Bottoms Up: A History of Prohibition in Arizona

Posted December 1, 2019

Written by Heather Roberts, Research Historian

For a printable, PDF version of this article, please click here.

Did you know…

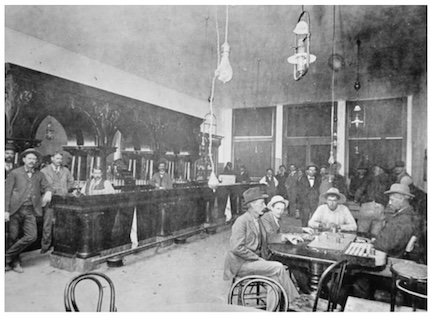

A saloon in Jerome, Arizona, circa 1897.

There has long been a tradition of drinking alcoholic beverages here in Arizona.

Ancient Native Americans here made fermented drinks out of corn (called tiswin), and the fruits of the pitahaya and prickly pear. Spanish missionaries brought grapes, wheat and barley to have tasty food, of course, but also to make wine and beer. German immigrant, Alexander Levin, established the first commercial brewery in Arizona in 1864. And by the early 1880s, the Bagley brothers of Mesa built the first commercial winery in the territory.

When the railroad came to Arizona, trains brought cheaper beer, wine, and spirits to the region. That made things difficult for local brewers, vintners, and distillers, but many were still able to grow and prosper, until disaster struck in the form of a successful ballot initiative in November 1914. Arizonans had voted by a narrow margin to prohibit the sale, manufacture, and consumption of alcohol in the state. It was the thirteenth state to do so, five years before the national ban was enacted. Breweries, wineries, and distilleries had to close. They, as well as bars, restaurants, and stores, had to jettison whatever stock they had left by January 1, 1915.

Some businesses tried to diversify so they could stay open. We know that Billie and Frankie Gammel, who had purchased the Rosson House in August 1914, were already advertising for rooms to rent in a month later. Billie also tried to turn his bar, The Capital Saloon, into a soda shop, which failed. He also attempted ranching, and tried opening a bar in Mexico. It, too, failed. Other businesses, along with the All Saints Catholic Church of Tucson, tried taking the state to court, claiming the new law was unconstitutional, but their application was denied, and in 1916 Arizonans voted to keep prohibition by a 3 to 1 margin. Three years later, Congress passed the Volstead Act over President Wilson’s veto, and Prohibition was enacted nationwide.

Teetotalling was here to stay. So, of course everyone in Arizona and across the country gave up on alcohol and abided by all new state and national laws, drinking only lemonade and iced tea, and boosted the economy by spending their money on their homes and families instead of alcohol. Everyone lived Happily Ever After…

Teetotalling was here to stay. So, of course everyone in Arizona and across the country gave up on alcohol and abided by all new state and national laws, drinking only lemonade and iced tea, and boosted the economy by spending their money on their homes and families instead of alcohol. Everyone lived Happily Ever After…

…

…

Only they didn’t.

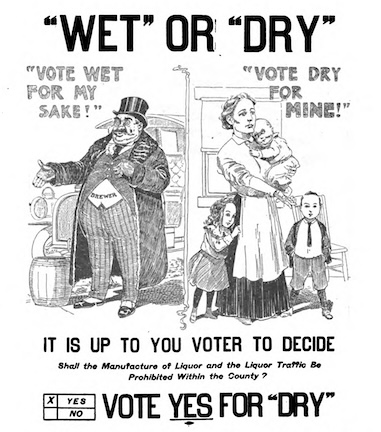

Followers of the temperance movement touted the prohibition of alcohol as the answer to all of society’s ills. Poverty and malnutrition, “familial discord” (otherwise known as domestic violence), robberies, murder and more – they traced it all back to alcohol, and claimed that if alcohol was banned, everything would change for the better. Men would go home and spend time with their families instead of getting drunk at the bar, feeding their “violent tendencies”. They could then spend their hard earned money buying food and clothing for their wives and children, their wives could stay at home and focus on being “good and proper” wives and mothers instead of being “forced” to work outside the home, and everyone could turn over whole trees of new leaves, all due to this “Noble Experiment,” as Prohibition was often called.

But when Prohibition was enacted, however, those things rarely, if ever, happened. People were still people, after all, with all their faults and flaws. And if people didn’t pay their mortgage and rent, treat their families well, or follow laws before Prohibition was passed, they likely wouldn’t do any of that after. As Katherine Morrissey, Associate Professor of History, University of Arizona, said in The Dry Run: Prohibition in Arizona (AZ Public Media), people tended to view Prohibition like we see speed limits today. And, honestly, you’d be pressed to find anyone who hasn’t pushed their car above the posted speed limit, even by a few miles. Except for all of us at Heritage Square, of course. Ahem!

-

Breaking the Law

Who was breaking Prohibition laws? As it turns out, almost everyone.

-

- In October 1915, Billie and Frankie Gammel were fined $300 each for “disposing of intoxicating liquor.” Billie spent 10 days in jail, while Frankie’s jail sentence was deferred.

- Governor Hunt was rumored to have enjoyed a glass of “lemonade” on the Gammels’ front porch.

- Baron Goldwater (owner of Goldwater’s department store, and father of future Arizona conservative, Barry Goldwater), bought his favorite bar when Prohibition was enacted, and moved everything (booze, bar, back bar, and the brass foot rail) to the basement of their house.

- Famous Washington DC bootlegger, George Cassiday, claimed that he sold alcohol to two thirds of the members of Congress.

- Oh, and pretty much everybody in Payson.

-

-

Teetotalling Transportation

“It was as vile a mixture as had ever been concocted.”

