“Men are losing more than their jobs today: their self-respect and human dignity are all too often being endangered.” – Arizona Republic, October 7, 1932

Arizona and the Great Depression

For a printable version of this article, please click here.

Did you know…

Economically, World War I had been a boon for Arizona with the increase in demand for 3 out of its 5 Cs – copper, cotton, and beef (cattle). At that time, Arizona was producing 40% of copper mined in the US, and the price for copper almost doubled in the early years of the war (1914-16). The price for a bale of cotton went from $233 to $406 by late 1918. But after the war ended, the military cancelled many contracts and the extreme drop in the values of cotton, cattle, and copper, along with a pink bollworm cotton infestation, added to Arizona’s economic woes that they were just recovering from when economic disaster hit in the form of the Great Depression.

In October 1929, the US stock market crashed, losing around $14 billion in value. The crash helped vault the United States and the World into the worst economic depression we’ve ever known. Many individuals, companies, and even banks had been investing in stocks on the margin – borrowing money with no collateral to buy stocks, which were at an all-time high. When stock values plummeted, they lost everything. Banks failed, companies went bankrupt, and people lost their jobs and their life’s savings. The economies of Europe, already vulnerable in the post-World War I 1920s, also fell into a depression. When some banks closed their doors, people created more trouble by creating runs on banks – trying to withdraw their entire savings, creating bank panics when banks couldn’t immediately provide their money. Farmers in the Midwest, who had already suffered through the recession in the early 1920s, were hit in the 1930s by a combination of poor farming practices and record drought, creating dust storms that ripped hundreds of millions of tons of rich topsoil from their farmlands, leaving nothing useful behind. Governmental policies created to protect American farmers and businesses drove prices up for the US public as other countries levied similar tariffs on US goods in retaliation, cutting America’s revenue from overseas trade by over half. The times were enormously difficult, and it required time and equally enormous creativeness, determination, and ingenuity to pull the country out of the hole in which it found itself.

In October 1929, the US stock market crashed, losing around $14 billion in value. The crash helped vault the United States and the World into the worst economic depression we’ve ever known. Many individuals, companies, and even banks had been investing in stocks on the margin – borrowing money with no collateral to buy stocks, which were at an all-time high. When stock values plummeted, they lost everything. Banks failed, companies went bankrupt, and people lost their jobs and their life’s savings. The economies of Europe, already vulnerable in the post-World War I 1920s, also fell into a depression. When some banks closed their doors, people created more trouble by creating runs on banks – trying to withdraw their entire savings, creating bank panics when banks couldn’t immediately provide their money. Farmers in the Midwest, who had already suffered through the recession in the early 1920s, were hit in the 1930s by a combination of poor farming practices and record drought, creating dust storms that ripped hundreds of millions of tons of rich topsoil from their farmlands, leaving nothing useful behind. Governmental policies created to protect American farmers and businesses drove prices up for the US public as other countries levied similar tariffs on US goods in retaliation, cutting America’s revenue from overseas trade by over half. The times were enormously difficult, and it required time and equally enormous creativeness, determination, and ingenuity to pull the country out of the hole in which it found itself.

–

“The fundamental business of the country…is on a sound and prosperous basis.” – President Hoover, October 25, 1929

“I am convinced we have now passed the worst (of the Depression) and with continued unity of effort we shall rapidly recover.” – President Hoover, May 1, 1930

Hooverville outside of Bakersfield, CA, c1936. Photo by Dorothea Lange, from the Library of Congress.

