Fun on Wheels – Speedy's Story

Posted September 1, 2024

Written by Heather Roberts, Research Historian

For a printable, PDF version of this article, please click here.

There are many names that Kai “Speedy” Skounborg used during his lifetime – some on accident, like the varied spellings and/or misspellings of his last name, and some, like “Speedy”, on purpose. For the sake of continuity, he will be referred to for the majority of this article by the name he is fondly remembered by here at The Square – Speedy.

Also, see Speedy in the news with our image gallery of some of Speedy’s Newspaper Clippings.

Did you know…

COMING TO AMERICA

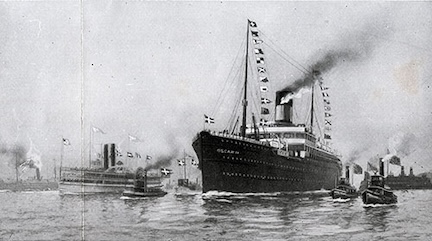

The Oscar II of the Scandinavian America line – this was the ship that brought Speedy and his family to the United States. Photo from the Gjenvick-Gjønvik Archives website.

Kai Thomas Skounborg, otherwise known as Speedy, was born to Margrethe and Niels Skounborg in Copenhagen, Denmark on December 6, 1910. Niels, an automobile mechanic and bicycle maker, Margrethe, and their children – Angelo (3), Speedy, (almost 2), and Aage (2 months) – emigrated to the United States in late 1912. They crossed the Atlantic aboard the SS Oscar II of the Scandinavian America line – a ship with a capacity of 1,170 passengers – and likely stayed in a third class berth. Ships within the Scandinavian America line were supplied with life preservers and life boats in numbers over and above the number of passengers and crew on board. (Note – With the sinking of the Titanic in April that year, this is something that was likely comforting to the Skounborgs and their fellow passengers.) In addition to increased safety, traveling third class was fairly comfortable on the Oscar II. Third class passengers were not housed in steerage, unlike ships from other lines, and could choose rooms with up to 4 bunk beds – handy when you’re a family of five! A 1912 brochure from the line, specifically directed towards potential third class passengers, promoted their free healthcare for anyone who fell ill on the voyage, separate cabins for families, roomy dining areas, and considerable walking spaces. (Note: View text and several pictures from the 1912 Scandinavian America line brochure from the Gjenvick-Gjønvik Archives website.)

The Skounborgs arrived in New York on October 2, 1912, and, like so many others, were processed through Ellis Island, giving Sioux City, Iowa as their intended destination. They arrived in America, just 5 of the over 800,000 immigrants to reach the US that year, and part of a wider migration to the States that, from 1850 to 1913, would see 30 million people come to America in search of a better life. By 1910, just two years before the Skounborgs landed in New York, about 22% of all American workers were immigrants.

The Skounborgs choice of the Midwest as a home was the same one many Germanic and Scandinavian Americans made, building communities around shared backgrounds, languages, and religions. But with laws at the time like the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882), and the 1907 and 1917 Immigration Acts, there was pushback on immigration to the United States from people who were former immigrants and/or descendants of immigrants. This was made worse in 1917 when the US entered World War I. With anti-German hysteria fueling attacks on German immigrants and even on people from Scandinavian and Eastern European countries that could be perceived as “German” to those who were looking for people to scapegoat. The KKK, who were seeing a resurgence at this time, made the news for threatening and attacking anyone who they perceived as not being patriotic enough during the war. This included immigrants, people of color, and everyday workers seeking fair employment practices. Iowa banned use of any foreign language in public, including in businesses, schools, churches, and even over the phone, and many other states passed anti-German laws as well, which, like Iowa’s ban, would affect all immigrants.

By the late teens, the Skounborgs were living in Superior, Nebraska, and Speedy’s father, Niels, was part owner of the Motor Inn – “Automobile Accessories, Expert Repairing and Machine Work”. Like many other immigrants, and all men in the United States between the ages of 18 and 45, Niels registered for the draft in June 1917. (Note: Though his draft number was never chosen, over 18 percent of the US Army were immigrants.) The family’s next stop was Denver, Colorado, where Niels also co-owned the South Broadway General Auto Service Co. at 160 South Broadway (Note: Constructed in 1906, the building still exists and is now a scooter store), and where the family eventually owned their own home at 432 S. Pearl St (pictured to the right). Niels was granted citizenship in February 1927 for himself, Margrethe, and their children, which by this time included Angelo (17), Speedy (16), and Aage (14), and also Ellen (10), Rose (6), and Carl (3).