“It was as vile a mixture as had ever been concocted.”

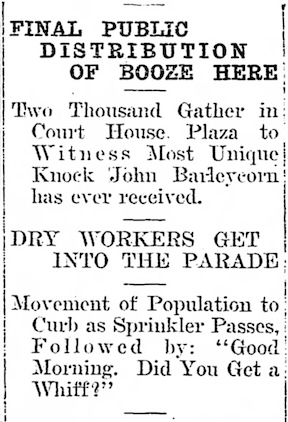

– Arizona Republican, December 30, 1916On Friday, December 29, 1916, close to a mile of the dirt roads in downtown Phoenix were sprayed down with 500 gallons of beer, wine, and liquor, settling the dust and getting at least one bystander thoroughly intoxicated – a bulldog named John Bunyan.

We’re not kidding! This really happened, and was reported on in newspapers here in Arizona as well as across the country – as far away as the territories of Hawaii and Alaska – and even in Canada.

Local authorities had been seizing alcohol from bootleggers since Arizona’s prohibition law went into effect on January 1, 1915. They had destroyed a portion of that booze, but decided at some point to use the remainder to make a political point. The Maricopa County Sheriff’s office used the approximately $10,000 worth of confiscated beer, wine, and liquor, along with 200 gallons of water, to fill a street sprinkler, and had a short parade with the “booze” wagon. Organizers Grady Gammage, B. W. Getsinger, and Dr. H. A. Hughes rode on the wagon while the Phoenix Indian School band played a funeral dirge, and 20 cars filled with temperance promoters joined in. Two thousand people lined the streets to witness the parade, including Waldo Lyon and his bulldog, John Bunyan, who, according to the newspaper account the next day, somehow became overwhelmed by “fumes” after walking very close to the spray. The dog got sick to his stomach and went home to sleep it off, but evidently survived the ordeal – the newspaper reported on his condition later that week in an article that included his photo.

The parade formed at 1st Avenue and Jefferson Street (by the original Maricopa County Courthouse, built in 1884), east on Jefferson to 2nd Street (by the original City Hall, built in 1888), up to Washington Street, west on Washington to 2nd Avenue, and then back to the Courthouse. The crowd – some supporters of Prohibition and some against – kept up with the parade on foot and on bicycle, and gathered some of the resultant “ill-smelling” street sludge in vials to keep as souvenirs of the unique event. But the vials and the newspaper accounts weren’t the only records of the day – several photographers were there, and two motion picture cameras evidently filmed the spectacle, including one operated by local photographer, E. E. Kunselman. The newspaper said the ensuing 125 feet of Kunselman’s film would “be seen in all parts of the country”, though unfortunately we haven’t been able to find any of the footage. Instead, we do have this great picture of the street sprinkler taken by Kunselman (below) – an iconic photo of a truly one-of-a-kind event.

You can read the full article from the December 30, 1916 edition of the Arizona Republican on Chronicling America, or by downloading it in PDF form here – page one and page two.

The Prohibition economy didn’t fare too well, either. Thousands of people lost their livelihoods when breweries, wineries, distilleries, and their associated wholesalers and retail stores went out of business, slashing tax revenues across the country and harming an economy on the brink of the Great Depression. And if people were drinking illegally, they were also spending more money doing so. After Prohibition ended, liquor cost around $4-$7 a gallon; during Prohibition, people spent the same or more on just a fourth of that amount. Prohibition alcohol was also usually of lesser quality, was watered down, and was potentially poisonous.

With so many people breaking the laws and spending much more money on alcohol, not to mention rise of organized crime and the $11 billion in lost tax revenue, it seems a wonder the 18th Amendment wasn’t repealed sooner than 1933. Though talk about changing the constitution went on for years prior, the 21st Amendment, created solely to repeal the 18th, was proposed in February 1933, and ratified on December 5th that same year. In the time between the two dates, Congress also passed a law that allowed beer and wine with 3.2% alcohol content to be sold in states that didn’t have a ban on alcohol. Arizona had repealed their state Prohibition laws in November 1932, and so some intoxicating beverages became legal to sell, ship, and consume when the new beer and wine law went into effect in April 1933.

With so many people breaking the laws and spending much more money on alcohol, not to mention rise of organized crime and the $11 billion in lost tax revenue, it seems a wonder the 18th Amendment wasn’t repealed sooner than 1933. Though talk about changing the constitution went on for years prior, the 21st Amendment, created solely to repeal the 18th, was proposed in February 1933, and ratified on December 5th that same year. In the time between the two dates, Congress also passed a law that allowed beer and wine with 3.2% alcohol content to be sold in states that didn’t have a ban on alcohol. Arizona had repealed their state Prohibition laws in November 1932, and so some intoxicating beverages became legal to sell, ship, and consume when the new beer and wine law went into effect in April 1933.

After the 21st Amendment was passed, the state of Arizona didn’t license anyone to sell liquor in the city of Phoenix until the City Council had new ordinances in place, just in time to celebrate the new year. Huzzah!

Information for today’s blog was gathered from: Sonora: A Description of the Province, Vol. 1, by Father Ignaz Pfefferkorn, 1794; Heritage Square blog, We’re No Angels, Take Two (April 2018); the AZ Wine Growers Assoc. webpage, the Phoenix New Times, Brewing Arizona, the PBS Ken Burns Prohibition series website, the Arizona Republic newspaper archive (November 1932 – December 1933), the Rim County Museum blog, and the AZ Public Media mini-documentary, The Dry Run: Prohibition in Arizona.

Check out The Mob Museum for more cool info about the Prohibition Era, and The Feast Podcast for fantastic episodes that talk about Prohibition, women, and Arizona cocktails.