History Stinks

Did you know…

You can thank the Victorians for making being clean popular again.

By the mid to late 1800s, Louis Pasteur’s germ theory – the idea that germs are everywhere and that they spoil food and cause disease – was proven with the use of microscopes. The idea that germs were prevalent made cleanliness very important to the Victorians. This meant they made every effort to appear and smell clean – from scrubbing their homes with strong carbolic soap, to inventing hot and cold running water to better wash themselves and their belongings. But they also had other ways to keep clean.

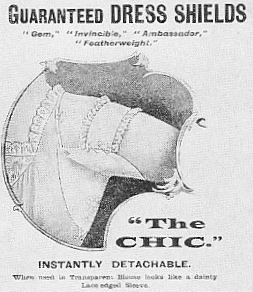

Victorians wore layers of undergarments, not only to give their outer clothing form and shape (think of corsets and bustles), but also to protect them from sweat and dirt from their bodies. With most textile dyes not being colorfast (meaning that washing them with water would make the dye run), along with the fabrics themselves sometimes being delicate enough that water and/or soap would ruin them, Victorian outerwear was often not washed at all – ever! Instead, they would use a clothes brush to remove dust and dirt, spot treat stains when necessary and when possible, and wear underclothes that would absorb sweat and dirt, and that were made of fabrics that could be cleaned on a regular basis. Sometimes “dress shields” (see picture and vintage ad above) were also used – they were removable pads of fabric that were slipped into the armpits of a dress to soak up sweat and odor. Fabric made of cotton and wool were good for this purpose, as both have natural moisture-wicking properties, and wool is naturally anti-microbial (think of your new, “odorless” wool socks!). People who could afford to would also use “dusting powders” (made of starch or talcum) to block or absorb perspiration, and perfumes and scented soaps to disguise any lingering body odors.

Keep in mind, though, that keeping clean was only for people who could afford to do so. Cleanliness was definitely a luxury, as soaps, powders, perfumes, and definitely running water were out of reach for people who were poor. And with the maxim of “Cleanliness is next to godliness,” (John Westley, 1778), people from the lower class were looked down upon because of their inability afford those luxuries, despite working long hours every day for their mere survival.

Learn more about how advertisers influenced Americans ideas about being clean from this Smithsonian Magazine article.