Despite this positive outlook, six months after the crash the Depression was just getting started in the US, and the early years were the worst. Between 1929 and 1932, over 100,000 businesses went bankrupt, US unemployment reached 24.9%, the average American income was reduced by 40%, and by 1933 over 9,500 banks had failed, taking with them billions of dollars in savings. President Hoover believed in the theory of laissez-faire economics – the idea that the federal government shouldn’t intervene or interfere in business affairs – and that money invested at the top would eventually help those at the bottom. He initially decided to rely on his power of persuasion to help boost the economy after the stock market crash. He asked companies to keep wages up, encouraged the Federal Reserve to make business loans easily obtainable, and suggested the Farm Board provide funds to help stabilize prices of agricultural commodities. The Hoover administration created the Emergency Committee for Employment to help coordinate local welfare agencies (1930); worked with Congress to appropriate $125 million in expanding the lending powers of Federal Land Banks (1931), and created the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (1932) to lend money to banks, trust companies, and insurance companies. Hoover actively worked against and vetoed bigger relief bills with direct federal aid, believing “social assistance” was the responsibility of local officials working with private charities. But states and municipalities were unprepared for the vast effects of the national crisis, which would only get worse.

-

Dorothea Lange - Iconic Images of the Depression

Written by Sarah Matchette, Heritage Square Director of Visitor Engagement

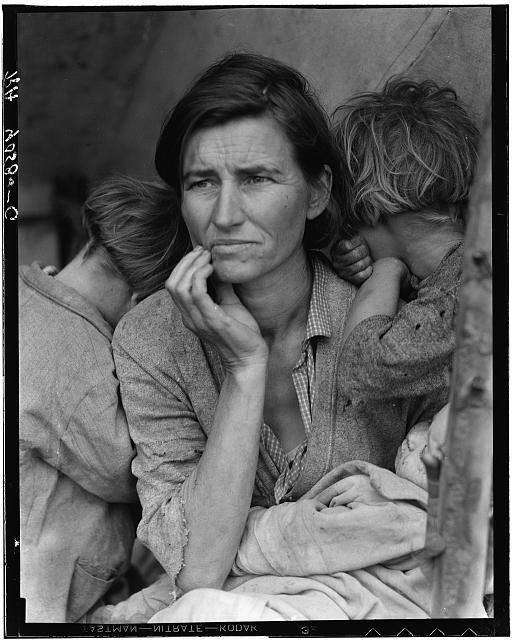

When thinking about the Great Depression, it is hard not to picture “Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California,” a photograph taken in 1936 by Dorothea Lange. This photo is focused tightly on a woman who stares into the distance, anxiety etched onto her face; she is surrounded by three of her children as they hang off her body, their anchor in difficult times.

When thinking about the Great Depression, it is hard not to picture “Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California,” a photograph taken in 1936 by Dorothea Lange. This photo is focused tightly on a woman who stares into the distance, anxiety etched onto her face; she is surrounded by three of her children as they hang off her body, their anchor in difficult times.Dorothea was a trailblazer as a female photographer working in the field during this time. Lange was the first woman to receive a fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation; she also opened her own photography studio in San Francisco in 1919, showcasing her determination and entrepreneurship.

As a photographer, Dorothea Lange saw it as her job to document the world around her and enact change with her artwork. During the Great Depression, Lange worked for the Resettlement Administration and was tasked with photographing the plight of the poor in rural communities. When “Migrant Mother” was published in the newspaper in March of 1936, the State Relief Administration announced that they would send food rations to Nipomo the very next day.

Dorothea remained committed to capturing the truth of people’s daily lives and struggles in her work. During World War II, she photographed Japanese Americans and the loss of their livelihoods and freedom as they were forced into internment camps. She would go on to work for LIFE magazine and travel across the world showcasing the people of Asia, South America, and the Middle East. Lange’s legacy as a documentary photographer is still strong today as her work continues to be featured in museums and in the media. Dorothea’s ability to capture the humanity of different people across the globe and share their stories is truly what makes her an icon of the 20th century.

We have used several Dorothea Lange photographs in our article here, and you can see many more online through the Library of Congress Farm Security Administration Collection, and the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) exhibit – Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures.

–

Migrant family in car along Hwy 70 (1937), Dorothea Lange, courtesy of the New York Public Library.

