“…Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

– “The New Colossus,” poem written in 1883 by Jewish immigrant Emma Lazarus, engraved on the base of the Statue of Liberty

Immigration Nation

For a printable version of this article, please click here.

Did you know…

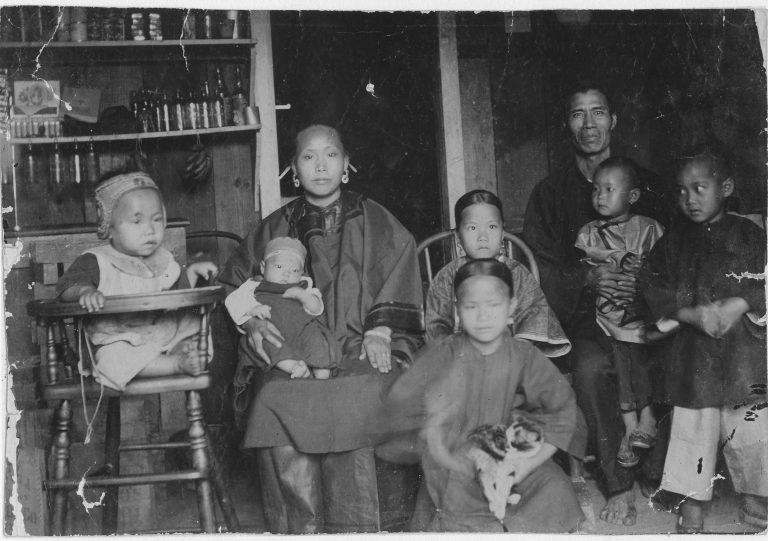

Chinese immigrant family, c1893, Hawaii State Archives.

When the US became a nation, its leaders immediately began deciding who could become a citizen and who couldn’t. The 1790 Naturalization Act required people who wanted to become citizens to have lived in America for two years and be “of good moral character.” It also mandated new citizens be “free” and white, denying citizenship to Native Americans and to African Americans, whether they were enslaved or not. The Alien and Sedition Acts (1798) allowed for the arrest, imprisonment, and deportation of foreign-born people during wartime for no reason other than their country of birth. This would, over 140 years later, become the justification for Executive Order 9066, incarcerating Americans of Japanese descent during World War II. In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed, banning immigrants from China outright for ten years, and refusing citizenship to those who were already in the US. The 1907 Immigration Act barred immigrants with mental and physical disabilities, and the Immigration Act of 1917 created literacy tests for immigrants 16 years and older. It also outright banned immigrants from India, Indochina, Afghanistan, Arabia, the East Indies, and more. The Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 created an immigrant quota system, restricting each nationality to 2% of their listed amount in the 1890 census, and limiting the total amount of immigrants each year to just 165,000. This law was still in place at the beginning of World War II in Europe, and was responsible for turning away many Jewish people who hoped to escape to the US, including Anne Frank and her family.

Still, waves of immigrants came to America over the years, fleeing their former homes for economic reasons (taxes, job shortages, drought and famine) and/or for religious or political ones (persecution, violence). They were drawn by promises of jobs, cheap farmland, and also the California Gold Rush (1849). The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the biggest increase in people emigrating to the US, though – from 1850 to 1913 over 30 million immigrants came to America in search of a better life, and by 1910, about 22% of American workers were immigrants. So many people were emigrating, in New York in 1892 the federal government established Ellis Island as an official immigration station, which would eventually process over 12 million immigrants in the 62 years it was in operation. On the west coast, Angel Island was the immigration station in San Francisco, processing an estimated 1 million immigrants between 1910 and 1940.

Immigrants at Ellis Island, c1910, Library of Congress.