By the late teens, the Skounborgs were living in Superior, Nebraska, and Speedy’s father, Niels, was part owner of the Motor Inn – “Automobile Accessories, Expert Repairing and Machine Work”. Like many other immigrants, and all men in the United States between the ages of 18 and 45, Niels registered for the draft in June 1917. (Note: Though his draft number was never chosen, over 18 percent of the US Army were immigrants.) The family’s next stop was Denver, Colorado, where Niels also co-owned the South Broadway General Auto Service Co. at 160 South Broadway (Note: Constructed in 1906, the building still exists and is now a scooter store), and where the family eventually owned their own home at 432 S. Pearl St (pictured to the right). Niels was granted citizenship in February 1927 for himself, Margrethe, and their children, which by this time included Angelo (17), Speedy (16), and Aage (14), and also Ellen (10), Rose (6), and Carl (3).

SPEC & SPOT

“The opening (act) is with Spec & Spot, unicyclists. They can do more

perched low or high on one wheel than most can do on two.”

– The Lincoln Star, Lincoln, Nebraska, May 8, 1936

Though Speedy was listed in both the 1930 census and the city directories in the early 1930s as a magazine salesman, he and Angelo, who was listed in both as a carpenter, were already making a name for themselves as unicycle experts. We’re not sure when they began riding the unicycle, but we do know that when Speedy was 18, he unicycled to the top of Lookout Mountain in the Denver area. The Rocky Mountain News reported that it took Speedy (as Kai Skounborg) about one hour and thirteen minutes to make it to the top of the 7,377 foot peak. A year later, he and his older brother, Angelo, were talking of a unicycle trip up Pikes Peak, which is almost twice the height of Lookout Mountain!

The brothers entered unicycling contests and performed in Colorado, but by 1932 they were branching out to performing in other states. The first mention we could find of Speedy and Angelo doing a show under the names of “Spec & Spot” was in the Oakland Tribune (July 16, 1932) at a benefit at The Roxie. They were crowned the “Rocky Mountain Unicycle Champions” at an event in Greeley, Colorado in 1934, and things kind of snowballed for them after that. They traveled all over the United States and parts of Canada, doing unicycle and bicycle tricks with a comedic flair at state fairs and festivals, night clubs, and even a mobster’s café in Chicago. In 1937, the duo caught a ship headed for Brazil and performed there at the Casino Balneário da Urca in February and March, returning to the States in April.

The brothers entered unicycling contests and performed in Colorado, but by 1932 they were branching out to performing in other states. The first mention we could find of Speedy and Angelo doing a show under the names of “Spec & Spot” was in the Oakland Tribune (July 16, 1932) at a benefit at The Roxie. They were crowned the “Rocky Mountain Unicycle Champions” at an event in Greeley, Colorado in 1934, and things kind of snowballed for them after that. They traveled all over the United States and parts of Canada, doing unicycle and bicycle tricks with a comedic flair at state fairs and festivals, night clubs, and even a mobster’s café in Chicago. In 1937, the duo caught a ship headed for Brazil and performed there at the Casino Balneário da Urca in February and March, returning to the States in April.

The act the brothers were putting on was pure vaudeville – a popular form of entertainment in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that included a variety of performers like comedians, musicians, jugglers, actors, ventriloquists, high wire acts and trapeze artists, magicians, dancers, sword swallowers, and so much more. Spec & Spot’s unique mixture of cycling stunts and comedy fit right in. At its height in the years before World War I, vaudeville shows were seen in thousands of theaters across the country, and employed tens of thousands of people. But wasn’t an easy life for the people doing the entertaining, spending much of their on the road, traveling from job to job and town to town, and it wasn’t particularly high paying, unless you were one of the top performers. In the 1930s the popularity of vaudeville started waning as the combination of radio shows, movies, and eventually television would ultimately end the former entertainment titan.