“Highway 66 is the main migrant road…the path of a people in flight, refugees from dust and shrinking land…” – from The Grapes of Wrath, by John Steinbeck

In 1930, America’s economic problems were exacerbated by an environmental catastrophe in the Midwest – the Dust Bowl. Drought, overgrazing, poor soil conservation methods, removal of native prairie grasses, and high winds combined together to create storms that stripped the land of over a billion metric tons of topsoil and made the land essentially non-arable; sickened and killed crops, livestock, and people; and drove 2.5 million Americans to abandon their homes. Arizona did have drought conditions in the 1930s, but it wasn’t as severe as the drought in the Midwest nor as bad as the drought the state suffered through in the 1890s. The biggest impact the Dust Bowl had on Arizona was that of people – Dust Bowl victims coming to Arizona either moving here purposefully or stopping on their way to find work in California.

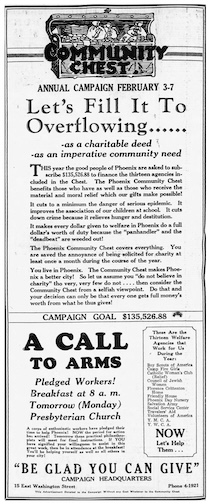

In 1931 a report on the families migrating to and through the state was created, and shared how unprepared Arizona and its municipalities were for such an influx of people. Private charities in six Arizona locations estimated that they saw a 76% increase of people who needed aid in the first six months of 1931, and spent 52% more in aid, as compared to the previous year. Relief sometimes depended on a person’s willingness to work, usually consisted of at least gas and oil to allow people to keep traveling to their intended destination, but also food and healthcare. Aid organizations in Phoenix included the Volunteers of America, the Salvation Army, the Welfare Department of the Catholic Women’s Club, the Travelers Aid Society, Friendly House, and the Social Service Center, as well as many individual businesses and churches. In Phoenix, as in many places around the US, what was called a “Community Chest” (yes, the kind mentioned in the game of Monopoly!) was organized so locals could donate money to people who were struggling.

–

“This nation asks for action, and action now.” – President Roosevelt, March 4, 1933

In November 1932, the US (including Arizona) voted overwhelmingly for Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) and his promises of a New Deal for America over Herbert Hoover and his plan to stay the course. When FDR was inaugurated in March 1933 (Inauguration Day was changed from March 4th to January 20th in 1937), his administration hit the ground running. Two days after he became president, Roosevelt declared a bank holiday – suspending transactions in national banks all over the country from March 6th – 13th to prevent additional bank runs and failures. Arizona had declared a state bank holiday on March 4th after California did so two days earlier. By 1933, Arizona had already lost 19 banks, and state leaders feared that people and companies might create runs on the remaining Arizona banks when they heard of the decision in California. During bank holidays and permanent closures, state governments gave some entities permission to issue their own scrip – certificates used as a substitute for government-issued currency – to facilitate business transactions. Local newspaper accounts mention that the City of Phoenix was looking to issue their own scrip, and that the Arizona Grocery Co. issued scrip as well.

After the banking emergency had been settled, the next thing on FDR’s list was implementing the New Deal, focusing on “the three Rs” – Unemployment Relief, Economic Recovery, and Financial System Reform. During the first 100 days of his Presidency, FDR and Congress passed fifteen major pieces of legislation to help America get back on its feet, and many more in the years to come. Two of the most effective and impactful New Deal bills, in Arizona and nationwide, were the Emergency Conservation Work Act (1933), which created the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), and the Works Progress Administration (WPA).