At the turn of the century, the Arizona Territory population was much like Arizona’s is today, where the majority of people living here come from somewhere else. In 2019, over 60% of Arizonans were born in a different state, and 13.4% of Arizona’s population was born in a different country. Almost 100 years before, immigrants constituted almost a quarter of Arizona’s population (80,566 out of 334,162). All but one owner of Rosson House were born in different states – the Rossons were from Virginia and Texas, the Goldbergs from California, the Higleys from Ohio and Illinois, and Billie Gammel was from Georgia, leaving Frankie Gammel the only one born in Arizona. Of all their parents, most were also born in the US except for Frankie’s mother (Mexico), and Aaron and Carrie Goldberg’s parents (his were from Russia and hers from Germany). But there were other people who lived at Rosson House over the years who were immigrants, starting with the Goldbergs, who had two foreign-born lodgers living with them at the House when the 1900 census was taken – Louis Migel from Russia (who was also Aaron’s brother-in-law), and Henry Christoph from Holland. The Gammels, for whom we have three consecutive decades of census information while they lived at Rosson House, also had lodgers live with them who were foreign-born: In 1920, Jack Morgan (Australia), John Irwin (Ireland), Gus Guzunis (Greece), and Billie Orreges (Greece) are all recorded as lodgers at Rosson House; Ascension Perez (Mexico) is listed as living there in the 1930 and 1940 censuses, along with 24 years of Phoenix City Directories (1923 to 1947). And we can’t forget our very own Kai “Speedy” Skounborg, who came to the US from Denmark in 1912, rented rooms at Rosson House from around 1963 to early 1975, and then stayed on as a caretaker of the Square, living here in a trailer until his death in 1981.

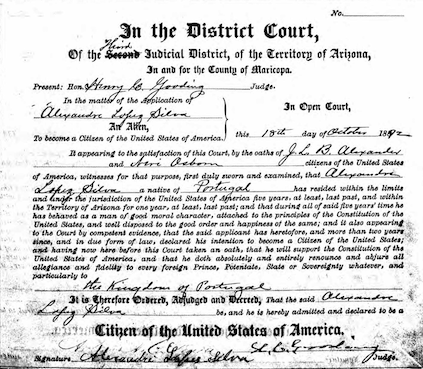

Immigrants also had a big impact in the other buildings at The Square. When the Rossons sold land on the south side of Block 14, they were selling it to immigrants – Leon Bouvier emigrated from French Canada in 1872, Albrecht Frederick Conrad Kirchoff from Germany in 1875 (his wife, Bertha, emigrated from Germany in 1885), and Constance Stevens from England in 1888. Two out of those three also sold their properties to immigrants – Constance to Edward Haustgen, who emigrated from Luxembourg in 1906, and Conrad to Alejandro and Mary Silva (he emigrated from Portugal in 1882, and she from Mexico in 1874). Edward is listed in the 1910 census as living at 613 East Adams with a roommate from France (they were possibly living across the street from the Stevens-Haustgen House at 614, or maybe at the Teeter Carriage House??), and many of Edward’s foreign-born relatives lived at The Square (listed in the 1920 and/or subsequent censuses), including his mother (Mary Haustgen), his sisters (Marguerite and Anna Haustgen), his nephews (George Bernard and Frank Conter), and his niece (Mary Conter). We’re not sure if Alejandro ever lived at The Square, though Mary lived at Silva House with their nieces (Frances Miramon and Marion Silva) after his death. Like the Gammels, the Haustgens and the Silvas rented out rooms at least once to lodgers who were immigrants – in 1920, John Powers (Canada) rented a room from the Haustgens, and Isadore Coppro (Italy) rented a room from the Silvas. (FYI – Leon Bouvier owned the Bouvier-Teeter House; the Kirchoff family owned Silva House; Constance Stevens owned the Stevens and the Stevens-Haustgen Houses; Marguerite Haustgen built/owned the Duplex as a rental property in 1922; and Kathryn Baird of the Baird Machine Shop/Pizzeria Bianco was from Arizona, but her parents were immigrants from England.)

Alejandro Silva’s naturalization papers, dated October 18, 1892.