Spec & Spot were performing in New York City at the American Music Hall on East 55th Street later in 1937 when, on November 26th, Speedy got married to Jeanne DuVal, a showgirl and immigrant from Montreal, Canada. The addresses given on the marriage certificate shows them living within a few minutes’ walk of each other, in the heart of the New York Theater District. There’s no record, however, of their marriage outside of the initial certificate, or of a divorce. After Speedy and Angelo left New York, they performed in Washington, DC over the New Year, and went on to jobs in Chicago, Missouri, and Ohio in 1938.

ON WITH THE SHOW

“Spec Thomas (has an) outstanding unicycle act with a clever routine called Fun on Wheels.”

– Jefferson Sentinel, Lakewood, Colorado, September 27, 1950

Speedy and Angelo were still traveling and entertaining together as Spec & Spot through August 1940. On September 4, 1940, Angelo married Ila Usher of Dixon, Pennsylvania in Lucas, Ohio. Ila was a dancer, and the two must have met while on the road for a show. After that, it seems the brothers’ careers parted ways.

Though we couldn’t find either brother in the 1940 census, their Draft Registration Cards, filled out in October 1940, place Angelo in Los Angeles, California and Speedy at the Union Mission in Norfolk, Virginia – a shelter for the unhoused – though his residence on the card was later updated to his parents’ address in LA.

Though we couldn’t find either brother in the 1940 census, their Draft Registration Cards, filled out in October 1940, place Angelo in Los Angeles, California and Speedy at the Union Mission in Norfolk, Virginia – a shelter for the unhoused – though his residence on the card was later updated to his parents’ address in LA.

From there on, for shows Speedy was known as “Spec Thomas”, putting together the familiar unicycling nickname “Spec” from “Spec & Spot” with his middle name, Thomas. He seems to have been just as popular being solo act, with mentions in newspapers across the country. In 1942, he had stayed in Reno, Nevada for a couple of jobs that lasted the first 5 months of the year – a rare occurrence – and he was billed as the “King of Cycle”, the “Talk of the Town Bicycle Act” and the “Unicycle Champ of (the) USA”. But in May, his draft number was called, and he was off to basic training. And while you’d think that would be the end of his unicycling days for a while, to the contrary – Speedy’s most famous unicycling moment that got the most press of his entire career happened while he was in uniform. His picture and caption (seen here) appeared in multiple newspapers across 39 states from Waterville, Maine, to Fairbanks, Alaska, and was also included in papers from 2 Canadian provinces.

We don’t really know anything else about Speedy’s service during World War II. His occupation was listed as “actor” on his enlistment records (as was Angelo), and he was obviously providing entertainment at some point by riding his unicycle. He was discharged from the Army on December 22, 1943. In the war years afterwards, Speedy performed at the Starlight Café and the Mocambo, both famous clubs that hosted Hollywood stars both on stage and in the crowd, and at The Tropics in Reno, Nevada. He then falls off the “news” radar – showing up in voter registration records for Los Angeles, California in 1948 and 1950, and in the 1950 census in Miles City, Montana, traveling through as a salesman – which must have been his fallback plan when performing jobs were few and far between – and, interestingly, he was also listed as a married man.

Speedy as “Spec Thomas” was back, in the 1950s, touring the country and making people laugh. Though he would occasionally pop up in places like Virginia, Texas, or Louisiana, he started out that decade in Nebraska and Colorado, bringing him back to areas familiar to him from his childhood. Notably, he was in Denver in March 1950 for a performance as “The great Spec Thomas, marvel of wheel balancing acts” at the Wallace Simpson American Legion Post 29 – a post located in Denver’s redlined Five Points neighborhood, and named after the first Black soldier from Colorado to die in combat during World War I. He spent most of that year in Colorado, but also gravitated to other Midwestern states like Iowa, Wisconsin, Minnesota, South Dakota, and more – they offered many job opportunities at fairs and festivals looking to hire entertainment acts. Whether it was an annual Corn Roast in Paxton, Illinois, or a Shrine Circus in Des Moines, Iowa, people loved Speedy’s shows, reporting his performances as “particularly delighting to the youngsters”. In 1955, a newspaper in Grand Island, Nebraska said that “Spec Thomas (was a) master of unicycling, who has been on several TV programs, and has every kind of thrill on bicycle and unicycle”. (Note – Before you ask, we’re disappointed to report that we have not yet been able to find any TV shows on which Speedy may have performed, but we’ll keep looking!)

