Victorian Secrets Exhibit

Throughout history, looking at the clothing people wore affords us unparalleled insight into lifestyles that have disappeared. Undergarments – the small clothes worn closest to the body and therefore closest to our lives – are certainly reflections of social, political, and cultural developments.

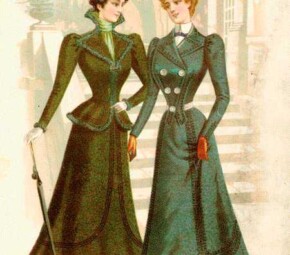

The clothing worn by women, and to some extent men, reached its severest in dictating lifestyle during the 19th century. It was during this period that undergarments gained status as mandatory underpinnings – the very foundation of fashion, modesty, and deportment.

Victorian moral values of the 19th century were reflected in all areas of fashion, but particularly for undergarments, as they were considered the most intimate of apparel. Ironically, it was that very prudery that ultimately projected erotic properties onto underwear. Victorian morals of the 19th Century forbade people in “polite society” from uttering indelicate words, and as a result, undergarments were known as unmentionables rather than by their given terms.

Here are the various “unmentionables” we had on display from September 2013 through July 2015. Click on each image to view it fully.

-

Exhibit Text

The social and moral dictates of the Victorian period required more undergarments than any other period in history, before or after. Victorian ladies wore up to 13 pieces of underwear, weighing between 7 and 10 pounds.

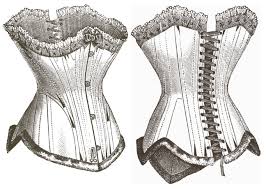

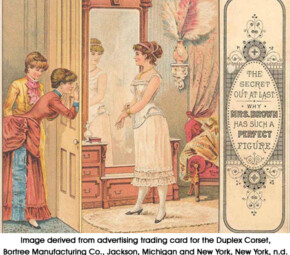

Few garments throughout history have attained as iconic a status as the Victorian corset. But the urge to improve one’s figure with waist stays was not a Victorian development. Corseting was popular in Europe as early as 1500, and it was Puritans in North America that associated being “tightly laced” in undergarments with having good morals.

Corsets for Men:

Corsets are typically associated with women’s fashion, but throughout history, men also have taken to cinching their waists to create a more desirable silhouette. Corsets for men were particularly popular among military men during the Victorian period. This advertisement for men’s corsets was published in Society Magazine, 1899.

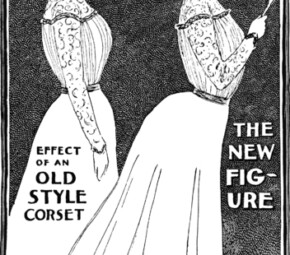

It was female fashion of the 19th Century, however, that took corsetry to new levels of extremism.

Corseting caused great tension both literally and figuratively during the 19th Century. Already considered by her male counterparts as being weak of body and mind, women’s dependence on strict boning, metal stays, and tight lacing perpetuated myths about her ability to function in society.

Corsetry was prized particularly by fashion-conscious, middle-class women because it crafted the flesh into class-appropriate contours. Corsets hid abdominal bulges, smoothed the hips, and created a small, circular waist that supposedly denoted good breeding.

Most corsets sold or made between 1860 and 1910 measured 20 – 22 inches. Those sizes do not account for lacing, which could have been laced out several inches more.

Waist Not:

The extreme corseting often associated with cinching one’s girth down to “hand-span” size was practiced, but not as common as advertisements would lead us to believe. Most women chose to lace-up somewhere in between enhancement and radical transformation.

Still, some women aspired to maintain a waist circumference no larger than the number of years old she was at the time of her marriage.

Maternity Corsets:

Pregnancy offended the Victorian sensibilities that perpetuated an illusion of innocence.

While middle-class Victoriana idealized the image of mother and child, the pregnant body was considered repugnant by polite society. Expecting mothers often wore maternity corsets, which were virtually indistinguishable from standard designs, to conceal their “condition.”

Corsets and Medicine:

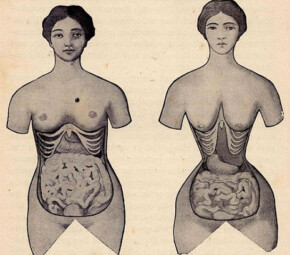

The romance of the tiny waist that held sway over middle-class, Victorian America, was lost on the medical profession. In general, doctors agreed that tight-lacing was detrimental to women’s health. Medical journals published warnings of the health risks associated with long-term corseting. These included uterine damage, punctured lungs, and organ displacement. “Chicken Breast” was a typical ailment among corseted women. The extreme pressure put on the rib cage by metal, boning, and laces caused the ribs to turn inward and overlap the sternum.

Controversy arose within the medical profession, however, when despite warnings, women refused to give up their ideal of the perfect body. This irrational behavior caused doctors to refer back to the weakness of the female mind and its limited capacity for logical thought.

