Hair We Are

Posted October 1, 2021

Written by Heather Roberts, Research Historian

For a printable version of this article, please click here.

Did you know…

Hair wreath, c1870, Heritage Square collection

Since we’re all celebrating October and the return to cooler temperatures and spooky stories this month, we thought this would be the perfect time to talk about something at Rosson House that gives people the willies, the heebie jeebies, and the chills. We’re talking about the hair art from our collection – specifically the necklace and the wreath we have on display at Rosson House. These artifacts are truly interesting examples of artifacts that either fascinate or repulse people, and sometimes a little of both!

Today, most of the objects in our lives are made of plastics, but Victorians used natural materials in their everyday lives (i.e. – hair, antlers, shells, horns, feathers, hides/furs and bones), as people did in general, dating back thousands of years. When the 5,300 year-old mummy of Ötzi the Iceman was discovered in the Italian Alps, his clothes were made of leather and hide, and were stitched together with animal sinews. Amongst his belongings, tools made of antlers were found. Fast-forward to the 19th century, and you’d find Victorians wearing kid gloves (“kid” meaning “baby goat” in this case), top hats made of beaver pelts, hair combs made of tortoise shell, and corsets supported by whalebones. For better or worse, today’s lack of objects made of these types of natural materials might be part of the reason why hair art unnerves us.

Hair art was popular during the Victorian Era, but it dates back centuries before. In China, long hair was used in Buddhist embroidery during the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE). Around that same time in Europe, people started venerating hair clippings from Christian martyrs and saints (amongst other things like fingernail clippings, toes, heads, and entire skeletons!). During the Middle Ages, King Christian IV of Denmark presented his queen, Anna Catherine of Brandenburg, with a bracelet made of gold and his braided hair. People who couldn’t afford that luxury exchanged locks of hair to symbolize love or friendship. Hair was seen as very unique and personal, representing an individual in a way that nothing else could. Before photographs existed or were affordable to the masses, a lock of hair from a loved one could be the only tangible memory you had of that person – whether they moved far away, or more often, died.

-

Strands of Sorcery

Hair might have been saved as a keepsake throughout history, but it’s also been used in what’s called sympathetic or folk magic. Because hair is very unique to each individual, it was considered a powerful ingredient in spells. Running water over strands of an enemy’s hair or placing it in the knot of a tree that would grow up around it was said to cause insanity. Boiling a lock of your unfaithful lover’s hair in your own urine (ick!) and then burying it under the threshold would keep them by your side. But burying a bottle under your hearth that contained iron nails or copper pins, urine, and potentially hair, fingernail clippings, bone, wood, or thorns would protect a home from a witch’s curse. About a dozen witch bottles have been found in the United States, like this potential one pictured here from Virginia, which dates back to the US Civil War.

Hair might have been saved as a keepsake throughout history, but it’s also been used in what’s called sympathetic or folk magic. Because hair is very unique to each individual, it was considered a powerful ingredient in spells. Running water over strands of an enemy’s hair or placing it in the knot of a tree that would grow up around it was said to cause insanity. Boiling a lock of your unfaithful lover’s hair in your own urine (ick!) and then burying it under the threshold would keep them by your side. But burying a bottle under your hearth that contained iron nails or copper pins, urine, and potentially hair, fingernail clippings, bone, wood, or thorns would protect a home from a witch’s curse. About a dozen witch bottles have been found in the United States, like this potential one pictured here from Virginia, which dates back to the US Civil War.

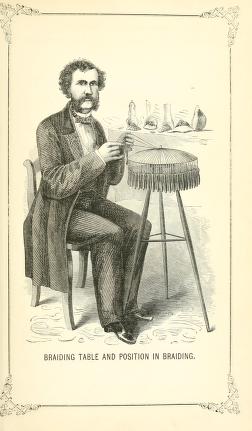

The popularity of hair art during the 19th century has everything to do with the mourning traditions of the influential and powerful woman who gave her name to that era: Queen Victoria herself. As a prominent and popular monarch, Victoria and/or her family started trends that last until this day, including brides wearing white dresses on their wedding day, and people bringing evergreen boughs and trees into their homes for Christmas. When Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, died in 1861, and she mourned his loss until she passed away 40 years later. Following the strict etiquette of mourning, the queen wore unrelenting black clothing along with a locket with Albert’s picture and a piece of his hair. At a time when mortality rates were high – antibiotics didn’t exist; inoculations/vaccines were in their infancy; and, here in the United States, soldiers were dying in the Civil War – and the popularity of memento mori hair art exploded. You could order hair art from a catalog (Catalogue of Designs for Artistic Hair Scenery and Ornaments, c1886, pictured at the top of the page), read a book on how to create a piece of jewelry or a wreath (Self-instructor in the Art of Hair Work by Mark Campbell, c1867; pictured to the right), or look through Godey’s Lady’s Book (magazine) for hair art designs and to buy the materials necessary to create it. Hair was used in art outside of mourning as well – women embroidered family tree samplers with hair from each living family member, and gifted pocket watch chains made of hair to husbands, fathers, or brothers. As hair art became popular, companies would offer up to $100 a pound for long, clean lengths of hair (see O. Henry’s story, The Gift of the Magi), and even up to $200 a pound for white or grey hair in good condition (used mostly in wigs).