Speedy performed in several similar venues throughout the 50s, and then changed up his act again by 1960, appearing in front of audiences as “Speedy the Clown”. The audiences were a bit smaller and the venues not quite so grand, but the enjoyment and laughter were heartfelt. The last two of his performances (that we know of) were right here in Phoenix, in October and December 1963. At the latter of the two, he brought holiday cheer to a group of disabled and underprivileged children, and a picture of Speedy perched atop a unicycle with one lucky kid on his shoulders, having the ride of his life, made the front page of the Arizona Republic.

COMING HOME

The story Speedy told was that he was driving around Phoenix one day, passed by Rosson House, and immediately wanted to live here. For those of you who’ve seen photos of what this house looked like by the early 1960s, you’ll understand that his feeling says a lot about Speedy’s ability to see the promise in a building that had definitely seen better days. Speedy made the old boarding house his home for a dozen years – longer than all but one of the original families who owned Rosson House. We’re not sure which room was his, but we do know he paid $15 a month in rent for a room on of the “upper floors”. Putting those two facts together, we believe that means Speedy’s room was in the attic – the two boarders whose rent amount we also know paid $28 and $40 a month for rooms on the second and first floors, respectively.

The Square remained his home for the rest of Speedy’s life. When the rest of the boarders left and the work on Rosson House began, Speedy was kept on as a caretaker, living in a trailer on site to keep an eye on the construction and on these local landmarks. He helped out with restoration work, wearing a helmet with chipped paint that read “Rosson Heritage House,” and using a cart with his name painted on the side. When the Museum was finally opened, he helped with that as well, occasionally giving tours, and unlocking doors in the morning and locking them back up at night. Longtime volunteer, Vicki Beaver, remembers him as always cheerful, and said he would sometimes play the organ for the docents at the end of the day. She said volunteers had been told not to play the organ, but no one told Speedy that because, “We were in his house!”

Speedy’s death on January 25, 1981, at the hands of someone who was trying to rob him came as a shock. How could such a well-liked person be a victim of such needless gun violence? Restoration Committee member and former mayor of Phoenix, John Driggs, was quoted in the Arizona Republic, saying, “(Speedy) added an important dimension to the restoration because of his familiarity with the house. He wanted to be a part of it. It was the high point of his life to see that house being restored…I didn’t think someone like him would have an enemy in the world.”

As was fitting, Speedy’s memorial took place right here at the Square, in the shadow of his favorite house.

Keep an eye out at our Memorial Rose Garden for a rose dedicated to Kai ‘Speedy’ Skounborg, comedian, entertainer, and caretaker of Rosson House.

And remember make sure you see what Speedy was up to during his career with our image gallery of some of Speedy’s Newspaper Clippings.

The majority of the information for this article was gathered from searching through Ancestry for primary documents relating to Speedy and his family, and from an exhaustive search through Newspapers.com, the Chronicling America Digital Newspaper Archive, the California Digital Newspaper Collection, the Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection, and Internet Archive for newspaper and magazine ads and articles, following Speedy throughout his career as a performer and entertainer. Other information was gathered online at: Norway Heritage – The Scandinavian America Line; the Gjenvick-Gjønvik Archives – Oscar II Archival Collection; Ellis Island (National Park Service) – From Danish Blood to American Spirit; US Census – Historical Statistics of the United States, 1789-1945 (PDF); Heritage Square History Blog – Immigration Nation, and Arizona at War: World War I; Library of Congress – Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History: Scandinavian; University of Nebraska-Lincoln – Re-inventing the Wheel: Nebraska’s Immigration History; Iowa PBS – It’s the Law: Speak English Only!; US Citizenship & Immigration Services – Citizenship and Immigration During the First World War (PDF); Discover Denver – Survey Report: Broadway/South Broadway Commercial Corridor (PDF); University of Arizona – American Vaudeville Museum; PBS American Masters – Vaudeville; World War II Museum – Research Starters: The Draft and World War II; and 5280 magazine – Five Points: You Have Arrived.

Archive

-

2025

-

January (1)

-

-

2024

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-