Of Drawers and Drawstrings:

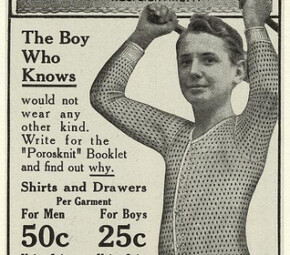

Men’s undergarments through the ages have been marked by simplicity and practicality, particularly in comparison to the complexity of the woman’s underpinnings. Until the 20th Century, the development of men’s under clothing was predominantly unseen, and primarily evolved around the protection and comfort of the genitals.

The Silhouette and the Shape:

Key items in a man’s 19th Century wardrobe included drawers, undershirts, stockings, and garters. Underwear was primarily made of various types of wool until the cotton gin revolutionized the clothing industry. Shape and construction was simple, and few layers were required.

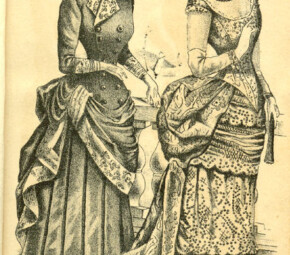

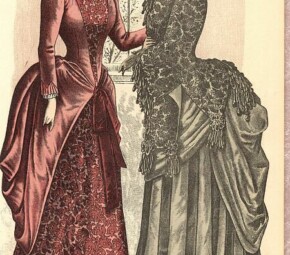

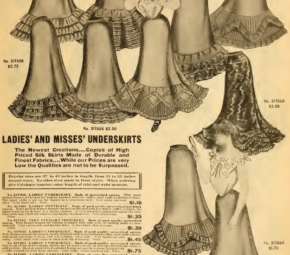

Skirt shapes throughout the 19th century went from one extreme to the other. Yards and yards of skirting in the early 1800s was thought to equal decency and in some cases, women wore up to six petticoats to support their voluminous skirts.

The invention of the crinoline saved women from the weight and bulk of multiple petticoats by providing a rigid framework on which skirt drapery rested.

The onset of the Civil War caused shortages in fabric, and patriotic women were encouraged to pare down. Fullness in skirt drapery was pulled more to the rear and crinolines were given up for simpler bustles.

Bustles were feats of engineering, being both strong enough to support sumptuous displays of fabric and supple enough to allow for graceful movement.

Bustles adopted many forms, from complicated cages to simple, teardrop-shaped pillows tied about the waist.

By 1905, the bustle in all its forms disappeared from women’s fashion. 20th century styles favored a long “S bend” silhouette and a straight skirt. As usual, undergarments followed suit. The new corset featured a dropped waist to elongate the torso and the petticoat was cut on a bias for sleeker draping.

The Chain that Freed Women’s Fashion:

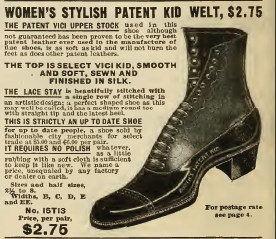

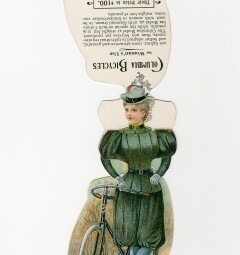

In the 1890s bicycling became popular among American women. The freedom of movement offered by the bicycle proved to be a catalyst for unleashing all manner of reform in the dysfunctional lives of Victorian women. Despite objections from those who thought pedaling too physically demanding and morally suspect, women cyclists took to the streets with fervor.

Phoenicians eagerly embraced the technological wonder of the bicycle, and by 1895 several hundred bicycles were used in town. In contrast to horses, which required constant care, the bicycle was an affordable vehicle that gave ordinary Americans their first taste of independent mobility.

Female cyclists, inhibited by their constrictive clothing and taboos against indecencies like showing their ankles, began pushing the boundaries of propriety with more practical clothing.

Long, voluminous skirts were doffed in favor of bloomers, a move that invoked civil and journalistic contempt. Bloomers were considered mannish and ugly, and invited all manner of criticism from the public. Dress reformers, suffragists, and feminists applauded the move.

“I think [the bicycle] has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world. It gives a woman a feeling of freedom and self-reliance. The moment she takes her seat she knows she can’t get into harm unless she gets off her bicycle, and away she goes, the picture of free, untrammeled womanhood.” – Susan B. Anthony, 1896

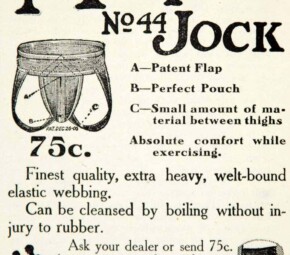

The Bicycle Jockey Strap:

Progression in undergarments due to the popularity of sport wasn’t limited to women. Men’s support also underwent change as a result of adopting more rigorous exercise. In 1874, the Bike Athletic Company began operations in support of bicycle jockeys. To help ease a man’s ride astride the “silent steed,” on the cobbled streets of Boston, Bike originated the “suspensory bandage.” This athletic supporter became known as the bicycle jockey strap – later shortened to “jock strap.”