The popularity of hair art during the 19th century has everything to do with the mourning traditions of the influential and powerful woman who gave her name to that era: Queen Victoria herself. As a prominent and popular monarch, Victoria and/or her family started trends that last until this day, including brides wearing white dresses on their wedding day, and people bringing evergreen boughs and trees into their homes for Christmas. When Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, died in 1861, and she mourned his loss until she passed away 40 years later. Following the strict etiquette of mourning, the queen wore unrelenting black clothing along with a locket with Albert’s picture and a piece of his hair. At a time when mortality rates were high – antibiotics didn’t exist; inoculations/vaccines were in their infancy; and, here in the United States, soldiers were dying in the Civil War – and the popularity of memento mori hair art exploded. You could order hair art from a catalog (Catalogue of Designs for Artistic Hair Scenery and Ornaments, c1886, pictured at the top of the page), read a book on how to create a piece of jewelry or a wreath (Self-instructor in the Art of Hair Work by Mark Campbell, c1867; pictured to the right), or look through Godey’s Lady’s Book (magazine) for hair art designs and to buy the materials necessary to create it. Hair was used in art outside of mourning as well – women embroidered family tree samplers with hair from each living family member, and gifted pocket watch chains made of hair to husbands, fathers, or brothers. As hair art became popular, companies would offer up to $100 a pound for long, clean lengths of hair (see O. Henry’s story, The Gift of the Magi), and even up to $200 a pound for white or grey hair in good condition (used mostly in wigs).

-

Hair-Raising Politics

During the late 18th century, women’s hairstyles among the European nobility were very artistic and elaborate. They would add wigs or hairpieces to their own hair, and style it up with paddings and wires to reach great heights. Their hair would then be decorated with powder, ribbon, jewels, feathers, or even entire birds – either dead and stuffed, or still alive in birdcages! Heavily criticized as shallow and excessive, these hairstyles were often actually political statements, like Ruth Bader Ginsberg’s collars or Madeleine Albright’s pins. When Louis XVI of France and the successors to his throne were successfully inoculated against smallpox in 1774, Marie Antionette wore her hair in a style called, “le pouf à l’inoculation” (the hairstyle of the inoculation) to celebrate. The style consisted of the serpent of Asclepius (portraying medicine), a club (portraying conquest), a rising sun (portraying the king), and an olive branch (portraying peace and joy). She would also wear her hair in the style pictured here, called the, “Coëffure à l’Indépendance ou le Triomphe de la Liberté” (Hairstyle of Independence or the Triumph of Freedom). It celebrated the June 17, 1778 American Revolutionary War naval battle between the French frigate, Belle Poule, and the English frigate, Arethuse. In both instances – inoculations (like today, people were sometimes more afraid of the cure than they were of the deadly disease) and the American Revolution (the cost of supporting the colonists was expensive) – the queen took a subject that was divisive and showed her support.

During the late 18th century, women’s hairstyles among the European nobility were very artistic and elaborate. They would add wigs or hairpieces to their own hair, and style it up with paddings and wires to reach great heights. Their hair would then be decorated with powder, ribbon, jewels, feathers, or even entire birds – either dead and stuffed, or still alive in birdcages! Heavily criticized as shallow and excessive, these hairstyles were often actually political statements, like Ruth Bader Ginsberg’s collars or Madeleine Albright’s pins. When Louis XVI of France and the successors to his throne were successfully inoculated against smallpox in 1774, Marie Antionette wore her hair in a style called, “le pouf à l’inoculation” (the hairstyle of the inoculation) to celebrate. The style consisted of the serpent of Asclepius (portraying medicine), a club (portraying conquest), a rising sun (portraying the king), and an olive branch (portraying peace and joy). She would also wear her hair in the style pictured here, called the, “Coëffure à l’Indépendance ou le Triomphe de la Liberté” (Hairstyle of Independence or the Triumph of Freedom). It celebrated the June 17, 1778 American Revolutionary War naval battle between the French frigate, Belle Poule, and the English frigate, Arethuse. In both instances – inoculations (like today, people were sometimes more afraid of the cure than they were of the deadly disease) and the American Revolution (the cost of supporting the colonists was expensive) – the queen took a subject that was divisive and showed her support.

Hair art fell out of style around World War I, along with Victorian Era homes (ahem!!), clothing, and anything else from that age that was seen as sentimental, excessive, and overly ornamented. Locks of hair as keepsakes are still popular in some instances, though. For example, many parents keep a lock of hair from their child’s first haircut (full disclosure – this author did!). And a quick search online shows that locks of hair from celebrities are definitely in demand – just weeks after David Bowie died in 2016, a lock of his hair sold for $18,000, and in 2002 a lock of Elvis’s hair went for $115,120! You can look up organizations like Victorian Hairworkers International and the Morbid Anatomy Museum, who are trying to bring hair art back to the mainstream.

Information for this article was found online from these sources: Smithsonian Magazine articles on Victorian Hair Art and Lincoln’s Hair Wreath; Jstor articles on Witch Bottles and Chinese Hair Embroidery; the Morris County Historical Society; Witchcraft in Illinois: A Cultural History (2017), by Michael Kleen; William & Mary; Horniman Museum & Gardens; Dilettante Army; Business Insider (celebrity hair); Notes from the Frontier; the Chertsey Museum; the Fashion Historian; the Costume Society; and The Atlantic.

Archive

-

2025

-

January (1)

-

-

2024

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-