Smithsonian Magazine; Time magazine; Hollywood Reporter; the Library of Congress; and the Chronicling America newspaper archives (Arizona Republic, Phoenix Tribune, Daily Arizona Silver Belt, Bisbee Daily Review, Tombstone Epitaph).

Archive

-

2025

-

January (1)

-

-

2024

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-