-

The Livestock Reduction Act

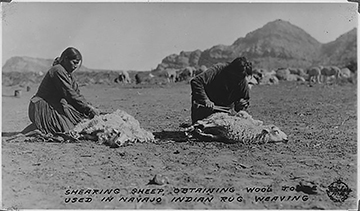

In 1933, the US government passed the Livestock Reduction Act, seeking to control the price of livestock and to conserve areas of the country that were overgrazed, for fear of creating another Dust Bowl. One place they targeted for this reduction was the Navajo Reservation, partially because they erroneously blamed Navajo grazing methods for the buildup of silt in the new Hoover Dam. With little respect for indigenous traditions and livelihood, In the winter of 1933-34 the federal government took close to 200,000 sheep and goats from the Navajo people, paying them pennies on the dollar. Many of the animals were slaughtered immediately because of the government’s inability or unwillingness to move them out of such isolated areas.

In 1933, the US government passed the Livestock Reduction Act, seeking to control the price of livestock and to conserve areas of the country that were overgrazed, for fear of creating another Dust Bowl. One place they targeted for this reduction was the Navajo Reservation, partially because they erroneously blamed Navajo grazing methods for the buildup of silt in the new Hoover Dam. With little respect for indigenous traditions and livelihood, In the winter of 1933-34 the federal government took close to 200,000 sheep and goats from the Navajo people, paying them pennies on the dollar. Many of the animals were slaughtered immediately because of the government’s inability or unwillingness to move them out of such isolated areas.In an interview with Navajo Code Talker Chester Nez, he talks about how his family was “economically and emotionally devastated” when the US government killed 700 of their sheep. In an oral history, Marilyn Help said, “I think my people really got hurt by the livestock reduction program because they are really close to their animals. . . . The government came and took the cattle and the sheep and they just shot them. They threw them into a pit and burned them. They burned the carcasses. Our people cried. My people, they cried. They thought that this act was another Hwééldi, Long Walk.”

Photo: Sheep Shearing, 1933, Bureau of Indian Affairs

From 1933 to 1942, the CCC employed around 3 million men ages 17-25, giving them education, training, shelter, healthcare, money, and food in return for tremendously valuable infrastructure work building roads, dams, forest trails, and buildings; and creating state and national parks, forests, and historic sites. Not to be outdone, the WPA employed over 8.5 million people nationwide, completing 1.4 million projects. Together the CCC and WPA employed tens of thousands of Arizonans, and in 1934 the federal government became the largest employer in Maricopa County. Their projects included much needed infrastructure – they built and/or improved hundreds of miles of roads and highways; improved irrigation infrastructure with new dams, ditches, gutters; built bridges; paved sidewalks; built schools, government buildings, the Arizona Museum of Natural History, etc; improved the Arizona State Fairgrounds (they built a new grandstand, racetrack, and exhibit buildings); built and/or improved parks, playgrounds, and recreational facilities (including South Mountain Park, which also was the site of a CCC work camp).

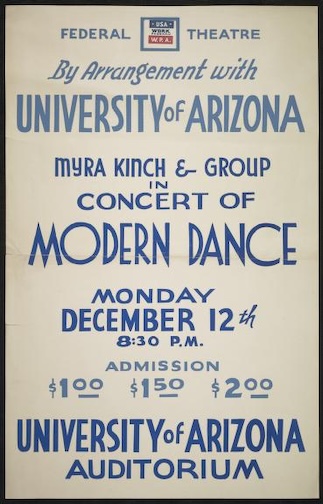

One of the strengths of the WPA was the creation of projects that were called collectively “Federal Project Number One.” They included the Federal Writers’ Project, the Federal Art Project, the Federal Music Project, and the Federal Theatre Project, and employed artists, writers, musicians, actors, and more in their respective fields. Writers created state guidebooks and recorded the life stories of over 10,000 Americans nationwide, actors and other theatre workers staged plays, musicians performed in concerts, and artists created 2,566 murals and 17,744 pieces of sculpture.

One of the strengths of the WPA was the creation of projects that were called collectively “Federal Project Number One.” They included the Federal Writers’ Project, the Federal Art Project, the Federal Music Project, and the Federal Theatre Project, and employed artists, writers, musicians, actors, and more in their respective fields. Writers created state guidebooks and recorded the life stories of over 10,000 Americans nationwide, actors and other theatre workers staged plays, musicians performed in concerts, and artists created 2,566 murals and 17,744 pieces of sculpture.

