By the Book

For a printable version of this article, please click here.

Did you know…

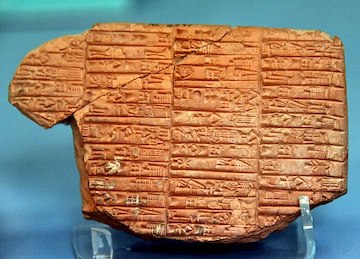

Clay tablet mentioning a list of goats, sheep, and lambs, dating to the 23rd century BCE, Nippur, Iraq (Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul).

There is just something about being in a library surrounded by books – the smell, the sound of the pages turning, the seemingly infinite amount of knowledge and number of stories just waiting to be explored. But the first libraries and archives predated books, as people used clay tablets to record their histories and information. Clay tablets dating as far back as 1000 BCE and 3000 BCE have been discovered in ancient records rooms in the Babylonian town of Nippur (now Iraq), and at Tell el-Amarna in Egypt.

Libraries as we know them were at first privately owned, by individuals or organizations (generally governments or churches – like this picture of the Admont Abbey Library in Austria, founded in 1072 CE by Benedictine monks) who were wealthy enough to be able to both afford books and to know how to read them. During the American colonial period, books had to be shipped from Europe, which led to their high cost. The first “public” libraries were available only to people who purchased memberships or subscriptions. Benjamin Franklin helped start the first of these in the American colonies, called the Library Company – each member had to invest 40 shillings to start, and 10 shillings each year to maintain their subscription. His library still exists today as a research library with its original books and many more.  (Fast Fact: Benjamin Franklin also created the first mail-order catalogue in the colonies in 1744, and it’s no surprise that was for buying books! The catalogue was essentially a list of books available for purchase – almost 600 of them in fact, including books on history, divinity, law, mathematics, philosophy, physics, and poetry. Read more about the history of catalogues from our December 2021 blog article, Mail-Order Catalogues.)

(Fast Fact: Benjamin Franklin also created the first mail-order catalogue in the colonies in 1744, and it’s no surprise that was for buying books! The catalogue was essentially a list of books available for purchase – almost 600 of them in fact, including books on history, divinity, law, mathematics, philosophy, physics, and poetry. Read more about the history of catalogues from our December 2021 blog article, Mail-Order Catalogues.)

-

Freedom to Read

The existence of libraries has not always equaled the freedom to read their contents. From segregation to banning books, the US has a significant history of making it more difficult to read. Libraries, particularly in the South, were segregated by law (as Arizona’s schools were until 1954). Separate but definitely not equal libraries, if they existed at all, were supplied mainly with outdated and/or worn books. Sit-ins in public libraries began in 1939 when five African American men entered a “whites only” library in Alexandria, VA and peacefully requested library cards, and continued in the 1960s with the Greenville Eight and the Tougaloo Nine (seen in this picture outside the Jackson Public Library, after their arrest in 1961). These nonviolent protestors were often attacked, beaten, and arrested, simply for trying to use the library, bringing to light to the inequality and injustice of segregation and the violence of racism. In 1964, the Civil Rights Act specifically outlawed racial discrimination in public facilities like libraries.

In order to stop people from reading, sometimes books are censored or banned. Governor William Bradford banned New English Canaan in 1634 for “lies, slanders, and calumnies” and arrested its author. Anti-slavery books like Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Appeal were banned and even burned in Southern states. When the Comstock Act was passed in 1873, it suppressed “the trade in, and circulation of, obscene literature and articles of immoral use.” This vague and non-specific language meant that virtually any book could be banned, including Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales and books by John Steinbeck, Ernest Hemmingway, D.H. Lawrence, and more. Though some books today are objected to because of language/profanity, nudity/sex, and violence, the vast majority of books that are unjustifiably targeted by books bans feature at least one of these topics: LGBTQ+ characters and/or identities, characters of color and/or race/racism in American history, or sex education. You can find these great books on Barnes & Noble’s Banned and Challenged Books List and can learn more about book bans and how to fight against them from the American Library Association website.

Public libraries started to spread through the US in the mid 19th century, supported by tax dollars instead of personal subscriptions or memberships, though Arizona Territory had its share of subscription libraries before the public ones were established. Local newspapers had ads for lending libraries in Tucson, Prescott, and Yuma as early as the 1870s. An ad in the Arizona Citizen promoted a library with books in German, English, and Spanish (September 8, 1877)! Many of these subscription libraries were located in newsstands that sold newspapers and magazines, like J.S. Mansfeld’s Pioneer News Depot (Tucson), the Tinker & Leonard News Depot & Circulating Library (Prescott); and at Schneider, Grierson & Co (Yuma), but they were also located at drug stores (Florence), parsonages (Flagstaff), and high schools (Phoenix). Newspapers would also report on library use, and what new books libraries were getting into circulation (a great idea!). The Arizona Territorial Library was established in 1864 in Prescott, the then-territorial capital, to house official books, records, and documents. It moved when the capital moved – to Tucson in 1867, back to Prescott in 1877, and finally to Phoenix in 1889 – and became the State Library in 1912 when Arizona became the 48th state. The oldest continuously operated public library in Arizona is the Copper Queen Library in Bisbee, AZ, open since 1882. Though Phoenix became the territorial capital in 1889, it didn’t have a public library until 1898, and only then thanks to local women from the Friday Club.

