Making Music

Posted May 1, 2019

Written by Heather Roberts, Research Historian

Did you know…

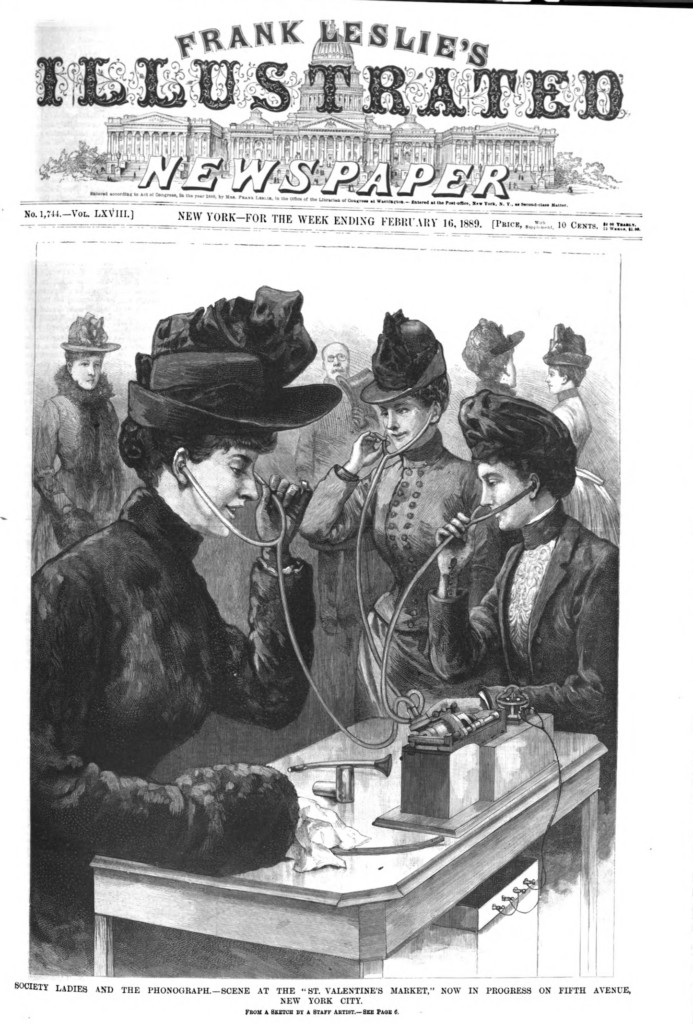

One of the most popular ways to listen to music in 1889 was, you guessed it, with headphones!

Today, listening to music is one of the easiest things we can do. With the touch of a button, you can crank the oldies station loud enough to annoy your kids for a few seconds before they pop in their headphones to listen to their endless supply of music you equally disregard. Ah, music, bringing families together! *sniff*

But listening to music hasn’t always been so effortless. In fact, for the vast majority of human history, if you wanted to listen to music, you would have to make it yourself. We don’t have musical instruments in the Rosson House (an organ, piano, and zither for those who are counting) just because they’re pretty or because they’re from the correct time period! These are instruments that would have been used on a daily or weekly basis, to entertain family and friends, and even to play at public musicals, dances, and recitals. The ability to play music well was fervently admired, and (particularly for women in upper class families) no education was considered complete without the study of music.

We know that the Goldbergs owned a piano, and we know how much they paid for it – $650 – because the purchase was reported in the Arizona Republican newspaper on September 24, 1893. (Side Note: In 1893, $650 was worth what is a little over $18,000 in 2019 when this article was written, and over $22,000 in 2024. We’ll give you a moment here to lift your jaw up off the floor, just like we had to…Whew!) Pianos weren’t the only instruments you could play, however, and the Sears Roebuck and Montgomery Ward catalogs sold not only pianos, but organs, accordions, violins, coronets, trombones, drums, and anything else you’d hope your neighbor’s kids weren’t learning how to play in their backyard.

If you didn’t know how to play an instrument, there was eventually an alternative to listening to music in your house. The phonautograph, a machine that recorded images from sounds by tracing squiggles in black soot, was patented in 1857 by French inventor Edouard-Leon Scott de Martinville. Twenty years later, Thomas Edison patented a more marketable product – the phonograph, which played recorded sound etched first into aluminum, and then wax cylinders. This marvel could not only play music (about 2 minutes total from one cylinder), but many phonographs came with a separate component that could record sound as well. You could listen to your favorite song, and then record a greeting to a loved one who lived far away. It was truly revolutionary! But cylinders were problematic – they couldn’t fully record or play a piece of music longer than 2 minutes, they tended to develop mold, and they took much longer make, having to etch each one individually.

The Edison Home Phonograph (c.1906) from the back parlor of the Rosson House.

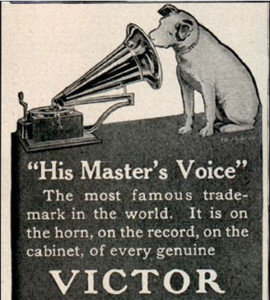

In 1887, an immigrant named Emile Berliner stepped in with a solution to the cylinder problem – the invention of the gramophone and flat record. Records had the advantage of having two sides, which meant they had twice the amount of music. But more importantly, they could be quickly mass-produced. Berliner was able to sell his idea to the Victor Talking Machine Company, who used his design to successfully sell gramophones and records in the US. They also used an image of his dog, Nipper, in their marketing campaigns. You might recognize him in this ad below (c.1920).

Four years after the Goldbergs bought their piano, the Sears Roebuck catalog had a gramophone for sale for $35 (or just over $1,000 today), which included the cone to project sound, a set of hearing tubes for three people (hello headphones!), and 12 records to listen to. While still expensive, it was a much more realistic purchase for middle class families. There were other records you could buy, including many made for dancing (polkas, waltzes, and quadrilles), a selection of songs from operas, and a plethora of John Philip Sousa marches – all for the low, low price of 50 cents each (there were discounts for orders of 12 or more records, and for cash orders).

Gramophones, later known as record players of course, had lost their popularity by the 1980s and 90s, but records are now making a comeback. Listening to them will never be as easy as turning on the radio (Phoenix’s first radio station was licensed in 1922, by the way) or tapping that icon on your phone, but they have a sound that can take you back to another time. The Library of Congress has an interesting and extensive digital collection of audio recordings you can browse through (https://www.loc.gov/audio) and even download. It’s truly amazing to hear a piece of music, story, or a speech that was recorded over a century ago.

Gramophones, later known as record players of course, had lost their popularity by the 1980s and 90s, but records are now making a comeback. Listening to them will never be as easy as turning on the radio (Phoenix’s first radio station was licensed in 1922, by the way) or tapping that icon on your phone, but they have a sound that can take you back to another time. The Library of Congress has an interesting and extensive digital collection of audio recordings you can browse through (https://www.loc.gov/audio) and even download. It’s truly amazing to hear a piece of music, story, or a speech that was recorded over a century ago.

Information on early Victorian parlor music and on Mr. Edison’s phonograph were found online at the Library of Congress.

Information about the phonautograph was found from this story on NPR.

Information on Mr. Berliner and his gramophone was found online at Thought Co.

HathiTrust digital library is where we found the catalogs noted in this blog, including the great picture of the ladies with headphones from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (February 16, 1889). We used information from the 1897 Sears Roebuck catalog and the 1916 Montgomery Ward catalog.

The piano pictured at the top of the page is a Collard & Collard, London, burled walnut piano (c.1824), from the back parlor of the Rosson House.

Archive

-

2025

-

January (1)

-

-

2024

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-