In addition to infrastructure, there were other meaningful projects initiated by the WPA in Arizona. Funds from the WPA were used to open of schools for adult education, create programs to feed hungry children at Arizona schools, establish a nursery (daycare center) for Black families, provide for creation of community “relief” gardens, set up soup kitchens, and supply library books and other reading materials for migrant families.

–

“…WPA officials this week admitted there was discrimination in the South against colored destitute and unemployed and that whites were given preference in both jobs and relief.” – The Arizona Gleam, December 11, 1936

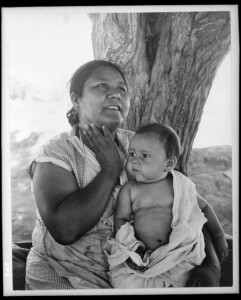

Throughout the course of the Great Depression, people wanted to help local residents before anyone else. A decline in people’s confidence about the present as well as their prospects for the future resulted in rising nationalism, nativism, xenophobia, racism, and isolationism. President Hoover announced support for policy that would reserve American jobs for “real Americans”. He issued strict rules governing who was eligible to emigrate to America, fearing that immigrants would become a burden on the taxpayers and even “steal” employment opportunities. Over a million and a half Mexicans and Mexican Americans were “repatriated” to Mexico during the Depression – sometimes voluntarily, sometimes forcibly, and many through coercive practices from state and local officials. It’s estimated that up to 60% of those “sent back” to Mexico at the time were American citizens. This same effort to keep immigrants out of the US was responsible for the refusal of shelter for mostly Jewish refugees who were fleeing Europe, including the 937 passengers of the St. Louis (1939), and for the difficulty Anne Frank and her family had in trying to obtain immigration visas to the US (1938 and 1941).

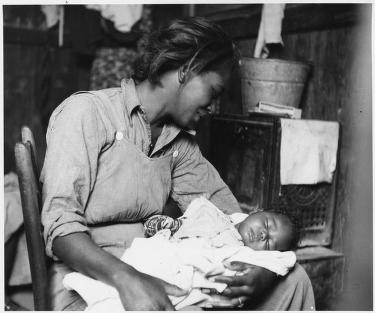

Immigrant mother and child, c1935. Photo by Dorothea Lange, from the Library of Congress.

In a letter to the governor of Arizona, a writer complained that he saw tens of thousands more “aliens” employed than white Americans. In reality much of it was the opposite, with Mexican American and Black American workers being displaced by poor white Americans fleeing the Midwest. Immigrants and minority groups could be discriminated against in New Deal programs because the federal government generally left oversight to state and local governments, where personal prejudices could affect placement on relief rolls, distribution of relief funds, and selection of relief projects. The Arizona Gleam reported that two cities in Texas blocked any Depression relief from being given to Black Americans. And though women’s employment increased during the Depression, most jobs made available to them were confined to those that were traditionally considered “women’s work”, like teaching, nursing, cooking and cleaning.

By 1939, the last “official” year of the Great Depression, unemployment had fallen to 17.2%, the number of bank failures that year was 60 (down from a record high in 1933 of 4,004), and programs like Social Security (1935) and the federal minimum wage (1938) were giving people more economic stability. Investment in New Deal programs certainly helped the country overcome the worst of the Depression, but it didn’t help the US completely overcome its economic woes. For many people and businesses, including Arizona’s agricultural industry, full economic recovery wasn’t a reality until the early 1940s when the US entered the next world war.