The Friday Club was established in 1897 by a group of 12 local women as a literary gathering. They researched historical events for later discussion at their meetings, and soon saw the need for Phoenix to have its own public library. To raise funds for the library, the Friday Club hosted teas, musical programs, lawn parties, and even a play. With this money, they were able to open a library with 1,000 books in two rooms at the Fleming building (built in 1883 at Washington and First Avenue, and torn down a century later), initially for their own use, but soon for the general public. The library moved into City Hall in 1899 and later its own building with grant money Phoenix received from Andrew Carnegie – a Victorian Era multi-millionaire steel magnate who used his money to improve his reputation and legacy by helping build over 1,700 libraries nationwide. The Phoenix Carnegie Library (now known as the Carnegie Center) opened in 1908 with 7,000 books. It was the only public library in the City of Phoenix until 1914, and served as the main branch of the Phoenix Public Library until 1952.

The Friday Club was established in 1897 by a group of 12 local women as a literary gathering. They researched historical events for later discussion at their meetings, and soon saw the need for Phoenix to have its own public library. To raise funds for the library, the Friday Club hosted teas, musical programs, lawn parties, and even a play. With this money, they were able to open a library with 1,000 books in two rooms at the Fleming building (built in 1883 at Washington and First Avenue, and torn down a century later), initially for their own use, but soon for the general public. The library moved into City Hall in 1899 and later its own building with grant money Phoenix received from Andrew Carnegie – a Victorian Era multi-millionaire steel magnate who used his money to improve his reputation and legacy by helping build over 1,700 libraries nationwide. The Phoenix Carnegie Library (now known as the Carnegie Center) opened in 1908 with 7,000 books. It was the only public library in the City of Phoenix until 1914, and served as the main branch of the Phoenix Public Library until 1952.

-

Libraries on the Front Lines

“No man and no force can take from the world the books that embody man’s eternal fight against tyranny. In this war, we know, books are weapons.” – Franklin D. Roosevelt, in reaction to Nazis burning books

“No man and no force can take from the world the books that embody man’s eternal fight against tyranny. In this war, we know, books are weapons.” – Franklin D. Roosevelt, in reaction to Nazis burning booksDuring the first and second World Wars, librarians went above and beyond to get books to soldiers on the front lines, as well as to those in hospitals and rehabilitation centers. The American Library Association established 36 camp libraries during World War I and distributed 10 million books and magazines. Over 1,000 librarians volunteered during the war to repair, distribute, and read books to soldiers. While the Nazis were banning and burning books prior to and during World War II, the US Victory Book Campaign did the opposite, distributing over 17 million books from 1941 to 1943. Though the majority of those books were sent overseas, some were sent to “war relocation” camps here in Arizona and in other states. San Diego children’s librarian Clara Breed even sent letters and books to the children she’d known and come to care for who were sent to the camps (learn more about Clara and see a collection of her letters online at the Japanese American National Museum).

Currently, Phoenix has 17 libraries, lending books, eBooks, and audiobooks, but also movies, music, WiFi hotspots, laptops, Culture Passes, and even seeds! And they’re not the only public library expanding their list of what they lend – locally, the Chandler library lets patrons use sewing machines, 3D printers, laser cutters, and professional studio equipment, and the Gilbert library lends out telescopes and prom dresses; the Albuquerque, NM library lends baking pans, and the Oakland, CA library lends out a whole collection of tools (home improvement, auto, and yard). Libraries all over have fun, educational programs for new readers, ESL learners, people who are learning computer literacy and coding, people who want to become US citizens, and more. They are truly priceless community resources!

Currently, Phoenix has 17 libraries, lending books, eBooks, and audiobooks, but also movies, music, WiFi hotspots, laptops, Culture Passes, and even seeds! And they’re not the only public library expanding their list of what they lend – locally, the Chandler library lets patrons use sewing machines, 3D printers, laser cutters, and professional studio equipment, and the Gilbert library lends out telescopes and prom dresses; the Albuquerque, NM library lends baking pans, and the Oakland, CA library lends out a whole collection of tools (home improvement, auto, and yard). Libraries all over have fun, educational programs for new readers, ESL learners, people who are learning computer literacy and coding, people who want to become US citizens, and more. They are truly priceless community resources!

-

Little Free Libraries

What started with one Little Free Library in Hudson, Wisconsin as a tribute to the founder’s mother is now a world-wide nonprofit agency, dedicated to building community, inspiring readers, and expanding book access for all. There are currently over 150,000 Little Free Libraries in more than 115 countries – including one here at Heritage Square! The next time you stop by the Square, grab a book from our Little Free Library (seen here just outside our Visitor Center) and leave one for someone else!

What started with one Little Free Library in Hudson, Wisconsin as a tribute to the founder’s mother is now a world-wide nonprofit agency, dedicated to building community, inspiring readers, and expanding book access for all. There are currently over 150,000 Little Free Libraries in more than 115 countries – including one here at Heritage Square! The next time you stop by the Square, grab a book from our Little Free Library (seen here just outside our Visitor Center) and leave one for someone else!

Information for this article was found online from the Digital Public Library of America’s online exhibit, A History of US Public Libraries; the Phoenix, Chandler, Gilbert, Albuquerque, and Oakland Public Libraries; articles from our own Donna Reiner in DTPHX.org and AZcentral.com, the Library of Congress – Chronicling America Digital Newspaper Archive; the City of Bisbee; Salt River Stories – Carnegie Library; the Arizona Historical Society – Friday Club; NPR – When America’s Librarians Went to War; the American Library Association – History, War Service Library book, Banned and Challenged Books; Oxford University Press blog – How libraries served soldiers…during WWI and WWII; ABC News San Diego; Illinois Library – Librarians in Uniform; Washington Post – American Book Banning Tradition…; Granville County Library – The Heroes of Desegregating in Public Libraries; CBS – The 50 Most Banned Books in America; Santa Clara University Library – The Hidden History of Libraries and Civil Rights; Little Free Libraries – History.

Archive

-

2025

-

January (1)

-

-

2024

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-