The Anti-Bloomer Brigade:

“Sensitive young men declare that they cannot tolerate the ‘new woman.’”

A dozen young men of Edmiston, N.Y., have formed what they term the “anti-bloomer brigade,” the prime object of which is opposition to the new bloomer costume now in vogue with female cyclists. Each member of the brigade is required to subscribe to the following pledge: “I hereby agree to refrain from associating with all young ladies who adopt the bloomer cycling costume, and pledge myself to the use of all honorable means to render such costumes unpopular in the community where I reside.” – Cambridge Tribune, August 1895

How many layers did women wear?

Layer 1 – Chemise

A long, sleeveless gown called a chemise was the first layer of clothing. The chemise was a simply-cut, undecorated piece that served as both undergarment and sleepwear. It was worn against the skin under the corset, both to protect the corset from soil and to protect the skin from the lacings and boning of the corset.

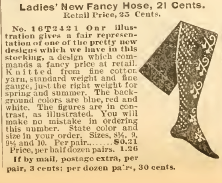

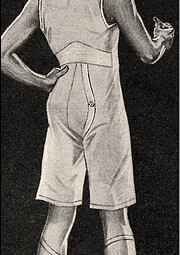

Layer 2 – Drawers

Drawers for women did not become popular until the early 1800s. Prior to that, long, thigh-high stockings and numerous petticoats were sufficient for keeping the legs warm and protected. As crinolines became popular, the danger of sitting down or a strong breeze required covering for modesty. Drawers were loose and made of two leg sections held together with a tie at the waist. When fitted properly, they fell in folds adequate for coverage.

Open drawers were most common, as physicians opposed closed drawers for women, stating, “a free circulation of air by open drawers is wholesome to the parts.” – Kentucky State Medical Society Meeting, May 1892

Layers 2 & 3 – Stockings and Shoes

When dressing, it was critical to put on stockings and shoes early in the process. Once laced into a corset, it was difficult to bend adequately enough to slip into lower undergarments.

Layer 4 – Corset

The corset was worn over the chemise and drawers, and served as a structural garment. While other underclothes were worn for protection, the corset in all its variety of shapes and sizes, was strictly for altering the silhouette to the popular style of the day.

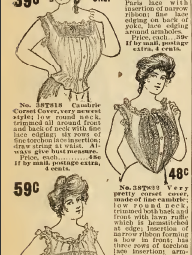

Layer 5 – Corset Cover

Over the corset was worn a corset cover which protected the outer garments from the busk of the corset as well as hid the corset under sheerer garments. Later the corset cover became known as a camisole.

Layer 6 – Petticoat or Underskirt

The petticoat had a dual role as both undergarment and structural piece. It protected the more expensive fabric of the dress, provided warmth, and preserved modesty by hiding the shape of the leg beneath. Petticoats also mirrored the cut of the dress, making it a structural piece that supported the drapery of the skirt.

-

Underwear Fun Facts

- The average American woman owns 21 pair of underwear

- 80% of women are wearing the wrong bra size

- Women wear six different bra sizes throughout life.

- In Italy, women celebrate New Years by wearing red underwear for luck

- A 2008 survey revealed that 9% of men in America have underwear that is at least 10 years old.

- Underwear is a global business with an estimated worth of $30 billion.

- During the Victorian age, women wore knickers, which left the entire crotch area open and exposed because it was believed that an open crotch was more hygienic. Ironically, Parisian Can Can dancers helped usher in closed-crotch drawers (for obvious reasons)

- American women prefer bikini (37%), briefs (23%), thongs (19%), boy shorts (17%), and other (4%). At auction in Edinburgh, pair of Queen Victoria’s underwear sold for £9,375. The expensive undies were made of white cream fabric and had her initials VR (Victoria Regina) embroidered on them.

- King Tut was buried with 145 underpants.

- Some early American settlers had themselves sewn into their underwear for the winter. They did this because it was easier than having to button a lot of buttons. But it also meant that they didn’t bathe until spring.

- 19th century, women wore heavy petticoats to keep the cold breezes from blowing up their skirts because they usually didn’t wear any underwear underneath. Until the mid-1800s, it was considered improper for a woman to wear anything in between her legs. This is why women rode sidesaddle and why pants were considered a male-only garment

- Spiritual undergarments go back at least as far as the ancient Babylonians. Often these garments had fringe, which symbolized of God’s protection.

- Corsets were such a huge business that they provided thousands of jobs. So much whalebone was used to stiffen corsets, hoop skirts and other types of underwear, that the baleen whale was almost driven to extinction.