Taking a quick look through the few pages of census records from 1880 through 1950 from the areas surrounding The Square, they show a plethora of immigrant neighbors, from just about every country you could imagine. Mexico was (and is) the most common country immigrants were/are from, but the countries listed also include those listed in the paragraph above, as well as China, Ireland, Syria, Lithuania, Switzerland, Russia, Spain, Hungary, Egypt, Romania, Norway, Turkey, Austria, Sweden, Greece, Northern Ireland, Poland, Scotland, and Venezuela. These immigrants were investors, ranchers, liquor store owners, shop keepers, seamstresses, store clerks, bakers, miners, homemakers, stone masons, bookkeepers, retailers, cooks, stable hands, physicians, bartenders, students, carpenters, teamsters, hotel keepers, horticulturalists, tailors, waiters, hat cleaners, auto mechanics, saloon keepers, teachers, laundry workers, salespeople, engineers, cattlemen, builders, ministers, shoe makers, farm workers, merchants, machinists, laborers, and brewers (one of whom would go on to become Mayor of Prescott).

Throughout US history the influx of people from foreign countries has resulted in racist and xenophobic attacks on current immigrants (and/or their descendants) by former immigrants (and/or their descendants). New immigrants have often been paid less for the same jobs, or hired for jobs that no one else wanted. Groups afraid of losing their economic and social standing combined that fear with racial or ethnic hatred, and have struck out against anyone they see as newcomers – people have burned immigrants’ housing, churches, and businesses, and terrorized, forcibly relocated, beaten, and even murdered them – often never being punished for these appalling acts of violence. It happened to Irish immigrants in the Philadelphia Nativist Riots of 1844; to Chinese immigrants in Denver, CO (1880), Rock Springs, WY (1885), and Seattle, WA (1886); to 2 million Latinos across the country, most of whom were American citizens, who were involuntarily “repatriated” to Mexico during the Great Depression; and to six women of Asian descent on March 16, 2021 in Atlanta, Georgia.

The massacre of the Chinese at Rock Springs, Wyoming / drawn by T. de Thulstrup from photographs by Lieutenant C.A. Booth, Seventh United States Infantry, Library of Congress collection.

Arizona owns a continuing part of that history, too. In the year Rosson House was built, the introductory page of the Phoenix City Directory stated that the volume did not include the names of people who were “Chinese or any other objectionable classes”. In 1921, when nearly a quarter of Phoenix’s population was foreign-born, the directory disparaged “Mexicans, negros, (and) foreigners”. Almost a century later, the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office was found guilty of racially profiling Latinos and anyone else who they thought looked or sounded “foreign”.

As our city continues to grow, our diversity remains one of its greatest strengths. With over 40% of residents identifying as Latino, and nearly 20% foreign-born, Phoenix stands as a testament to the resilience, contributions, and interconnected histories of those who have shaped it.

Learn more about who lived at The Square in 1950 from our article about that year’s census; about the life of Kai “Speedy” Skounborg from our article, Fun on Wheels – Speedy’s Story; about the history of our state during the 1930s from our article, Arizona and the Great Depression; and about the Silva family from our in-person and online exhibit, The Silva Family of Heritage Square: Immigrants & Pioneers.

Explore US immigration in the 20th century from the very important PBS Ken Burns special, The US and the Holocaust.

Information for this article was found online in the US Censuses from 1880 through 1950; Population Demographics from the Census Bureau; Library of Congress – Immigration to the US, 1851-1900, Intolerance; the History Channel – Immigration Before 1965; the Office of the Historian (US Dept. of State) – The Johnson-Reed Act; PEW Research – How Immigration Laws and Rules Have Changed Through History; the National Archives – Executive Order 9066, and the Chinese Exclusion Act; Wyoming History – The Rock Springs Massacre; PBS Destination America Immigrants; Smithsonian Magazine – How the 19th Century Know-Nothing Party Reshaped American Politics; Stanford News – …Historical Age of Mass Migration; the National Park Service – Chinese Labor and the Iron Road, Angel Island, and Ellis Island; Philadelphia Encyclopedia – Nativist Riots; Oxford Research Encyclopedias – Mexican Immigration to the United States, and the Arizona Daily Star.

Archive

-

2025

-

January (1)

-

-

2024

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-