–

“Hitler Forbids Jewish Exodus – Reports that numerous Jews were fleeing Germany were followed today by a government announcement that after midnight, no one may leave German soil (without) special permission…” – Arizona Star, April 4, 1933

In the 1930s, the bad news wasn’t all about unemployment, bank failures, and the economy. As the decade progressed, troubling reports from around the world peppered the pages of the newspapers as well as news reports from radio and film. What you would learn about from the news at that time:

- Hitler and the Nazi’s rise to power in Germany – with events like the establishment of the Dachau concentration camp (1933), Kristallnacht (1938), Germany’s annexation of Austria (1938), their partition and takeover of Czechoslovakia (1938-39), and their invasion of Poland (1939) that lead to Great Britain and France declaring war against Germany, officially starting World War II.

- Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia (1935). (Mussolini had come to power in Italy in 1918)

- Japan’s invasion China in 1931 (Manchuria) and the Nanjing Massacre (1937). (They had already seized control of Korea in 1910.)

- Stalin’s political oppression in the Soviet Union (1934-37), called the Great Purge, in which an estimated 10 million people were incarcerated and/or killed to establish strict party-state control and absolute dominance.

- The outbreak of civil war in Spain (1936).

- The signing of cooperative pacts between Germany, Italy, and Japan (1936-1941).

Learn about Depression Era relief gardens (amongst others) from our August 2022 blog, Victory Gardens.

See examples of Depression Era scrip from the State Library of Oregon.

Read diverse life histories from the New Deal Federal Writers’ Project, available from the Library of Congress.

See a list of New Deal projects that were completed in Arizona (there were over 250!), available from the Living New Deal website.

Photographs at the top of the page are of children of migrant laborers at cotton picking camps in Arizona, taken by Dorothea Lange in 1937-38, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Information for this article was found in The National Experience: A History of the United States, 7th edition, 1988; the Library of Congress Chronicling America digital newspaper archive and the Newspapers.com digital archive; Arizona Department of Mineral Resources – History of Mining in Arizona (PDF); US Department of Agriculture – Arizona Agricultural Statistics, 1867-1965 (PDF); Arizona Census of Agriculture, 1940 (PDF); Federal Reserve History – The Great Depression, Bank Holiday of 1933; FDR Presidential Library and Museum – Great Depression Facts, Virtual Tour; WorthPoint – Depression Scrip; JSTOR – When the Banks Closed: Arizona’s Bank Holiday of 1933, Gendered Injustice: Navajo Livestock Reduction…; US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation – Rough Times in the Salt River Valley; The Rogue Columnist – Phoenix in the Thirties; ThoughtCo – Hoovervilles: Homeless Camps of the Great Depression; Salt River Stories – Arizona’s State Fair: The Depression Remade the Fairgrounds; Arizona Memory Project – The Great Depression in Arizona; Commerce in Phoenix, 1870-1942; AZ Public Media – Arizona’s Dust Bowl: Lessons Lost (video); University of Arizona Library – A Brief Report on Transient Families in Arizona, 1931 (PDF); PBS – American Experience: Mass Exodus from the Plains; American Experience: The Works Progress Administration; the Library of Congress – The Dust Bowl, Voices from the Dust Bowl…, Depression and the Struggle for Survival, Works Progress Administration, Navajo Code Talkers; NPR – Survivors of the Great Depression Tell Their Stories, America’s Forgotten History of Mexican-American ‘Repatriation’; National Archives – Family Experiences and New Deal Relief; Farm Credit Administration – History of the FCA; City of Phoenix – History of Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC): South Mountain; The University of Arizona Open-Access Press – Unwanted Mexican Americans in the Great Depression: Repatriation Pressures 1929-1939, by Abraham Hoffman (1974); The Washington Post – The Time a President Deported 1 Million…; History – Underpaid, but Employed: How the Great Depression…; United States Holocaust Memorial Museum – Immigration to the United States, 1933-1941; CNM Open Educational Resources – Indian New Deal & Navajos; and Harvard University – Introduction: Joseph Stalin’s Great Terror.

.

Archive

-

2025

-

January (1)

-

-

2024

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-